Often, discoveries inside or near them reveal ancient mindsets and mysteries from a time when volcanoes were sacred locations. Even in the aftermath, within ash layers and glass, scientists are finding entire forests, ancient seas, and chapters of human history.

10 A Future-Predicting Fossil

Around 90 million years ago, a big aquatic bird died in what is now the Canadian arctic. Called Tingmiatornis arctica, the bird looked like a blend between a cormorant and a seagull. When it was discovered in 2016, the prehistoric bird not only became one of the oldest in the northern hemisphere but also set the record straight. Scientists had always believed that heavy global warming blossomed 93.9–89.8 million years ago. Despite the roast factor, it was also thought that the Canadian arctic continued to produce seasonal ice. The fact that Tingmiatornis perched in the area makes that impossible. The bird’s features enabled it to dive for food. Ice would have prevented the species from feeding or hanging around.[1] Other fossils and soil samples showed that it lived in a very different arctic—a hot volcanic landscape populated by dinosaurs and reptiles. These volcanoes spewed enough carbon dioxide into the air to trigger a greenhouse effect. By providing a more accurate ancient ecosystem, Tingmiatornis provides a glimpse into what a future world too hot for arctic ice could look like.

9 A Miniature Universe

Near Mexico’s Iztaccihuatl volcano is a remarkable pond. The lake is noteworthy eye candy, but when it was drained recently, a stone shrine was discovered inside. The Aztec architects did something amazing. They arranged the stones against the pond’s mirror effect in such a way that the monument appeared to be floating underwater. Located at the foothills of the Iztaccihuatl volcano, this tetzacualco (“shrine”) adds to a collection of artifacts found at the archaeological site of Nahualac (AD 750–1150). Most of the items—such as pottery, rock fragments, and organic remnants—have been linked to Tlaloc, an Aztec rain god.[2] As the shrine is clearly a sacred place, archaeologists believe that its design was meant to show how the Aztecs imagined the universe. Not just the stars they saw at night but a model of their mythical world. The entire site, which includes a valley with springs feeding the pond, could have been a way to evoke the primitive waters from which the Aztecs believed that everything sprang.

8 An Outlaw’s Cave

In 2014, cave explorers decided to spend their day in Snaefellsnes National Park in Iceland. While investigating the Neshraun lava field, they found a cave containing old-looking artifacts. There were signs of a small fireplace, horse bones, and what could have been a bed. The remains were around 900 years old. Experts believed that somebody probably hid there in the 11th or 12th centuries. However, they do not quite know what to make of the person’s decision to stay in the cave.[3] Nevertheless, the individual’s disregard for the law was clear. This came in the shape of the horse bones, which appeared to belong to an animal that had been slaughtered for dinner. When Christianity was adopted in Iceland in AD 1000, horse meat became a forbidden food. Even before the law came into effect, people rarely snacked on a steed. This made the cave occupant’s meal not only unlawful but also incredibly unusual. The mystery is an exciting one to explorers, who believe this is proof that Iceland’s lava fields holds more archaeological surprises.

7 Giant Rings

Inside South Africa’s Pilanesberg National Park are circles so large that they resemble mountains and valleys. In reality, these are the scars of an ancient volcano that repeatedly erupted. A NASA satellite snapped enough details to reveal the birth and demise of the billion-year-old volcano. It began as an embryonic “hot spot,” pooling lava that eventually burst through the crust with immense force and volume. Not all the magma was released, however. Some cooled and solidified within the Earth, seeping into circular cracks and adopting their shape. These are known as ring dikes. Highly uncommon, only a few exist in the world. During the volcano’s million-year life span, the process repeated several times. Each eruption stamped out a new underground ring. The Pilanesberg volcano became dormant after continental plates shifted it away from the hot spot.[4] The following millennia scrubbed the location with erosion until the dikes, almost perfectly round, rose to the surface. The tallest point is Matlhorwe Peak, which is around 1,560 meters (5,118 ft) high.

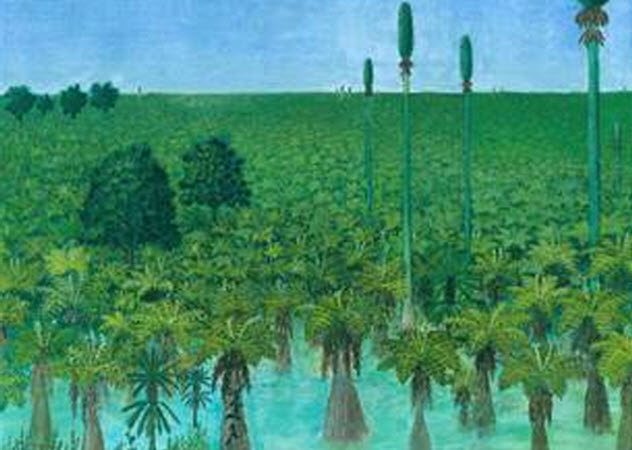

6 A Fossilized Forest

When a volcano blew its top around 300 million years ago, it froze a tropical forest in time. The doomed landscape once thrived in modern-day Inner Mongolia. During the disaster, the forest smothered beneath a blanket of volcanic ash nearly 100 centimeters (39 in) thick. At the time, Earth lacked continents except for the supercontinent known as Pangaea. But despite staying buried for so long, the newly discovered plants were in pristine condition. It was like a free day at a candy store for researchers, who got to see actual trees and foliage that blended the Permian-era ecosystem together.[5] The ash layer was not high enough to preserve standing trees. But some fell during the event and were buried inside the ash layer. This rare view gave a detailed image of the forest’s layers. The upper canopy was woven by species of trees 25 meters (82 ft) high from the genera Sigillaria and Cordaites. Below the first, a secondary canopy consisted of tree ferns. At the bottom were communities of cycads and Noeggerathiales (extinct spore-producing trees).

5 The Campanian Ignimbrite

In 2012, scientists decided to reassess an ancient super-eruption in Italy. The Campi Flegrei volcano got moody around 39,000 years ago, and it became Europe’s biggest eruption in 200,000 years when it exploded. To gain new insight, the team focused on the so-called Campanian Ignimbrite. These were the massive ash fields left behind by the volcano. After investigating 115 sites for exact measurements, researchers reverse engineered the event and came to the conclusion that the eruption was epic.[6] Around 250–300 cubic kilometers (60–72 mi3) of ash was ejected over an area of 3.7 million square kilometers (1.4 million mi2). It surpassed previous estimates, which suggested a volume up to three times less. In addition, 450 million kilograms (990 million lb) of sulfur dioxide was released. The toxic cloud cooled an already frigid Ice Age and could have caused eastern Mediterranean Neanderthals and humans to die off and the survivors to leave. The ash contained fluorine. This infiltrated the plants eaten by these two groups and likely caused fluorosis in some. The condition damages internal organs, teeth, and eyes.

4 Toba Shrank The Human Gene Pool

Between 50,000–100,000 years ago, humans became an endangered species. The modern population’s limited genes suggest that diversity was lost because humans were few. In 2009, the smoking gun for mankind’s precarious position was found. About 73,000 years ago, a volcano did its thing on the Indonesian island of Sumatra. It made the Neanderthal-killing Campi Flegrei look like a pimple. Called the Toba eruption, it spewed enough ash into the air to block sunlight for six years. Where Campi Flegrei caused temperatures to fall by 1–2 degrees Celsius (1.8–3.6 °F), Toba yanked it down a devastating 16 degrees Celsius (28 °F). An Ice Age followed for 1,800 years. The eruption could explain why humans almost joined the dodo, but proof was needed. Thus, researchers scooped up some Toba ash to find ancient plant remains. The tests revealed environmental destruction on a massive scale. For 1,000 years after Toba, India’s forests died off in large swaths and were replaced by sparse vegetation suitable for arid lands.[7] Lower temperature means less rain. The change in landscape showed that Toba’s fallout caused deforestation and cold weather. In addition, it likely threatened humans with extinction.

3 Where Africa Breaks In Two

Africa is spawning an island. The full process will take 10 million years. But in Ethiopia, things are moving fast. In 2005, scientists discovered a speedy split. Within 10 days, a crack opened to a width of 8 meters (26 ft) and ran 60 kilometers (37 mi). It is caused by underground eruptions and deep lava rising to the surface. Remarkably, the crack is the start of a new ocean. As volcanic activity increases the fracture, the Horn of Africa will detach from the rest of the continent. The southern parts of Ethiopia and Somalia will turn into an island as a new sea floods in between it and the much-reduced continent.[8] The rate at which this is happening is truly unusual. Normally, such changes take millions of years, but the odd continental crack has different ideas. This is also a rare opportunity for geologists to witness the birth of a brand-new sea, a process usually hidden beneath the waves.

2 Ancient Water In Glass

Deep-sea volcanoes brought another previously unseen process to the surface. Scientists already knew that seawater infuses the ocean floor with hydrogen and boron isotopes. But the deeper tectonic plates sink into the mantle as they get more parched of seawater and its chemical elements. For scientists interested in studying the recycling of ancient water, it was like looking at a fingerprint without lines. At some point, the hydrogen and boron isotopes fade away as if seawater reaching the mantle would just disappear. However, the Manus Basin of Papua New Guinea provided the truth. There, underwater volcanoes erupted 1.6 kilometers (1 mi) beneath the surface and the depth’s pressure sealed water within volcanic glass. Analysis of the glass returned a surprise. The seawater came from deep within the mantle and had been preserved for a billion years.[9] This suggested that plates which sunk in antiquity could resurface. Also, surface water does not always vanish when catching a ride with plates deep into the Earth. The geology at the Manus Basin appears to be unique. The volcanoes release a mixture of hydrogen and boron isotopes found nowhere else. This blending of prehistoric seawater with the modern ocean helps scientists understand how Earth recycles water and other elements.

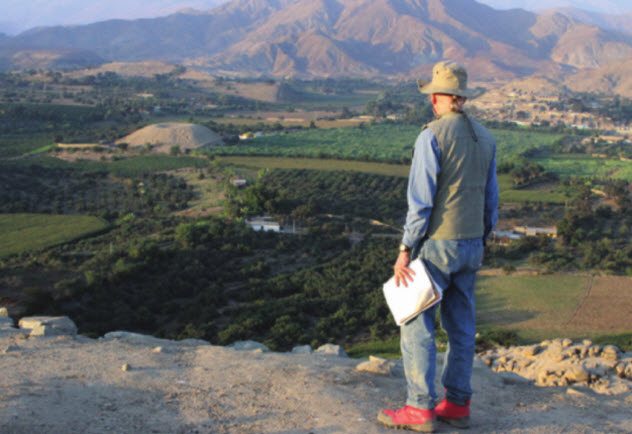

1 The False Volcano

In Peru, a curious structure soars almost 15 meters (50 ft) high. During the 1960s, archaeologists in Nepena Valley noticed the mound. Despite recognizing it as artificial, its existence was recorded without apparently being investigated. As El Volcan’s name suggests, it resembles a volcano. A serious investigation in 2017 made the pyramid even more mysterious. Nobody knows who built it between 900–200 BC or the inspiration behind the cinder cone shape. Three theories competed—looters, erosion, and a deliberate attempt by the builders to make a fake volcano. But erosion cannot explain the missing material from the inner pit—approximately 2,135 cubic meters (75,400 ft3) in volume. Looters would have dumped it at the site, and they wouldn’t have stayed to transform a place they were robbing into a cone. The only conclusion is that the original builders designed it that way. Also found inside El Volcan was a hearth roughly dating to AD 1563. This provided a clue about the pyramid’s purpose. In the years before, a series of eclipses occurred in the region. During that time, the people greatly celebrated such events. This makes it likely that the volcano was somehow a part of the party.[10] Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages