With its famous past as a penal colony, the Australia of old was not for the faint of heart. Bushrangers and con men alike ravaged the continent, committing unspeakable acts. The following list examines ten seemingly forgotten 19th-century massacres and mass murders that riveted both the headlines of Australia as well as the world stage.

10 The Baby-Farming Murderer

While tending to a communal garden in Moreland Rd, Coburg, a man unearthed the lifeless remains of a baby girl. Following a police investigation, a second child’s body was discovered, with tape tightly wound around the boy’s neck. The atrocity of the sickening crime ultimately led police to Frances Lydia Alice Knorr, a 23-year-old English migrant working as a domestic servant. Baby farming, as it was known, was a common occupation where working-class women were hired to care for so-called “illegitimate children.” Much public opposition arose subsequent to Knorr’s trial and death sentence, particularly from women and church groups. The escalating, emotion-charged outpouring of sympathy became an immense burden for the executioner, Thomas Jones, who felt pressure and disdain from both the public and his wife. Two days before Jones was to meet Knorr at the gallows, the hangman slit his own throat. Nevertheless, Jones was replaced by a man named Roberts, who saw to it that Knorr would hang in the early hours of January 15, 1894. In spite of Knorr’s incessant claims of innocence, authorities discovered a penned confession in her cell following her execution that read, “I express a strong desire that this statement be made public, with the hope that my fate will not only be a warning to others but also act as a deterrent to those who are perhaps carrying on the same practice.” Further inquiries later revealed that Knorr was responsible for more than a dozen other infants’ deaths.[1]

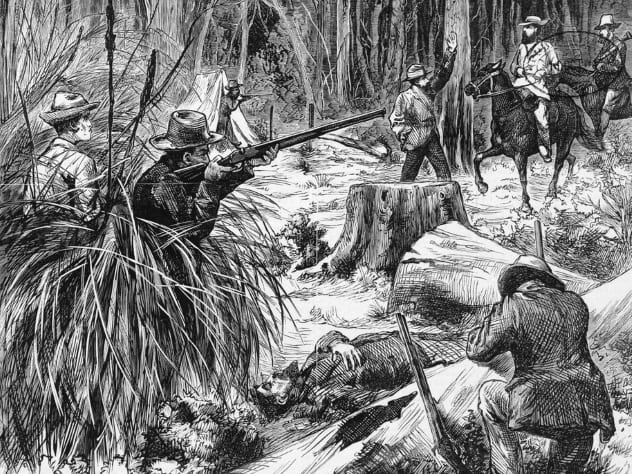

9 Stringybark Creek Massacre

In October 1878, the Kelly Gang was on the run, hiding out in the wild bushlands of Northeast Victoria. With their whereabouts narrowed down, four officers were dispatched to apprehend the murderous outlaws, eventually setting up camp at Stringybark Creek. Unbeknownst to them, the Kelly Gang was well aware of their location, patiently waiting in the brush for an opportune moment to execute their ambush. In a profound lapse of judgment, Sergeant Kennedy and Constable Scanlan left the camp at dawn to search for the gang, leaving their partners, Lonigan and McIntyre, behind, vulnerable and outnumbered. The Kelly Gang ambushed the camp in the late afternoon, whereupon they immediately executed Lonigan. Over the next several hours, McIntyre was held at gunpoint, knowing full well the fate that awaited his unsuspecting comrades. Upon their return, a barrage of gunfire erupted. While Constable Scanlan’s mortally wounded body fell to the ground, a weaponless McIntyre leaped onto a horse that had bolted in the onslaught, leaving a doomed Kennedy in the dust. Public outrage to the triple murder was swift and tremendous, with the State of Victoria officially declaring the Kelly Gang as outlaws; thus, it was legal to shoot and kill Ned Kelly, Dan Kelly, Joe Byrne, and Steve Hart on sight without an attempted arrest.[2] Surprisingly, the gang would go on to live another two years despite overwhelming odds mobilized against them. In the years that followed, locals began flocking to Stringybark Creek to observe a morbid piece of Australian history.

8 Joseph Thyer

It was a Monday afternoon, October 12, 1896, when 17-year-old George Albert Thyer returned to the family farm after spending the weekend away. Immediately upon his arrival, George noticed something hanging in the stockyard a mere 91 meters (300 ft) from the entrance of his home. It was the body of his father, 44-year-old Joseph Thyer. Frantic and distraught, George ran inside the house, only to find the bloody and disfigured bodies of his mother and younger siblings—36-year-old Elizabeth, Florence (12), Edward (9), Alexander (7), Charlie (6), and Roy (4 months)—their skulls split open with an unknown blunt weapon. Three of the victims were struck multiple times with such a force that the top parts of their skulls were entirely removed. Joseph Thyer had killed them all before hanging himself. It would be another two days until their corpses were removed from the gruesome scene. In the three blistering days that elapsed, the “strongest disinfectants” were required by the undertaker in an attempt to lessen the haunting and repulsive stench of death and decay. Settlers in neighboring localities were beside themselves after hearing the news of such butchery at the hands of Mr. Thyer, a well-known, reserved, and highly respected man in Cavanagh, SA. In spite of his perceived character, Joseph Thyer had a violent temper and had been complaining of “pains in his head” in the weeks leading up to the murders. On October 14, Elizabeth and Florence were placed in a casket, while the four boys were put into two separate caskets, two boys per coffin. The four caskets were then lowered into the ground, together in one grave.[3] Fittingly, the body of the craven savage who snuffed out their lives was buried alone in a separate plot.

7 Glover Family Tragedy

With the nation still reeling from the Thyer family murder, a similar act of unspeakable violence would shock the quiet little community of Triabunna in 1898. On the first day of March, watchhouse-keeper George Glover was notified by his eldest daughter that his wife, Mary Catherine, and their six younger children were missing. Over the next several hours, local businesses suspended operations, with every man in town volunteering to form a search party. Before dusk that evening, the town’s worst nightmare had come to fruition. Combing through the brush with his trusted spaniel, storekeeper Edward Ford found the bodies of the six youths—ages ranging from four months to 11 years—lying together, covered in bloodied blankets and shawls.[4] Their throats had been slit from ear to ear, and based on appearances, it was theorized that the children had been sleeping or were drugged at the time of their murder. Upon news of the slayings, great anxiety overtook the town, not due to Mrs. Glover’s well-being but to her unknown whereabouts. She had been described as a peculiar woman with a history of depression, and locals worried that Mary was eluding capture with the intention of murdering her two eldest daughters. Such speculations, however, would be rendered forever moot upon the discovery of her body more than 1.6 kilometers (1 mi) outside of town. Lying facedown in shallow water not more than 0.6 meters (2 ft) deep, it appeared that Mary had attempted, but failed, to cut her own throat prior to drowning. All that remained for detectives, in the end, was rolled up cash in Mary’s pockets, the murder weapon stained in children’s blood, and an eternity of unanswered questions.

6 Thomas Jeffries

On December 31, 1825, Thomas Jeffries broke out of the Launceston Watch House in Van Diemen’s Land (present-day Tasmania). He was accompanied by fellow jailbirds John Perry, James Hopkins, and a man identified only as “Russel.” That evening, the four men broke into the residence of a respected settler named Tibbs, who, along with his wife and male servant, soon found themselves being tied up by the infernal intruders. In that moment, a struggle ensued, and shots were fired. As the two innocent men’s bullet-riddled bodies lay lifeless on the ground, Mrs. Tibbs and her infant son were led to the forest in the dark of night. In the seclusion of the woodlands, Jeffries forcefully snatched the five-month-old from his mother’s shielding arms and bashed the baby to death against a tree. The dreadful degree of the true horrors of that evening became apparent among the locals a week later, when the infant’s battered and decayed remains were discovered. What was left of the baby was nothing more than mangled flesh and bone, torn apart by the carnivorous animals of the terrain. During this time, Jeffries and his partners remained at large, with the exception of Russel, who was shot and partly eaten by the others. Jeffries and Perry would be captured a few days later after the murder of Magnus Bakie, for which they stood trial. During court testimony, Mrs. Tibbs—who was raped and left to die in the woods—collapsed upon seeing her child’s killers. On May 4, 1826, Jeffries and Perry were led to the gallows and hanged.[5]

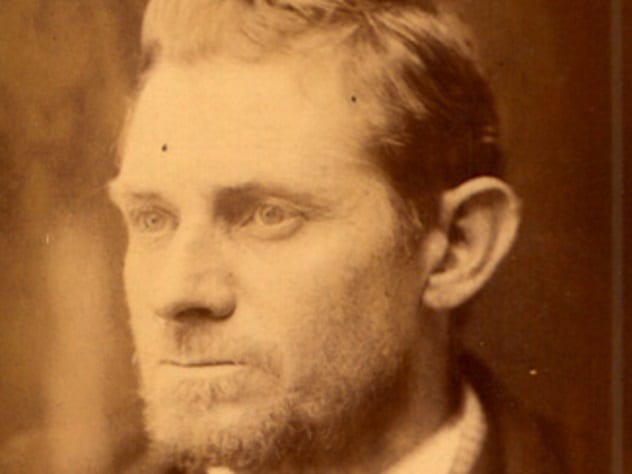

5 Frederick Bailey Deeming

Conman and murderer Frederick Bailey Deeming had already spent the majority of his life in and out of prison by the time he married Marie James in England in 1881. Having four children with Marie did not stop Deeming’s bigamist heart from marrying Helen Matheson in 1890. As if juggling two families wasn’t enough, Mr. Lady-Killer (no pun intended) added another notch to his blissful union belt in September 1891 to Emily Lydia Mather. Three months later, the newlyweds moved to Windsor, Australia, where they rented a brick cottage which still stands at 57 Andrew Street. A little over a week later, on Christmas Day, the ever-so-charming philanderer bludgeoned Emily, slit her throat, and then buried her naked body beneath the hearthstone of their bedroom. The following month, the cold-blooded killer sailed to Sydney, where he immediately became engaged to Kate Rounsefell. Fortunately for his newfound love interest, their whirlwind romance would be short-lived. Due to a putrid smell emitting from the floorboards of the Windsor cottage, Emily’s decomposing remains were discovered, leading to Deeming’s arrest in Western Australia. When the news made its way to England, Emily’s grieving mother recalled floor work her murderous son-in-law had done at his former home in Rainhill. Due to this, local authorities excavated the floors of the couple’s previous residence, only to discover Deeming’s first wife Marie and their four young children entombed in concrete.[6] The savagery of the crimes became a media spectacle, with the press accusing Deeming of being Jack the Ripper. Overnight, newspapers nationwide labeled him “The Jack the Ripper of the Southern Seas.” In all the time during his trial, he never once confessed to or denied being the Ripper, possibly due to the fact that he undoubtedly relished the fame. On May 23, 1892, Deeming enjoyed one last cigar as he walked to the gallows in front of a crowd of 12,000 enthusiastic spectators.

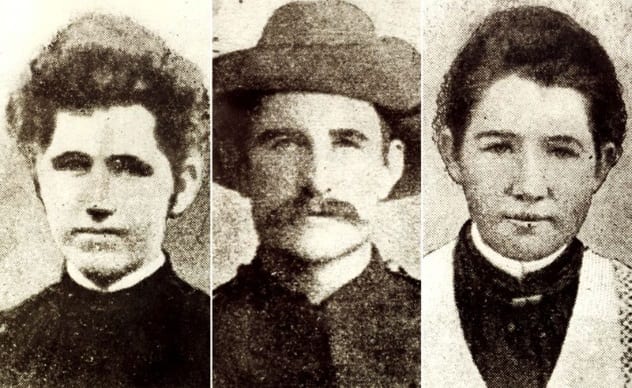

4 The Gatton Murders

On the night of December 26, 1898, Michael Murphy, 29, and his sisters Norah, 27, and Theresa “Ellen,” 19, made their way to a dance in the small town of Gatton. The following morning, the three had yet to return to the Murphy farm, prompting a search that would lead to their grisly discovery in a secluded pasture. Lying neatly beside one another with their feet pointing to the west, it appeared that the siblings’ blood-soaked corpses were posed by their killer. While ants crawled across their lifeless bodies, investigators noted that the girls’ hands had been bound and that they had possibly been raped with the brass-mounted handle of a riding whip. Furthermore, all three were bludgeoned to such an extent that Norah’s brains masked her face. The callous killer didn’t even bother to spare the Murphys’ horse, which was found shot in the head a few yards away. The subsequent investigation by authorities was the epitome of incompetence, given the myriad of illogical mistakes. Case in point, it took two days for investigators from Brisbane to arrive at the scene of the crime, and by that time, curious locals had unreservedly contaminated the crime scene. Throughout years of speculation, one man has been singled out as the likely culprit: Thomas Day, a local butcher who was seen lurking near the crime scene on the night of the murders. Weeks prior to the Murphy slayings, Day was suspected in the killing of 15-year-old Alfred Stephen Hill, whose pony was also found with a single bullet to the head. In 1900, Day shot himself in the head and died in the Sydney Hospital. More than a century later, the Gatton murders remain unsolved.[7]

3 Cape Grim Massacre

In the early 1800s, the majority of the Aboriginal people of Northwestern Tasmania were hunted down and slaughtered in an attempted genocide led by VDL Company hunting expeditions. According to the company’s chief agent, Robert Curr, “We have to lament that our own countrymen consider the massacre of these people an honour.” By December 1827, complacency among the Aboriginal people had ceased, and reprisal attacks, something seldom seen before, were escalating. Following the murder of numerous Aboriginal men who died protecting their women from rape, the natives exacted their revenge by driving over 100 sheep belonging to the company off a cliff. This led to a “company punitive expedition” in 1828, resulting in the butchery of 12 Aboriginals following a sneak attack. The bloodshed only worsened in the days that followed, when the same party of murderous shepherds encountered another group of Aboriginal people. On that day, February 10, around 30 terrified natives were systematically massacred before their bodies were thrown off the 60-meter (200 ft) cliff in what is now remembered as the Cape Grim Massacre. Such appalling brutality continued in the years to come, with the lieutenant governor declaring martial law, which permitted the capture or murder of Aboriginal people. By 1830, an estimated 60 Aboriginals of the northwest tribe remained.[8]

2 The Maria Shipwreck Massacre

One of the most controversial events in Australian maritime history began on June 26, 1840, when 26 souls left Port Adelaide on the brigantine Maria. The vessel was bound for Hobart under Captain William Smith. However, it foundered for unknown reasons off the coast of Kingston. With fading hope for Maria’s anticipated arrival, reports began circulating that all aboard were murdered by natives after “a massacre site” was discovered along the coastline. This spawned a party of men to investigate, all of whom described finding “legs, arms and parts of bodies partially covered with sand and strewn in all directions.” Wedding rings found on the slain bodies of two female passengers were recovered in addition to the men describing how they had witnessed a native wearing a sailor’s jacket. As the public’s ire progressively escalated, Governor George Gawler instructed Major Thomas O’Halloran to lead a team on horseback and perpetrate retribution upon those responsible. Specifically, once identifying those he believed to be the culprits, Major O’Halloran was ordered to serenely “explain to the blacks the nature of your conduct . . . and you will deliberately and formally cause sentence of death to be executed by shooting or hanging.” The major did just that, and on August 25 of that year, two natives were hanged beside the graves of their alleged victims.[9]

1 Cullin-La-Ringo Massacre

As we have already seen, the colonial government was committed to ridding the land of the Aboriginal people through callous and unwarranted bloodshed. Such was the case in October 1861, when members of the local Gayiri where shot by Jesse Gregson, along with Second Lieutenant Patrick and his Native Police Troopers. Gregson, who managed the Rainworth station, had accused the tribesmen of stealing a flock of sheep. On October 17, in a retaliatory response, local tribesmen slaughtered 19 white settlers, including women and children, in what is now known as the Cullin-la-ringo massacre, the largest mass murder of whites by Aboriginals in Australian history. It became apparent only after the senseless carnage that Gregson’s sheep were not stolen, as they were later found having wandered from their pasture. Nonetheless, another retaliatory attack was inevitable. Soon after the massacre at Cullin-la-ringo, seven Native Police detachments were deployed by the colonial Queensland government, resulting in the slaughter of 300 to 370 Aborigines.[10] Champion sportsman Thomas Wentworth Wills was Australia’s first cricketer of significance. Being one of the few survivors who narrowly escaped death at Cullin-la-ringo, Wills witnessed the murder of his father on that fateful October day. The frame of mind of the once nationally acclaimed athlete was forever detrimentally changed, and he resorted to alcohol to escape his torments. By 1869, his career was in ruins, and his temperament was degrading. Wills was eventually confined at the Kew Lunatic Asylum, and on May 2, 1880, he took his own life at the age of 43.