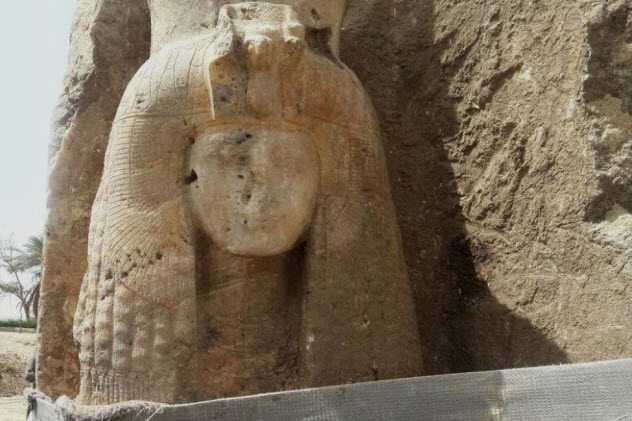

10 The Alabaster Tiye

In 2017, workers near Luxor shifted the enormous statue of King Amenhotep III (1390–1352 BC). While doing so, they discovered that a previously unknown statue had been mysteriously hiding next to the king’s right leg all along. Unlike the colossal Amenhotep, the woman appeared to be life-size and was carved from alabaster. The 3,400-year-old carving is unique and expertly produced, depicting who archaeologists believe is Queen Tiye. Several statues of Tiye, the wife of Amenhotep III and grandmother to Tutankhamen, had already been found inside the mortuary temple on the west bank of the Nile. This was the first not to be made of quartzite. Remarkably, due to being in superb condition, the colors with which the artist originally painted her are still present. This particular Tiye survived a lot—from escaping looters, repeated Nile floods that damaged the temple, and even an earthquake that hit the complex in 27 BC.[1]

9 Nelson’s Women

Centuries ago, British regulations banned women from ships. Not only did they sail but recent excavations on Egypt’s Nelson’s Island showed that women participated in the Battle of the Nile in Aboukir Bay. Archaeologists linked 40 graves to the famous confrontation between the French and the British, led by Rear-Admiral Horatio Nelson, in 1798. Individuals killed in battle received sea burials, while those who succumbed later were interred on the island. During an examination of the burials, an unexpected surprise surfaced. Among the graves of soldiers and sailors were those of babies and women. Despite maritime laws, many officers were allowed to bring their families along.[2] During conflict, these wives weren’t idle. In his memoirs, John Nicoles, a British sailor who fought in the battle, described how women were stationed at the guns, supplying the gunners with gunpowder during the fight. However, none of the female casualties could be identified. One coffin was marked with a metal “G.” Records show three possibilities: a Scottish woman who served on the HMS Goliath and two others mentioned in Navy logbooks who were with two different Guards regiments.

8 The Personality Of Cats

Egyptians were temporarily credited with domesticating the cat when art from 1950 BC depicted a feline under a table. But in 2004, that honor shifted to Cyprus when a human grave included a 9,500-year-old cat. The first prize for domestication may be gone, but a new genetic study could hand Egypt the honor of crafting the modern cats’ affectionate personalities. Four years after the Cyprus find, a cemetery on the Nile’s west bank produced animals 3,500 years younger. Tests on the Nile cats and 200 others showed that the Egyptians likely changed the skittish mousers into loving pets. The first cats came from Turkey—wild critters that moved into human settlements by themselves around 10,000 years ago. They carried the mitochondrial type A. Type C arose in Egypt thousands of years later. But by the first millennium AD, they had spread so successfully that there were two A cats for every C. Experts feel that this occurred because the latter still retained a wild streak and people preferred the A type, which was more domesticated.[3] Indeed, Egyptian art documents how cats were purposefully bred away from feral to pleasant pets.

7 Mystery Toe Rings

On the east bank of the Nile, Pharaoh Akhenaten, the son of Queen Tiye, left behind the ruins of his capital, Amarna. As Akhenaten was a highly unpopular ruler, the city was abandoned shortly after his death and only the dead remained. One grave belonged to a man in his late thirties with signs of bone trauma. The 3,300-year-old skeleton had accumulated the injuries during the man’s lifetime, including fractured ribs and the left radius. The right side was even worse: The ulna, foot, and femur were cracked. It was also on his right second toe that a rare ring was discovered.[4] Made of copper alloy, it is only the second toe ring made of mixed copper that was found in an Egyptian burial. Since a fashion statement would have produced more bodies with toe rings, experts believe that the jewelry might have served as a magical medicine to help with the man’s pain. The right leg, in particular, would have been agonizing since it healed at the wrong angle. But this theory is not watertight. The second toe ring was found in the same cemetery, but its owner showed no obvious signs of a painful condition.

6 The Luxor Mummy

Near the city of Luxor stands a temple that once honored Pharaoh Thutmose III. Located on the west bank of the Nile, the temple was known but not excavated for decades. In 2009, things looked up when archaeologists returned and found a necropolis beneath the sacred structure. One of the 20-plus tombs carried the years better than the rest. Though all had suffered the usual looting and coffin damage, the male mummy’s cartonnage was surprisingly intact. This papyrus-layered body casing had been ruined by termites in every other tomb. But the real mystery of the mummy, buried sometime between 1075 BC and 664 BC, surrounds his identity and link to Thutmose III. The closest clue comes from writing on the cartonnage which speaks of Amenrenef, an honorable person who worked as a royal servant. While this is likely the man’s name, researchers are not sure why he was buried in the temple of one of Egypt’s most famous pharaohs.[5]

5 The Headless Crocodiles

In 2015, a necropolis containing quarry workers and their families was unearthed at Gebel el-Silsila. The site held stone pits on either side of the Nile near Aswan and produced construction blocks around 3,400 years ago. Analysis of the skeletons provided some normal information (the people lived at the quarry and were in good health), but the cemetery also had several odd arrangements. The most confounding was a crypt full of sheep and goat burials with a crocodile guarding its courtyard. The adult croc could have died from natural causes in front of what was likely a sacrificial chamber—but then a second reptile was found. While not together, there were signs that the animals were purposefully placed between the tombs after death. Both were in similar positions and missing their heads. The courtyard croc faced north, and the second one looked south. It is also interesting to note that Gebel el-Silsila’s patron god was Sobek, a crocodile deity. Another unusual discovery concerned two infants. Although they had been interred with great care, they were strangely buried some distance away from the other graves.[6]

4 Tombs With Staircases

Another archaeological dig on the west bank, this time near the city of Aswan, added to 2017’s reputation as a stellar year for discoveries in Egypt. Archaeologists began excavating near the Aga Khan Mausoleum to understand the local history better and were rewarded with an impressive prize. Carved into stone were 10 tombs with huge staircases. The steps led to another chamber where sarcophagi contained several mummies in good condition. Since the find is so new, little is known about the identities or lives of those buried there. But archaeologists suspect that the tombs, which were dug between 712 BC and 332 BC, belong to a previously unknown sector of the nearby West Aswan necropolis. Rediscovered in the 20th century, the necropolis holds a rich collection of graves dating from hundreds to thousands of years old. Several matched the style of the staircase tombs.[7]

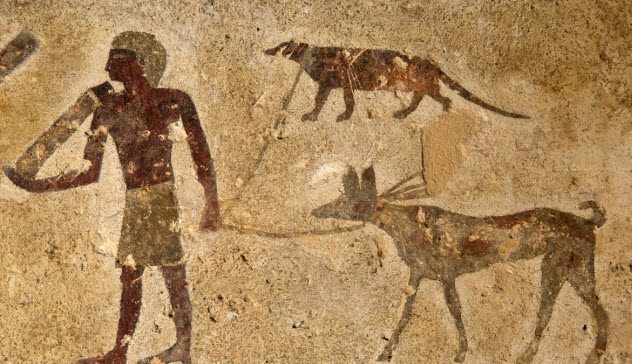

3 Mongoose On A Leash

A team from the Egyptian antiquities ministry recently decided to spruce up a 4,000-year-old cemetery at Beni Hassan. Constructed on the eastern bank of the river, archaeologist Percy Newberry first described the site over 100 years ago. He found something so unknown that most experts didn’t agree with his instincts. On one wall was the painting of a man walking with two animals, both on leashes. The dog was fairly recognizable. Newberry tentatively suggested that the other might be a mongoose. Modern researchers who helped with the renovations had a different view than Newberry’s peers. They noticed that the creature was proportionally identical to the Egyptian mongoose and, even though it was never fully domesticated, definitely leashed. The answer may lie with the dog, a hunting breed, and the presence of birds and human hunters. Perhaps the mongoose was used to frighten the birds out of hiding. Whatever the reason, the scene is unique in Egyptian art.[8] Why it was deemed appropriate for the deceased, a provincial governor named Baqet I, remains a mystery.

2 A Hate Crime

The ruins of Hierakonpolis rest 500 kilometers (300 mi) south of Cairo. The settlement is valuable because the citizens were the ancestors of the ancient Egyptians. But inside Tomb 72 was a stark insight into this pre-pharaoh society. The crypt belonged to an upper-class teenage male. The funeral ceremony called for a gruesome detail—the inclusion of 20 other people. They were likely sacrificed since none showed signs of illness or malnutrition. Also found inside were the remains of dogs, baboons, goats, an ostrich, and a leopard. Shortly after the burial, somebody broke into the tomb. They left the riches alone but pulled the corpse from its resting place and set it on fire. Even the wooden structure that covered the tomb bore traces of flames. The presence of valuable grave goods and the aggression toward the body, which ended up scattered, point to revenge rather than plunder.[9] It will be nearly impossible to say what gripe the intruders had with the youth. One theory suggests class warfare. But other than clear social differences between the graves, there is limited evidence to support this.

1 The Children Who Built Amarna

In 2015, archaeologists made another unexpected find at Amarna, the capital of the unpopular Pharaoh Akhenaten. They exhumed the city’s two worker graveyards. From the first, bodies told a harsh but not unusual tale. They worked hard, ate poorly, sustained injuries, and often died. There was the expected range of different genders and ages. The second cemetery proved to be more surprising, albeit tragic. Most were aged 7–15, with the oldest around 25. The burials were simpler and had little grave goods. Some children were dumped in mass graves.[10] Traumatic injuries abounded in those 15 and younger. Around 16 percent had fractures and damage sustained from performing work too heavy for them. The apparent disregard for their health and the treatment after death indicate that these children were pressed into building the city. Some speculate that they were biblical Hebrew slaves. Experts agree on the slave part. It would explain why the children were treated like expendable commodities. But an initial study concluded that the Amarna graveyards’ population was linked to more diverse groups. Even though their exact origins remain a riddle, the workers’ remains revealed much about how Egypt treated its forced laborers. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages