But the most remarkable are the unexpected realities, behaviors, and skills that big ancient Greek projects tend to reveal. Lost cities, strange relationships with earthquakes, battles, and intricate industries all left their footprints for archaeologists to follow.

10 An Ancient Mall

Back in the day, a cluster of shops was called a portico. In 2013, archaeologists were dusting off the edges of the ancient coastal city of Argilos when they found its portico. Located in Greece near the Aegean Sea, the ancient strip mall supported a throng of shoppers around 2,500 years ago. This makes it the oldest one ever found in northern Greece. However, it is unique from other porticoes. When archaeologists cleared seven of the rooms, it became obvious that each was different. Instead of a single state-backed architect, it would appear that each shop owner constructed his own place of business. This left the 40-meter (130 ft) shopping center with several architectural styles.[1] It is likely that the portico originated from private owners rather than the city itself. Artifacts such as coins and vases helped to date the ruins. They also revealed more about the daily lives of the citizens, who were forcibly relocated in 357 BC. Philip II of Macedon decided to populate the nearby Athenian outpost of Amphipolis and nabbed the residents of Argilos.

9 City On A Hill

For around two centuries, archaeologists gave a small Greek village the uninterested eye. Found in western Thessaly on a hill called Strongilovouni, the settlement once bustled in what was considered an ancient “backwater.” In 2016, the ruins were scanned with ground-penetrating radar. What it found changed everything the experts thought they knew about the area. The village turned out to be an important metropolis. Images revealed structures resembling a street grid and town square. City walls enclosed a space measuring 99 acres. Some of the ruins that were aboveground were identified as part of the city’s walls, towers, and gates. Named Vlochos, it appeared to have thrived from the fourth to the third century BC. It joins the club of large cities abandoned for unknown reasons, though the exodus could have had something to do with the Romans invading the region.[2] The discovery of Vlochos returned a piece of the area’s true history and also proved that large finds are still possible in Greece.

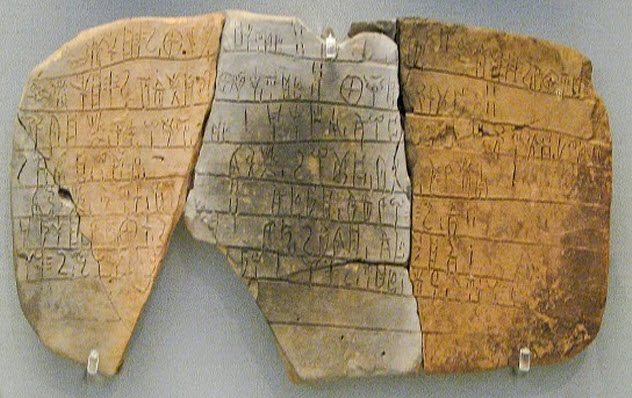

8 Revision Of Mycenaean Civilization

In Mycenaean Greece, advanced plumbing, art, and architecture was believed to be restricted to the palaces. But recently, a newly discovered site forced the story line in another direction. The Mycenaean kingdom of Pylos (1600–1100 BC) had regional capitals, and the new arrival was one of them. Excavations at Iklaina revealed the unexpected—that the “elite” trademarks were also featured elsewhere in settlements. This included well-developed urban structures, Cyclopean architecture, linear B script, and remarkable murals.[3] This sharply changed conventional beliefs about the Mycenaean states. Interestingly, the remains also hinted at a violent conflict between Iklaina and the kingdom of Pylos, to the point where the latter absorbed Iklaina. The reach of Pylos, including its semi-independent regional cities, was around 2,000 square kilometers (772 mi2). It was also among the first in the West to form states as the ruling political institution.

7 Earthquakes Held Special Status

Fault lines may have made for popular real estate in ancient Greece. It sounds counterintuitive or downright stupid, but in 2017, the University of Plymouth found fault lines running beneath several major Greek sites. The Aegean region is fraught with these shakers, but their proximity to sacred structures may not be accidental. Some of the sites include the famous ancient cities of Mycenae, Hierapolis, and Ephesus. Another location is the Temple of Apollo, where the renowned Oracle of Delphi resided. The temple’s subterranean chamber, used for divination, sits on a fault line. Researchers believe that the ancient Greeks may have viewed earthquake-affected land as being special. It could have something to do with natural springs. Most settlements and rituals needed a water source, but it is also known that the Greeks revered those with unusual qualities. When springs leak from faults, they sometimes produce dangerous or hallucinogenic gases.[4] Indeed, many of the springs in the Aegean are connected to earthquake lines. In that regard, it is likely that earthquakes played a bigger role in the placement of Greek buildings and cities than previously believed.

6 The Delos Discoveries

The island of Delos is important to Greek history and mythology. Said to be the birthplace of the god Apollo and the goddess Artemis, it is already one of the most valuable archaeological sites in Greece. The usual year-round excavations recently added an important angle to the mythical island. Not a lot is known about its earlier history, especially how locals related to the outside world. But the new discoveries proved that ships arrived to dock at a major trading harbor. Off the coast, deep under the sea, were ancient port and coastal ruins. One remarkable structure was the main breakwater. It was designed to safeguard the harbor against damaging winds and measured 160 meters (525 ft) long and 40 meters (131 ft) wide. The most exciting discovery was a sunken fleet of ships from different eras and countries. Some were as old as 2,000 years. Most hailed from the Mediterranean and carried amphorae from Italy, Africa, and Spain. One Hellenistic vessel brought oil and wine jugs before it sank. Thanks to the ships and their cargo, it is clear that Delos traded throughout the Mediterranean during the Hellenistic period.[5]

5 Legendary Battle’s Naval Base

Fought at sea in 480 BC, the Battle of Salamis was the turning point in the Persian Wars, when Persia attempted to take over Greece. Although the Persians significantly outnumbered the Greeks, the Persians lost. In 2016, researchers found the location where Greece gathered her fleet in preparation to clip the Persians’ wings. The Greek island of Salamis yielded the telltale ruins. Found underwater at Ampelakia Bay were walls, partial buildings, port structures, and fortifications such as towers and breakwaters. The large ruins dated to the Classical and Hellenistic periods when the Persian Wars raged. The location is also perfect because the famous battle occurred in the nearby straits. The case was clinched when researchers decided the port matched ancient descriptions about where the Greeks gathered and launched their ships.[6] The rediscovery of one of history’s most renowned naval bases is a stark reminder of how much was at stake, even if the ancient Greeks were unaware of it at the time. Some scholars believe a Persian victory would have prevented the remarkable influences that the modern world inherited from Greek culture.

4 A Unique Silver Mine

Near the Aegean shore, in Thorikos, archaeologists found what could have been the seat of Athenian power. In 2016, investigations uncovered an underground complex. The silver mine had an infrastructure never before seen in the area’s Classical period (fourth century BC). Untouched for 5,000 years, the layout and scope spoke of remarkable mining skills. It ranged from large open galleries to cramped tunnels requiring a physical dexterity the archaeologists struggled to match. The miners were mostly slaves laboring under harsh and hot conditions. During the earlier stages in the Classical period, they carved a network of quadrangular shafts. These are a testament to exceptional mining organization and extraction. However, near the end of the century, tunnels were precision built to connect two levels of extraction. This architecture was managed down to the millimeter, a feat still not fully understood. But the vast technology and resources needed to extract the silver would have been unmatched in the ancient world. The fact that silver ore was richly exploited over several millennia likely made the district a factor behind Athen’s power in the Aegean.[7]

3 The Harbor Of Corinth

Around a century after the Romans razed the Greek city of Corinth (146 BC), Julius Caesar rebuilt it. In 2017, some of the most impressive, large-scale engineering came to light when the ancient port was excavated. Called Lechaion, the forgotten harbor once thrived in the Gulf of Corinth. It had two main sections. The inner port spanned 24,500 square meters (264,000 ft2) while the outer port was 40,000 square meters (431,000 ft2). It had mammoth quays and monuments, such as the now-missing lighthouse. The mysterious ruins of another large building stand on an inner basin island.[8] As impressive as the stone structures are, Lechaion’s sediment preserved something even rarer—the wooden infrastructure used by the ancient builders. Usually, wood rots away. But the harbor sediment perfectly preserved the pilings and caissons that served as foundations. Wooden elements in ancient engineering are considered extremely valuable. Lechaion’s will undoubtedly add more insight into the building techniques of the Roman Empire.

2 A Greek Gymnasium In Egypt

The Greeks took their culture wherever they went. Egypt was no different. When Alexander the Great swept through Egypt, a Greek flavor touched its traditions and architecture. In 2017, archaeologists unearthed Egypt’s first gymnasium in the ancient village of Philoteris. In Greece, these structures welcomed young upper-class athletes who spoke Greek and wanted to engage in sports and philosophy debates. The one in Philoteris was impressive. About 2,300 years old, it had a dining hall and another large space that might have been a meeting room. The latter was once stacked with statues. There were many gardens, a courtyard, and a racetrack 200 meters (656 ft) long. It is likely that the elite of Philoteris, which is about 145 kilometers (90 mi) southwest of Cairo, built the gymnasium to make their village appear more Greek.[9] The unique discovery is not entirely unexpected. When Philoteris was founded, about a third of the 1,200 villagers were Greek-speaking settlers. Ancient Egyptian records also mentioned countryside gymnasiums during the Ptolemaic period, which matched the place and age of the Philoteris building.

1 Pyramid Plumbing

The Greek island of Keros is a mountainous protrusion from the Aegean Sea. Around 4,000 years ago, humans carved the cone-shaped land into terraces to resemble a stepped pyramid. To make it gleam in the sunlight, it was clad with a thousand tons of imported white stone. The pyramid itself is nothing new. But in 2018, researchers found a surprise when they looked inside—a sophisticated system of drainage tunnels. It dated a full millennium before the advent of the remarkable plumbing of Crete’s Minoan palace of Knossos. Discovered while excavating a large outer staircase, the system’s exact purpose still needs to be determined. The pyramid’s plumbing could have funneled fresh water or removed sewage. Keros became a major ritual center in the third millennium BC. The community that built and maintained the sanctuary populated the nearby island of Dhaskalio. The settlement was exceptional in several ways. Even though Dhaskalio was the region’s most densely settled island and everything from food to material had to be imported, they aced the considerable effort needed to keep the site going. Newly discovered workshops also proved the excellent metalworking craftsmanship during a time when such skills were basic and rare.[10] Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages