Although many of these beloved figures sprang fully formed from their creators’ imaginations, some were based on actual people. Others were inspired by characters played by comedians or actors on radio and television shows.

10 W.C. Fields

A United Productions of America creation, the bald, cantankerous, nearsighted Mr. Magoo was an immediate hit when he debuted in 1949. He starred in 53 animated cartoons and won two Academy Awards. Mr. Magoo was immensely popular partly because he embodied “the nation’s postwar optimism.” Like comic actor W.C. Fields, the nearsighted Mr. Magoo had a bulbous nose and narrow eyes. He also mumbled frequently. Despite these similarities, Millard Kaufman, who wrote the first cartoon featuring Mr. Magoo, said that Fields was not originally the inspiration for the character. Dialogue director Jerry Hausner seemed to contradict Kaufman’s account as Hausner said that director John Hubley did not want the character’s voice to sound like that of Fields. (Actor Jim Backus provided the character’s distinctive voice.) Whether or not Fields was originally the inspiration for Mr. Magoo, Fields at least influenced the character fairly soon. After a few films featuring the character were made, Magoo creative director Pete Burness said that he and his colleagues studied the film performances of W.C. Fields for ideas. For example, they used a scene in which Fields waves his cane to “ward off dogs and other undesirables.”[1]

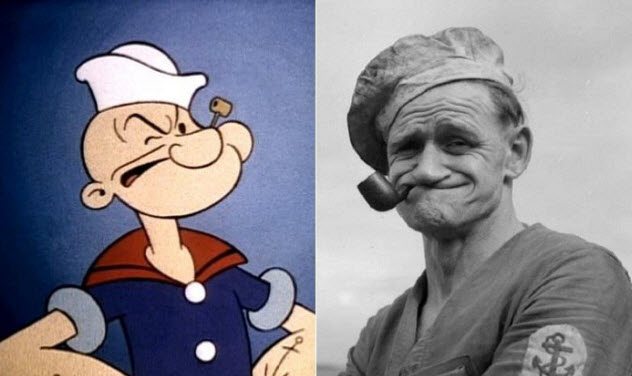

9 Frank ‘Rocky’ Fiegel

Although most of us have probably never heard of him, Frank “Rocky” Fiegel has a claim to fame: He’s the inspiration for Popeye the Sailor, created in 1929 by Elzie Crisler Segar as a new character in Segar’s Thimble Theater comic strip. A resident of Chester, Illinois, Fiegel was “a one-eyed, pipe-smoking river man who had a penchant for getting into fistfights,” just like Popeye. Other characters featured in Popeye cartoons were also inspired by Segar’s hometown friends. Popeye’s girlfriend, Olive Oyl, was based on a thin store owner named Dora Pascal. Wimpy was inspired by William “Windy Bill” Schuchert, who owned the local opera house and loved hamburgers enough to send his employees to buy them for him during breaks in performances. A 183-centimeter-tall (6’0″), 408-kilogram (900 lb) bronze statue of Popeye was unveiled in 1977. The figure stands in Chester’s Segar Memorial Park with hands on hips, pipe in the corner of its mouth, and eyes squinting into the distance. Each weekend after Memorial Day, Chester celebrates a three-day Popeye Picnic with lots of festivities for everyone.[2]

8 Dennis Lloyd Ketcham

Dennis Mitchell, the child star of comic strips, comic books, and a television show, was based on creator Hank Ketcham’s own son, Dennis Lloyd Ketcham. One afternoon, the real-life Dennis was supposed to be napping. Instead, his mother found him removing the mattress and springs from his bed, pulling out drawers from his dresser, and taking down curtains by removing their rods. Exasperated, she cried, “Your son is a menace!” Hank Ketcham, an artist, was inspired. He hastily drew a dozen pencil sketches and sent them to his agent. Ten days later, he received a telegram: Bob Hall, Post Syndicate’s president, was interested and asked to see 12 more sketches. In 1950, Ketcham signed a “once-in-a-lifetime, strike-it-rich jackpot contract.” By the end of the year, Dennis the Menace was appearing daily in over 100 newspapers, each of which paid $3 to $5 per week for the feature. However, the Chicago Tribune paid $100 each week due to its massive circulation. Ketcham added other characters. Dennis’s neighbor, Mr. Wilson, was inspired by Ketcham’s Sunday school superintendent. Dennis’s friend Margaret was based on Ketcham’s own “schoolboy crush.” Then there was Wade, inspired by the local grocer, and Gina, presumably based on actress Gina Lollobrigida.[3]

7 Rita Hayworth, Veronica Lake, And Lauren Bacall

Sexy cartoon character Jessica Rabbit was based on three movie stars. Appearing as Roger Rabbit’s wife in the 1988 full-length animated feature film, Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, Jessica attracted controversy because of her curvaceous figure, sultry demeanor, and sometimes suggestive dialogue. The film focused on the efforts of a shabby private detective to clear his falsely accused client, Roger, of a murder charge. Animation director Richard Williams explained his inspiration for Jessica: “I tried to make her like Rita Hayworth; we took her hair from Veronica Lake, and [Director Robert] Zemeckis kept saying, ‘What about the look Lauren Bacall had?’ ”[4]

6 Margaret Kerry

James M. Barrie’s female fairy, Tinkerbell, was usually represented on the stage by a “flying point of light.” For the 1953 Walt Disney film Peter Pan, she was personified as a winged pixie with a decidedly feminine figure. Her curves proved too indecent for the play’s fans, especially in light of the rumor that Tinkerbell was based on sex goddess Marilyn Monroe. In reality, Tinkerbell was modeled after a different actress, Margaret Kerry. Like any other actress seeking a part in a movie, Kerry had to audition for the role. She was faced with the challenge of conveying the character of a tiny fairy who never said a word. At first, she wasn’t sure how to audition, but she played music and choreographed Tinkerbell making food for breakfast. Studio executives asked Kerry to have Tinkerbell “land on Wendy’s dresser top, measure her hips, and be unhappy with the results.” Impressed with Kerry’s performance, they offered her the part. She reported to work the next week, helping to make Tinkerbell one of Hollywood’s most iconic animated characters. For six months, Kerry’s job was to pose with props and provide the facial expressions, gestures, and other responses that animators would give Tinkerbell to make her come alive as a character.[5]

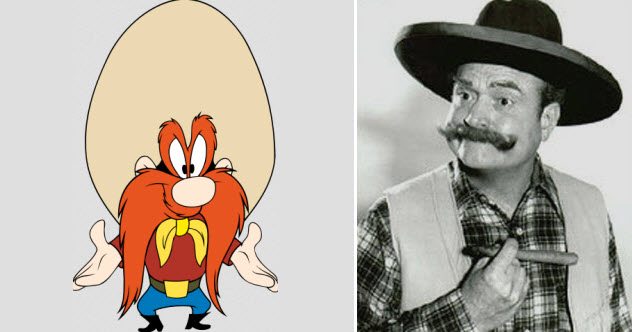

5 Red Skelton’s Deadeye

Movie star and comedian Red Skelton invented a cavalcade of characters during his long and varied career. Starting in vaudeville during the 1930’s, he soon moved to radio, followed by TV—The Red Skelton Show, which aired each week from 1951–1971. One of these characters, Deadeye, played various roles set in the American Wild West, including those of an incompetent sheriff and a cowboy who “couldn’t control his horse or sometimes even himself.” Michael Maltese conceived the story for Hare Trigger, a 1945 Warner Brothers cartoon featuring the feisty, mustachioed, redheaded bandit Yosemite Sam, whose six-guns and sombrero were nearly as big as he was. According to Maltese, the character was based in part on director Friz Freleng. Like the character, Freleng was “short, red-haired, and wore a mustache.” However, Yosemite Sam was later modeled mostly on Skelton’s cowboy Deadeye.[6]

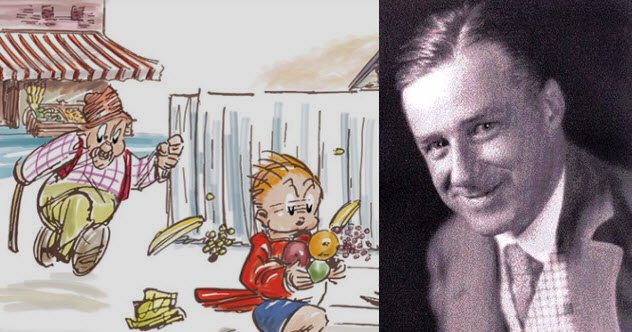

4 Percy Crosby

Some artists pattern their cartoon characters after themselves. Percy Crosby, “the Rembrandt of American cartoonists” and creator of the classic cartoon character Skippy, based his rambunctious alter ego on his own childhood. The precocious boy’s fears echoed Crosby’s own in his youth and those of every generation. Skippy’s prayer, “Oh, Lord, give me strength to brush my teeth every night, and if Thou canst not give me strength, give me strength not to worry about it,” is reminiscent of the pervasiveness of chores and the attendant fear of many young children. Skippy inspired a radio show, a 1929 novel, and a feature film starring Jackie Cooper. Everything from toys to food products was associated with Skippy. Just as his escapades came from Crosby’s childhood, they also mirrored the adventures of many American youths as well, making Skippy an immensely popular character.[7]

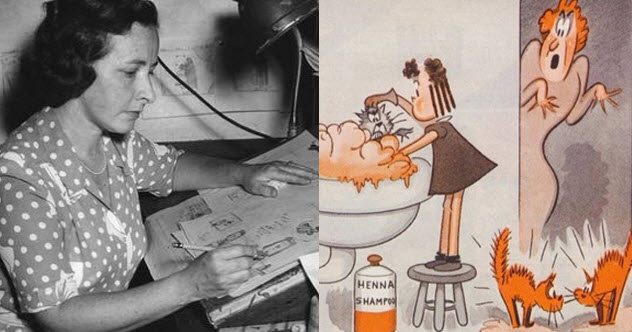

3 Marjorie Henderson Buell

Marjorie Henderson Buell, who signed her work “Marge,” was another artist who modeled her cartoon character, Little Lulu, after herself. Thanks to Lulu, Buell became the first female cartoonist to gain international recognition. In high school, her studio was a converted chicken coop in which she drew cartoons that she sold to the Philadelphia Ledger. By her mid-twenties, she had syndicated two strips, The Boy Friend and Dashing Dot, but Little Lulu established Buell as a famous cartoonist. Little Lulu began as a 1935 replacement for The Saturday Evening Post‘s Henry, which had transitioned from local publication to national syndication. At first, Lulu was a silent character who spoke through her actions rather than her words. In one strip, she insisted on standing in the line to see a movie in a “Men Only” theater, having disguised herself by wearing a mustache. The cartoon was a hit, and Lulu soon pitched a variety of merchandise. In addition, she appeared on everything from lunch boxes to pajamas. Buell said that she chose Lulu because “a girl . . . could get away with more fresh stunts that in a small boy would seem boorish.” Buell thought of Lulu as an independent role model for girls since the character was feminine and nonviolent but also feisty.[8]

2 Classroom Lecture Sketch

Little Lulu’s predecessor, Henry, also became extremely popular as his strip’s national syndication suggests. A pudgy, bald boy who always wore a red shirt, black shorts, and sneakers, Henry was an impromptu creation. As a freelance artist, Carl Anderson contributed cartoons to major magazines such as Judge, Life, Collier’s, and The Saturday Evening Post. He also drew regular strips. But it wasn’t until age 67, when he created Henry, that he attained true financial security. After the Great Depression, he taught cartooning at a vocational school. He drew Henry during a lecture. His students liked the character, so he sent some samples to The Saturday Evening Post. In 1932, the magazine featured the strip every week. Henry was one of the few cartoon characters who didn’t speak. Mute, he depended on pantomime to communicate. He wouldn’t hesitate to blacken Butch the Bully’s eye, if need be, and he enjoyed the company of Henrietta, who looked exactly like Henry except for her pink hair ribbon, her blonde curls, and her pink dress. Henry was also pals with his canine companion, Dusty.[9]

1 Archie Andrews

Archie Andrews lived in Riverdale, where he attended high school with Betty Cooper, Veronica Lodge, Jughead Jones, Reggie Mantle, Big Moose Mason, Dilton Doiley, Midge Klump, Ethel Muggs, and Chuck Clayton. Adults, such as the teenagers’ parents, Principal Weatherbee, homeroom teacher Miss Grundy, and chocolate shop proprietor Pop Tate, made occasional appearances. But Archie comics focused on Archie’s romances with Betty and Veronica, his friendship with Jughead, his rivalry with Reggie, and his interaction with his other Riverdale friends. A radio show, The Archie Show TV series (1968–1969), and several TV specials and sequels were based on the comic strip, as was a flood of Archie-related merchandise. Archie himself was inspired by actor Mickey Rooney, who appeared in silent films as early as 1926 and in “talkies” later on, including films in the 21st century. (Rooney died in 2014.) Archie Comics debuted in 1939 when Rooney was starring in such teen-oriented fare as Andy Hardy’s Private Secretary (1941) and other films in the series. Rooney’s roles in these films provided the model for Archie Andrews. For MLJ Publishing’s cofounder John Goldwater, the success of the Archie radio show and Rooney’s movies suggested the time was right to introduce comic books offering readers something besides superhero adventures. He wanted to market comics more relevant to young people’s everyday lives: “an idealized and sanitized version of the American teenager of the 1940s.” Over the years, Archie comic books were updated to reflect more current themes that appealed to contemporary readers.[10]