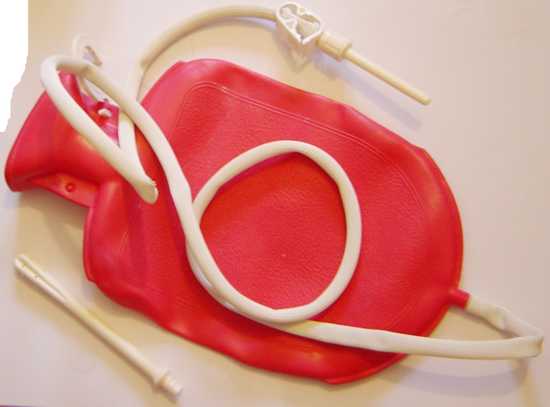

Marcia Munro of Toronto, Canada, underwent a medical procedure involving receiving fecal enemas to treat her intestinal condition. Yes, you read that right. Called a fecal transplant, this peculiar medical procedure is used to treat victims of the intestinal superbug Clostridium difficult. C. difficult, which commonly spreads in hospital environments, can cause chronic diarrhea or colitis, among many other symptoms. When conventional antibiotic treatments fail to eradicate the bug, stool samples from a healthy donor (usually a relative) are obtained and screened for disease like H.I.V. Mixed with saline, the feces is then administered through an enema. The ‘good’ bacteria from the donor feces flourish in the intestines and wipe out the bug in the process. In Munro’s case, stool samples from her sister Wendy Sinukoff were used, transported in an ice-cream container on an airplane traveling to Calgary, where the transplant took place. The hour-long procedure was a success. In fact, studies have shown that over ninety percent of patients treated with fecal transplants were healed – most of them after just one session.

Last 2009, Dr. Elaine Murphy, now Baroness Murphy, admitted into taking part in the creation of ‘cello scrotum,’ a fictional disease that has tricked many British physicians for over thirty years. It all started with a report published in the British Medical Journal in April 1974 by Dr. P. Curtis, describing a phenomenon called ‘guitar nipple,’ a skin condition caused by the soundbox of the guitar pressing against the breasts of female guitar players. Although a legitimate find, Murphy thought the article was a joke, and so, with her husband Dr. J. M. Murphy, decided to ‘ride along’ by writing a reply to the article mentioning a similar condition called ‘cello scrotum,’ this time caused by the body of the cello irritating the scrotum of the patient. Despite the implausibility of the condition (cellos aren’t played so close to the body for the condition to happen), the letter was published. After that, for 34 years, ‘cello scrotum’ was referenced in the BMJ by doctors as a real condition. One scholar even went so far as into debating whether it was contact with the chair, rather than with the instrument, that causes the irritation. It wasn’t until the condition reappeared on the 2008 Christmas edition of the journal that Dr. Murphy decided to come clean, writing another letter to BMJ admitting the fib. Fiona Godlee, editor of the BMJ, has this to say: “It seems the BMJ has been deliciously hoaxed. It is wonderful it has been going all these years and no one realized. We frown on misconduct and medical fraud is taken very seriously. But in this case I hope I am right in saying that no harm has been done.”

Until a successful operation in 2011, Stephen Mabbutt from Oxfordshire, England, suffered from a rare condition that enabled him to listen to his own eyeballs moving around their sockets. The condition, called Superior Canal Dehiscence Syndrome (SCDS), results from the thinning or complete lack of a certain bone in the inner ear, due to the bone eroding, or physical trauma. Symptoms of the disorder include hearing body-generated noises unusually loud in the affected ear, called auto phony, headaches and noise-triggered vertigo (called the Tullio phenomenon). Aside from his eyeballs, during Mabbutt was also reported to hear his own voice, unusually amplified, his joints creaking, his heartbeats, and his stomach churning.

Feng Fujia shocked doctors from Yongkang, Zhejiang Province, China, who discovered that his breathing problems were caused by a tooth growing inside his nostril. “Recently the problem gets worse and worse, and my nose is so smelly that my co-workers all stay away from me,” commented Fujia, who had been suffering from breathing difficulties for the past five years. Desperate for a cure, the 21-year old finally went to a hospital for treatment, and eventually the misplaced tooth was removed. Doctors explained that the tooth probably got there during what they call Fujia’s ‘early dental transitional period,’ when he ate something so hard that it pushed an upper tooth into his nasal cavity. “It’s like pushing a tree seed into another place and after a long time the seed started to sprout and grow out. As teeth grow very slowly, it only could be discovered years later that it sprouted in the nostril,” said Fejia’s doctors.

Twinkle Dwivedi, a schoolgirl from Lucknow, India, became the subject of various medical studies and TV shows around the world due to her bizarre condition. Since she was 12 years old, she began to bleed spontaneously through her skin on any part of the body, sometimes up to 20 times a day, without feeling any pain or sustaining any visible wounds. ‘It was scary and messy. My school blouse went all red. No-one would come near me or play with me,’ said Twinkle of her ailment. Various theories were proposed on what could cause her predicament, like Type II von Willebrand disease (a clotting disorder) or hematohidrosis (where the patient sweats blood through her skin), but despite efforts by various experts, they remained baffled by the nature of her disease.

Lichtenburg figures are branching fractal patterns caused by electric discharges, such as lightning, hitting the surface of insulating materials. Named after German physicist Georg Christoph Lichtenberg, the figures, while commonly observed in lightning-struck objects, are also seen to appear, albeit rarely, on the skin of lightning-strike survivors. The skin patterns, called ‘lightning flowers,’ are reddish in color, and can last for several hours, or even days, before it disappears completely. The cause of the markings is not yet fully explained. It is suggested that capillaries rupturing under the skin due to the lightning current passing through causes the ‘flower,’ while others say that the patterns are actually bruises caused by the shock waves from the lightning strike. What’s more puzzling, however, is how people exhibiting these ‘flowers’ managed to survive a lightning strike in the first place, with little to no injuries.

In December 8, 2009, a medical team led by Dr. Ashish Rawandale-Patil from the Institute of Urology in Dhule, India, performed a four-hour long operation to remove an astounding 172,155 kidney stones from the left kidney of Dhranraj Wadile. 45-year old Wadile, who was enduring acute pain for more than six months, consulted with many physicians before he was diagnosed with a rare birth defect called pelvi-ureteric junction obstruction, meaning his kidney was positioned abnormally around the pelvic area of his body. Wadile was then immediately whisked to surgery to address his ailment. The unprecedented number of stones complicated the surgery, with the stones varying in size from a millimeter to 2.5 centimeters. The counting of the stones, which were composed of calcium oxalate and calcium phosphate, was laborious as well, taking three hours daily for over a month to finish.

Nguyen Thi Phuong, a young woman in her late 20s, from a province in Mekong Delta, Vietnam, suffered from a yet-to-be-diagnosed disorder that left her with wrinkled, saggy skin all over her body, giving her the appearance of a seventy year-old. The condition began in 2008, when Phuong decided to self-medicate following a rather severe allergic reaction from eating seafood. After pharmacy drugs stopped the itching but didn’t remove her hives, she resorted to traditional medicine. The hives disappeared, but her skin began ‘aging’ overnight. “The skin on my face, chest and belly has folds like an old woman who has given birth several times although I have never had a child. But the rapid-aging syndrome hasn’t affected my menstrual cycle, hair, teeth, eyes and mind,” said Phuong. The condition got so severe that Phuong was forced to wear a mask in public. Theories about what could cause Phuong’s wrinkled skin include overuse of medication containing corticosteroids, which can cause a condition called Cushing’s Syndrome, which features thinning of the skin and weight gain, and lipodystrophy, an incurable syndrome that causes fat layers in the skin to disintegrate, while the skin itself starts growing faster than usual – but doctors have yet to find a final diagnosis.

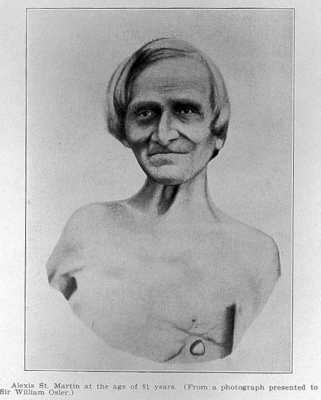

On June 6, 1822, in a fur trading post on Mackinac Island, a 20-year old voyageur named Alexis St. Martin, was accidentally shot at close range by a musket. Dr. William Beaumont, a US Army surgeon, quickly come to his aid and attempted to treat St. Martin, whose accident damaged his ribs and left him with a gaping wound in his abdomen. While his prognosis on St. Martin’s condition was grim, Beaumont continued to treat the wound. For the succeeding 17 days, the food that St. Martin ate began pouring out of the wound, until the 18th day, when the food began staying inside his stomach. The wound healed, but a hole called a fistula formed on St. Martin’s stomach. Since there was little understanding of the digestion process back then, Beaumont, realizing the scientific opportunity, began experimenting on St. Martin on and off for 11 years. After the treatment, Beaumont made the illiterate St. Martin sign a contract making him work as a servant for him. St. Martin, who kept working despite his fistula, allowed Beaumont to dangle various pieces of food into his fistula, recording their individual rates of digestion, as well as obtaining vials of gastric juices straight from his stomach. During the course of the experiments, Beaumont discovered lots of facts about the process of digestion, most notable being the role of stomach acid in the digestion process, which indicates that digestion is not merely a mechanical process, but a chemical one. Beaumont’s findings were eventually published in 1838 in “Experiments and Observations on the Gastric Juice, and the Physiology of Digestion” and he became known as the ‘Father of Gastric Physiology.’ As for St. Martin, he and Beaumont decided to part ways after the experiments, with St. Martin returning to his home in Quebec and Beaumont settling in St. Louis, Missouri.

David Phillip Vetter, a young boy from Texas, was born with a genetic disease called severe combined immune deficiency syndrome (SCID), which forced him to live almost his entire life in a sterilized, bubble-shaped cocoon at the Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston, to ‘isolate’ him from germs and viruses. His condition, which made him extra-susceptible to diseases, made him famous in the media, who gave him the moniker ‘the boy in the plastic bubble.’ His parents, David Joseph, Jr. and Carol Vetter, already had a daughter, but also lost a son due to SCID, yet despite warnings from doctors about a 50% chance of them bearing another son with SCID, they decided to have a third pregnancy. Upon Vetter’s birth in September 21, 1971, he was immediately isolated in his plastic sterile cocoon. Due to his delicate condition, every item entering his cocoon were heated 140 degrees in an ethylene-oxide chamber, and any contact with him should be made only through special gloves attached to the walls of his cocoon. Although the inflating system inside the bubble made communication difficult, David’s family tried their best to give him a ‘normal’ life. He was baptized inside the bubble using sterilized holy water, he was given a formal education and a playroom and television set was even provided. Eventually, a separate bubble chamber was built for him in his home, along with a transport bubble so that David can spend some time at home with his family. In 1977, NASA even designed a special spacesuit (still attached to the chamber via a tube) for David to wear so he can finally get out of his cocoon, although he used the suit only a total of seven times. Eventually, the medical team in charge of Vetter, who already sank 1.3 million dollars for his care, decided to do a bone marrow transplant despite not yet finding an exact match for him due to concerns about Vetter being volatile and unruly as he enters adolescence. The transplant went well, that is, until Vetter suddenly become so severely ill that he was taken out of the cocoon for treatment. Unfortunately, fifteen days after the transplant, Vetter died at the age of 12 on February 22, 1984 due to Burkitt’s lymphoma, which arose from a previously undetected trace of the Epstein-Barr virus in the bone marrow his sister donated to him. Vetter’s tragic life and death managed to bring up many ethical issues about the viability of the ‘isolation’ treatment in treating SCID patients, especially its psychological impact on children. Fortunately, advances in medicine over the years have rendered the ‘isolation’ treatment obsolete.