There are taste buds in strange places and people who taste the unbelievable. The tongue is also amazingly uncharted—sensing the tasteless, switching sensations, and even producing virtual flavors.

10 Expensive Wine Tastes Better

Certain information can skew a person’s ability to taste what is really being served. In the case of a marketing test for wine, tongues and brains were fooled for the better. In 2015, volunteers were told that they were about to sample five bottles. Prices ranged from £3–£55 per bottle. In reality, they sipped three brands with two different price tags. Blissfully unaware that they were being served cheap slosh, the volunteers reported—and reacted physically—as if the wine was tasty and refined. The belief that the glass contained a quality drink was enough to change their neurological chemistry. Incredibly, the brain molded the person’s taste according to his or her expectancy of the product’s worth.[1] Price was not the only thing capable of this mental tweak. Researchers also discovered that consumers shelled out more for a heavy bottle and that alcoholic beverages taste better in a heavier glass—all because the brain associates weight with quality.

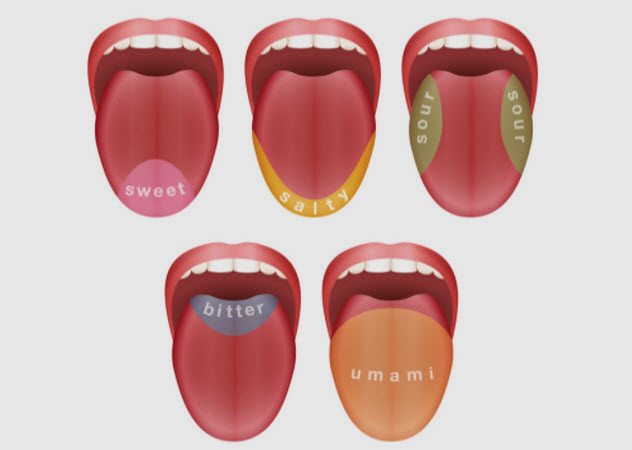

9 The Bloody Mary Mystery

In 2013, the German airline Lufthansa noticed something on their planes that was not really seen back on land. Once in the air, passengers craved tomato juice. Around 1.8 million liters (476,000 gal) were being served annually, making a Bloody Mary as popular as a beer. The unusual phenomenon even encouraged those who would not otherwise drink tomato juice. Once again, volunteers were gathered, this time in a grounded Airbus A310. Drinks were served, but the passengers found the concoction “musty.” However, during simulated flight conditions, the Bloody Mary’s popularity took off. Happy passengers now described it as “pleasantly fruity.” The curious culprit is umami, our fifth taste sensation. The other four (sweet, salty, sour, and bitter) are fearful fliers. Airplane noise, low humidity, and cabin pressure dampens them but not umami, which picks up on savory flavors.[2] Flying conditions could partly be responsible for notoriously bland airline food, but they also explain why a Bloody Mary is a high-altitude favorite. Tomato juice is very savory, which is appreciated by the passengers’ only surviving taste buds.

8 Taste Can Improve Depression Treatment

The ability to taste is intricately woven into emotions. On the darker spectrum, anxiety and depression numb flavors. There is evidence that the blues hamper recognition of how fatty a snack or even milk is. Bad news for those who turn to comfort eating after a stressful day. But taste itself may help people suffering from depression and anxiety to receive more effective treatment. When healthy volunteers were given antidepressants, which contain certain neurotransmitters, their ability to detect bitterness, sucrose, and sourness increased. This pointed to a chemical imbalance in individuals who taste less because of their heavy emotions. This group will benefit from medication but not sufferers who still enjoy a flavor-packed lunch. Since their anxiety or depression does not stem from imbalance, talking therapy may be more successful than pills.[3] Therefore, a simple taste test could either prevent people from lacking medication they need or taking an unnecessary prescription drug. Incredibly, researchers discovered that the antidepressants worked on chemical transmitters within taste buds long before reaching the brain.

7 Battle Of The Sixth Flavor

Convention once stated that the human palate could only detect four flavors. The arrival of umami proved the rule wrong. Some scientists believe that there may even be a sixth flavor. In fact, there are seven sensations vying for recognition. Mice have two receptors to taste calcium. One exists on the human tongue, but its link to the chalky flavor remains unproven. Japanese researchers believe that the calcium receptor is responsible for another unrelated flavor called kokumi (“heartiness”). They claim that compounds in yeast and milt enhance food’s existing flavors. Western scientists have yet to experience it despite eating kokumi-rich food provided by their Japanese counterparts. Then there are piquance (burning) and coolness, which convince the brain of false temperatures. Some feel that these are physical feelings rather than tastes. Two more controversial suggestions hold that fat is a flavor and metals or “metallicity” is another.[4] The most unusual but perhaps the strongest candidate for a new taste sensation is carbon dioxide. The gas adds the fizz to carbonated drinks. In mice, taste cells with the enzyme carbonic anhydrase 4 detect CO2. Mountain climbers take acetazolamide, an altitude sickness drug which inhibits the enzyme. This could be why climbers report flat fizzy drinks—proof of a drug-disabled ability to taste carbon dioxide.

6 The Unusual Tasters

Nobody shares an identical palate with another person. However, most of the population falls into a group that experiences the same basic tastes with approximately the same intensity. For a small percentage, things get strange. There are “thermal tasters” who register cold items as sour and hot items as sweet. Certain individuals are genetically sensitive to coriander. For them, it is like eating soap. At the extreme opposites are tongues that taste little or remarkably well. Nontasters have few taste buds and find food dull. But supertasters have twice as many taste buds as most of the population. Bitterness is the ultimate bane of supertasters, who also enjoy sweeter sugar and saltier sodium.[5] About 25 percent of people are supertasters, but most agree that it can be troublesome. Their pronounced ability to detect minute flavors makes them less likely to enjoy alcohol, rich desserts, and healthy green vegetables. In particular, broccoli is unbearably bitter to supers. Oddly, even though salt tastes strong, most supertasters cannot get enough of it. Researchers believe that it might be because salt mutes bitterness.

5 The Taste Of Water

Almost everybody feels that water has no flavor. If it does, it is usually due to the chemicals in tap water or a container’s aftertaste. Scientists are not ready to agree. If water is truly void of culinary character, then animals’ drinking behavior does not tally. As water is critical for survival, it makes sense that organisms need to identify it by smell and taste. Indeed, water-detecting cells already exist in amphibians and insects. There are signs that such cells could also be in mammals. When an animal feels thirst, the sensation is triggered by the brain’s hypothalamus. The same region also tells it when to stop drinking. But most animals stop long before the gut signals the brain that it feels full.[6] The only explanation is that the mouth and tongue sends messages to the brain. To do this, taste buds must somehow be able to taste water. The human cortex also appears to react specifically to water. Despite the clues, researchers still know very little about how water signals from the mouth and throat reach the brain.

4 Intestines Have Taste Buds

It may sound unbelievable, but the human intestines have taste receptors. Gut buds are not as alien as they sound. The mouth is the start of a long tube known as the gastrointestinal tract, including the intestines. However, taste buds lining the tract function differently than those on the tongue. The latter is all about telling the brain, through taste, what is being placed in the mouth. If palatable, the person swallows. The food reaches the gut buds, which can recognize different tastes. One won’t taste a meal in the intestinal tract, but its receptors’ reactions can be felt as hunger and fullness. Once the brain “tastes” something in the gut, it triggers the release of energy-processing hormones in the tract. This keeps blood sugar levels steady. In this sense, taste buds in the gut have an important health role to play. If faulty, they can cause weight gain or, worse yet, mess with glucose absorption and potentially worsen type 2 diabetes. In the future, a better understanding of gut receptors may be the secret to controlling blood glucose and obesity.[7]

3 The Flavor-Bending Berry

A small red berry from West Africa makes vinegar taste like liquid sugar. In an ironic twist, the so-called “miracle berry” has a bland taste. But once the berry is eaten, one never needs to fear another lemon. Miracle berries turn any acidic food into an intensely sweet experience. The berries contain miraculin, a protein that coats the tongue’s sweet receptors. When the mouth is neutral (neither alkaline nor acidic), miraculin blocks other sweeteners from fastening to the receptors. It even goes as far as deadening the tongue’s ability to taste, which is why the berry’s own flavor disappoints. The fun begins when something sour is added. The protein steals a few protons, changes shape, and distorts the sweet receptors. They turn supersensitive with crazy results.[8] This phenomenon is not unique to miracle berries. The Malaysian lumbah plant pulls the same trick with a protein called neoculin. What is interesting is that neoculin and miraculin are unrelated and differ completely at the molecular level. Also, each attaches to different parts of receptors and yet both do the exact unusual thing.

2 Virtual Flavors

Recently, scientists worked with the elderly and patients who had received chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Both cancer treatments and aging can cause a severe loss of tasting ability. The researchers’ approach was cutting-edge and creative. They used cutlery that virtually enhances the flavor of a meal. Like your lemonade really sour? They invented a cup that can dial the intensity up or down. Another device, a smart spoon, can create or supplement the tastes of a meal. Similar to the cup, a button on the spoon’s handle can lessen or intensify the sourness, bitterness, and saltiness of every bite. Using tiny silver electrodes, flavors are delivered by zapping taste buds with electrical pulses during eating or drinking. Apart from enhancing lunch or restoring taste, the technology also shows promise in another field. Developers believe that people might relax someday in a virtual reality environment where they can sit down and taste those digital nachos.[9]

1 People Who Taste Words

It may sound like fiction, but there are people who can taste words. They even have a name—synesthetes. Individuals with synesthesia experience the overlapping of senses, such as vision and hearing or touch and taste. The rarest of this unusual group are the language tasters. When tested, they even experienced flavors for the unknown names of objects. Cold-called years later, test subjects recalled the flavor of every item. This 100 percent accuracy is something that sets synesthetes apart. Non-synesthetes who are given a list of word-taste associations will forget most within a fortnight. While elusive words produced strange flavors, food names tasted of the actual items. The word “mint” will taste like a mint. Many synesthetes also describe the same word in a similar way. This led researchers to discover that certain sounds within a word, rather than the word itself, triggered taste.[10] The reason why two or more senses blend remains unsolved. One theory states that everyone is born a synesthete, with every sensory region in the brain connected. Eventually, they separate with age. It is suggested that the process does not complete in synesthetes and leaves active links between the senses. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages