Discoveries from this massive era revealed more about extinct human ancestors. Cavemen ran industries, engaged in warfare, and developed unusual social networks. They also had unexpected modern behaviors, inventions, and dangers.

10 Homo Erectus Tool Factory

Northeast of Tel Aviv in Israel, excavations struck stone. More precisely, hundreds of ancient stone tools. Discovered in 2017 at a depth of 5 meters (16 ft), the artifacts had been made by extinct human hands. Created around half a million years ago, the dense cache revealed several things about their creators, an early human known as Homo erectus. It is believed that they saw the area as some sort of Stone Age paradise, prompting seasonal visits. There was a stream, plants, and plentiful game—all necessary to keep the family watered and fed.[1] The pristine site’s best find was a lithic industry. The stonemasons knapped flint into pear-shaped hand axes, likely used for digging for food and butchering animals. The discovery was unexpected, both for its well-preserved state and quantity. This makes the ancient camp a valuable lens to learn more about the lifestyle of Homo erectus.

9 They Made The First Wine

Near the end of the Stone Age in the modern Republic of Georgia, villages whipped up the first wine. Archaeologists purposely set out to make the discovery, but it took them over a year. Finally, in 2016 and 2017, they picked up ceramic shards from 5400–5000 BC and changed wine history. From the villages of Gadachrili Gora and Shulaveris Gora came six jars that tested positive for tartaric acid. This chemical is always a solid indicator of wine residue. In this region, no fruit except grapes yields a strong tartaric signature. Scientists also found that the grape juice would have naturally fermented in Georgia’s warm climate.[2] Interested to see whether the villagers preferred a red or white wine, researchers analyzed the color of the residues. They were yellowish, which suggested that the huge volumes produced by the ancient Georgians were white. The industrious output is a sign that the villagers had already tamed the vine thousands of years earlier. The Republic cultivates 540 different kinds of domestic grapes today. To allow for such variety, domestication must have occurred 8,000 years ago.

8 A Modern Dental Procedure

In the mountains of northern Tuscany, a dentist welcomed patients between 13,000–12,740 years ago. Six such individuals were found in an area called Riparo Fredian. Two teeth, both incisors, showed a dental procedure that any modern dentist would recognize—a filled cavity. It is hard to say if a painkiller was used, but marks on the enamel were caused by a pointed tool. Most likely made of stone, it widened the cavity by scraping out decayed tooth matter. The next bit was both familiar and mysterious. The practitioner prepared a filling of bitumen mixed with plant fibers and hair. Bitumen is a natural tar and used to waterproof things like baskets and ceramics. Seen for the first time as an ancient filling, it was smeared against the inside walls of the gap.[3] Nobody can sufficiently explain why hair and fibers became dental ingredients. The Italian incisors remain the only two examples of this procedure, but it was likely used by more people than just the Riparo Fredian dentist.

7 Long-Term House Maintenance

Most kids are taught that Stone Age families only lived in caves. However, they also built earthen houses. Recently, 150 Stone Age camps were studied in Norway. Stone rings revealed that the earliest housing was tents, probably made of animal skins and secured by the rings. In Norway’s Mesolithic era, which began around 9500 BC, people started building pit homes. This change came when the last fingers of the Ice Age lost its grip on the land. Afterward, a permanent location’s game and vegetation could support a community instead of people having to follow the migrations of the animals they hunted. Pit houses were named for their sunken floors. Some were big enough—around 40 square meters (430 ft2)—to suggest that several families lived together.[4] The most incredible thing was the consistent effort to preserve the structures. Some were abandoned for 50 years before new owners kept up the maintenance. Remarkably, this left behind homes that had been lived in, on and off, for over a millennium.

6 They Avoided Inbreeding

What saved humans as a species could have been an early awareness of inbreeding. In 2017, scientists found the first signs of this understanding in the bones of Stone Age humans. At Sungir, east of Moscow, four skeletons belonged to a group who died 34,000 years ago. Genetic analysis revealed that they behaved like modern communities of hunter-gatherers when it came to choosing mates. They figured out that having offspring with close family, like siblings, was trouble. Those at Sungir showed limited family connections. If they mated at random, the genetic tangles of inbreeding would have been more obvious. Like today’s hunter-gatherers, they must have looked for partners through social ties with other tribes. Researchers believe this network was quite extensive, especially for the smaller groups.[5] The Sungir burials were complex and ritualistic enough to suggest that ceremonies accompanied life’s milestones—like death and marriage. If so, Stone Age weddings would be the earliest human marriages. A lack of understanding of marriage networks may have doomed Neanderthals, whose DNA shows more inbreeding.

5 Women Blended Different Cultures

In 2017, a study looked at ancient homesteads in the Lechtal in Germany. These dated back to around 4,000 years ago when there were no large settlements in the area. When the remains of the inhabitants were investigated, a surprising tradition was discovered. Most families were started by women who left their villages to settle in the Lechtal. This happened from the late Stone Age to the Early Bronze Age. For eight centuries, women, likely from Bohemia or Central Germany, preferred the Lechtal’s men. This foreign female mobility was key to spreading cultural ideas and items, which in turn helped to shape new technologies. The discovery also showed that previous beliefs about mass migration needed adjustment. Even though the women relocated extensively to the Lechtal, it happened on an individual basis.[6]

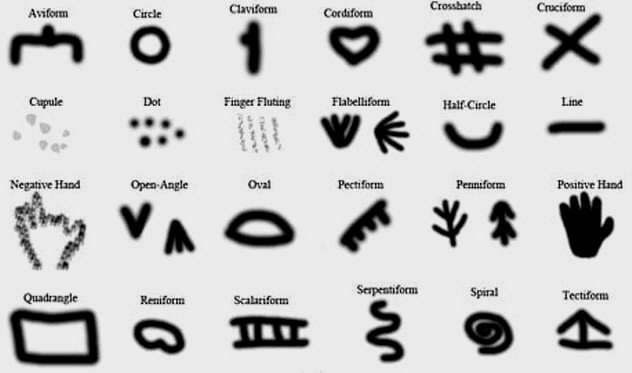

4 A Written Language

Researchers may have discovered the world’s oldest written language. At its barest, it could be a code representing certain concepts. The Stone Age symbols are historic but were ignored for years despite countless visitors trooping into the caves every year. The caves in Spain and France also contain another attraction—large chambers filled with some of the most incredible art in the world. Hidden between the ancient herds of bison, horses, and lions are tiny marks. Unlike the realism of the anatomically drawn animals, the marks are clearly symbols arranged to represent something abstract. Twenty-six signs repeat against the walls of around 200 caves. If they represent information, it pushes the invention of writing back to 30,000 years ago. However, the roots of the curious script may be older. Many of the French symbols, painted by the Cro-Magnon people, have been found in ancient African art. One in particular, the open-angle sign, is engraved at Blombos Cave in South Africa. Artifacts at Blombos have been dated to 75,000 years ago.[7]

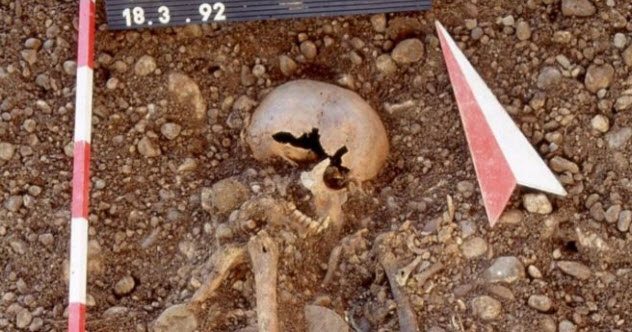

3 The Nataruk Massacre

Stone Age cultures produced breathtaking galleries of art and wide social networks, but they also engaged in warfare. In one case, it was just senseless slaughter. In 2012 at Nataruk in northern Kenya, a university team found bones protruding from the soil. They were fractured knees. Clearing away the sand, the scientists found a heavily pregnant Stone Age woman. Despite her condition, she had been murdered. Around 10,000 years ago, somebody tied her up and threw her into a lagoon. The remains of 27 others—six children and several more women—were with her. Most bodies showed the effects of extreme violence, including blunt force trauma and even bits of weapons stuck in bones.[8] It is impossible to say why the group of hunter-gatherers was exterminated, but it could have resulted from a dispute over resources. During that time, Nataruk was lush and fertile, with fresh water—a priceless grab for any tribe. Whatever happened that day, the Nataruk massacre remains the oldest evidence of human warfare.

2 The Plague Arrived

By the time the bacterium Yersinia pestis was done with 14th-century Europe, 30–60 percent of the population was dead. In 2017, ancient skeletons showed that the plague entered Europe during the Stone Age. Six individuals from the Late Neolithic and Bronze Age tested positive for plague. They covered a wide geographical area, hailing from Lithuania, Estonia, Russia, Germany, and Croatia. Considering the different locations and two eras, researchers were surprised when the Y. pestis genomes from each case closely matched. Further investigation determined that the bacterium probably hitchhiked from farther East when people poured in from the Caspian-Pontic Steppe (Russia and Ukraine). Arriving around 4,800 years ago, they brought a unique genetic marker with them. This component showed up in European remains with the earliest traces of plague, a strong indication that the steppe people brought it with them.[9] It is not known how deadly Y. pestis was during those days. But it is possible that the steppe migrants fled epidemics back home.

1 A Musical Brain Evolution

In the past, it was thought that Early Stone Age tools evolved alongside language. But the revolutionary change—from simple to complex tools—happened about 1.75 million years ago. Scientists are not sure if language existed back then. In 2017, they showed volunteers how to make simple tools (Oldowan flake and pebble instruments) and the post-evolutionary advanced Acheulian hand axes and cleavers. One group watched videos teaching them how to knap. The second group watched the same footage but without sound. While the participants knapped away, their brain activity was analyzed in real time. Scientists found that the jump in expertise was not solidly rooted in language. Instead, for the more difficult tools, the brain activated regions used by modern piano players. This network included visual memory, complex action-planning, sound, and sensorimotor information.[10] The brain’s language center only activated in volunteers who heard the videos’ instructions, yet both groups successfully made Acheulian tools. This could solve the mystery of when and how the human species shifted from apelike thinking to cognition. It would appear that 1.75 million years ago, the “musical” network evolved for the first time and so did human intelligence. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages