SEE ALSO: 10 Of Human History’s Most Atrocious Plagues

The first signs of plague in Moscow appeared in late 1770, which would turn into a major epidemic in the spring of 1771. The measures undertaken by the authorities, such as creation of forced quarantines, destruction of contaminated property without compensation or control, closing of public baths, etc., caused fear and anger among the citizens. The city’s economy was mostly paralyzed because many factories, markets, stores, and administrative buildings had been closed down. All of this was followed by acute food shortages, causing deterioration of living conditions for the majority of the Muscovites. Dvoryane (Russian nobility) and well-off city dwellers left Moscow due to the plague outbreak. On the morning of September 17, 1771, around 1,000 people gathered at the Spasskiye gates again, demanding the release of captured rebels and elimination of quarantines. The army managed to disperse the crowd yet again and finally suppressed the riot. Some 300 people were brought to trial. A government commission headed by Grigory Orlov was sent to Moscow on September 26 to restore order. It took some measures against the plague and provided citizens with work and food, which would finally pacify the people of Moscow.

The Great Plague of Marseille was one of the most significant European outbreaks of bubonic plague in the early 18th century. Arriving in Marseille, France in 1720, the disease killed 100,000 people in the city and the surrounding provinces. However, Marseille recovered quickly from the plague outbreak. Economic activity took only a few years to recover, as trade expanded to the West Indies and Latin America. By 1765, the growing population was back at its pre-1720 level. This epidemic was not a recurrence of the European Black Death, the devastating episodes of bubonic plague which began in the fourteenth century. Attempts to stop the spread of plague included an Act of Parliament of Aix that levied the death penalty for any communication between Marseille and the rest of Provence. To enforce this separation, a plague wall, the Mur de la Peste, was erected across the countryside (pictured above).

The Antonine Plague (also known as the Plague of Galen, who described it), was an ancient pandemic, of either smallpox or measles, brought back to the Roman Empire by troops returning from campaigns in the Near East. The epidemic claimed the lives of two Roman emperors — Lucius Verus, who died in 169, and his co-regent who ruled until 180, Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, whose family name, Antoninus, was given to the epidemic. The disease broke out again nine years later, according to the Roman historian Dio Cassius, and caused up to 2,000 deaths a day at Rome, one quarter of those infected. Total deaths have been estimated at five million. The disease killed as much as one-third of the population in some areas, and decimated the Roman army. The epidemic had drastic social and political effects throughout the Roman Empire, particularly in literature and art. (Pictured above is a plague pit containing the remains of people who died in the Antonine Plague.)

The Plague of Athens was a devastating epidemic which hit the city-state of Athens in ancient Greece during the second year of the Peloponnesian War (430 BC), when an Athenian victory still seemed within reach. It is believed to have entered Athens through Piraeus, the city’s port and sole source of food and supplies. The city-state of Sparta, and much of the eastern Mediterranean, was also struck by the disease. The plague returned twice more, in 429 BC and in the winter of 427/6 BC. Modern historians disagree on whether the plague was a critical factor in the loss of the war. However, it is generally agreed that the loss of this war may have paved the way for the success of the Macedonians and, ultimately, the Romans. The disease has traditionally been considered an outbreak of the bubonic plague in its many forms, but re-considerations of the reported symptoms and epidemiology have led scholars to advance alternative explanations. These include typhus, smallpox, measles, and toxic shock syndrome.

The Italian Plague of 1629-1631 was a series of outbreaks of bubonic plague which occurred from 1629 through 1631 in northern Italy. This epidemic, often referred to as Great Plague of Milan, claimed the lives of approximately 280,000 people, with the cities of Lombardy and Venice experiencing particularly high death rates. This episode is considered one of the last outbreaks of the centuries-long pandemic of bubonic plague which began with the Black Death. German and French troops carried the plague to the city of Mantua in 1629, as a result of troop movements associated with the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648). Venetian troops infected with the disease retreated into northern and central Italy, spreading the infection. Overall, Milan suffered approximately 60,000 fatalities out of a total population of 130,000. SEE ALSO:10 Twisted Facts About The Dancing Plagues

Before the European arrival, the Americas had been largely isolated from the Eurasian–African landmass. First large-scale contacts between Europeans and native people of the American continents brought overwhelming pandemics of measles and smallpox, as well as other Eurasian diseases. These diseases spread rapidly among native peoples, often ahead of actual contact with Europeans, and led to a drastic drop in population and the collapse of native American cultures. Smallpox and other diseases invaded and crippled the Aztec and Inca civilizations in Central and South America in the 16th century. This disease, with loss of population and death of military and social leaders, contributed to the downfall of both American empires and the subjugation of American peoples to Europeans. Diseases, however, passed in both directions; syphilis was carried back from the Americas and swept through the European population, decimating large numbers.

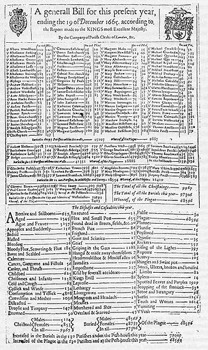

The Great Plague (1665-1666) was a massive outbreak of disease in England that killed 75,000 to 100,000 people, up to a fifth of London’s population. The disease was historically identified as bubonic plague, an infection by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, transmitted through fleas. The 1665-1666 epidemic was on a far smaller scale than the earlier “Black Death” pandemic, a virulent outbreak of disease in Europe between 1347 and 1353. The Bubonic Plague was only remembered afterwards as the “great” plague because it was one of the last widespread outbreaks in England. Although the disease causing the epidemic has historically been identified as bubonic plague and its variants, no direct evidence of plague has ever been uncovered. Some modern scholars suggest that the symptoms and incubation period indicate that the causal agent may have been a disease similar to a viral hemorrhagic fever. (Pictured above is a list of mortalities from the time of the plague.) The Plague of Justinian was a pandemic that afflicted the Byzantine Empire, including its capital Constantinople, in the years 541–542 AD. The most commonly accepted cause of the pandemic is bubonic plague, which later became infamous for either causing or contributing to the Black Death of the 14th century. Its social and cultural impact is comparable to that of the Black Death. In the views of 6th century Western historians, it was nearly worldwide in scope, striking central and south Asia, North Africa and Arabia, and Europe as far north as Denmark and as far west as Ireland. The plague would return with each generation throughout the Mediterranean basin until about 750. The plague would also have a major impact on the future course of European history. Modern historians named it after the Eastern Roman Emperor Justinian I, who was in power at the time and himself contracted the disease. Modern scholars believe that the plague killed up to 5,000 people per day in Constantinople at the peak of the pandemic. It ultimately killed perhaps 40 percent of the city’s inhabitants. The initial plague went on to destroy up to a quarter of the human population of the eastern Mediterranean. Watch this video on YouTube

The “Third Pandemic” is the name given to a major plague pandemic that began in the Yunnan province (pictured above) in China in 1855. This episode of bubonic plague spread to all inhabited continents, and ultimately killed more than 12 million people in India and China alone. According to the World Health Organization, the pandemic was considered active until 1959, when worldwide casualties dropped to 200 per year. The bubonic plague was endemic in populations of infected ground rodents in central Asia, and was a known cause of death among migrant and established human populations in that region for centuries; however, an influx of new people due to political conflicts and global trade led to the distribution of this disease throughout the world. New research suggests Black Death is lying dormant.

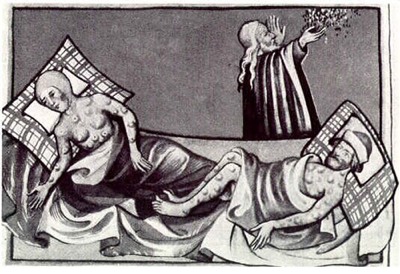

The Black Death (also known as The Black Plague or Bubonic Plague), was one of the deadliest pandemics in human history, widely thought to have been caused by a bacterium named Yersinia pestis (Plague), but recently attributed by some to other diseases. The origins of the plague are disputed among scholars. Some historians believe the pandemic began in China or Central Asia in the late 1320s or 1330s, and during the next years merchants and soldiers carried it over the caravan routes until in 1346 it reached the Crimea in southern Russia. Other scholars believe the plague was endemic in southern Russia. In either case, from Crimea the plague spread to Western Europe and North Africa during the 1340s. The total number of deaths worldwide is estimated at 75 million people, approximately 25 to 50 million of which occurred in Europe. The plague is thought to have returned every generation with varying virulence and mortalities until the 1700s. During this period, more than 100 plague epidemics swept across Europe. (This article is licensed under the GFDL because it contains quotations from Wikipedia.) SEE ALSO: 8 Fascinating Facts About Plague Doctors Read More: Facebook Instagram Email