This tomb, found at the ancient Macedonian capital of Aigia, has been the subject of intense debate for over 30 years. Does this tomb contain the remains of Alexander the Great’s father, the warrior king Phillip II? Or, are they the remains of Phillip III, poisoned and weakened at a young age by Alexander’s jealous mother, Olympia? While the style of the artifacts in the tomb dates to 316 BC, a generation after the death of Phillip II, in 336 BC, recent facial reconstruction (pictured) shows an injury consistent with the one received by Phillip II at Methone in 355BC; such a wound is unlikely to have been received by the weak Phillip III.

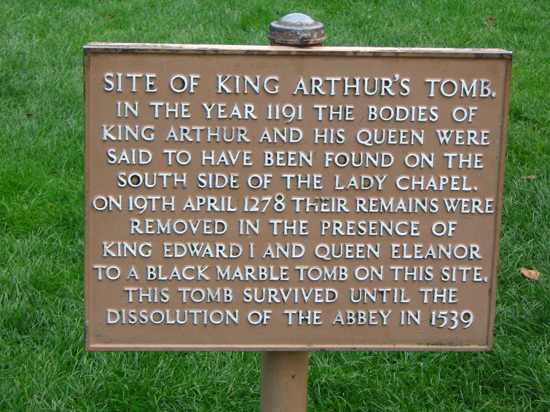

Legend tells us that after being wounded by Mordred, King Arthur was taken across the water to the Isle of Avalon. As it was still an island in the early centuries of the first millennia, a boat would have been needed to take the mortally wounded king to the only medical help available, Glastonbury Abbey. An ancient Welsh bard told of Arthur being buried deep below the earth there. In 1191, monks digging in this spot found a stone. Beneath it was a leaden cross with the inscription “His iacet inclitus Arturius in insula Avalonia” – interpreted to read “Here lies King Arthur buried in Avalon.” The coffin contained two corpses: those of a man and a woman. The bodies were believed to be those of Arthur and Guinevere, but both remain lost following vandalism after the dissolution of the abbey, in 1539.

Long and complicated theories involving the Knights Templar, the Priory of Sion, ancient Merovingian kings, Mary Magdalene and, perhaps, the final resting place of Jesus, himself, surround this picturesque French village and a mysteriously rich priest. Within a few years, this priest went from borrowing a few thousand francs, to building a complex of elaborate and beautiful structures over a period of many years, costing an estimated 23 million francs. During early renovations, Father Francois Sauniere found some parchments and a “Knight’s stone” bearing a carving of two knights riding a single horse (the seal of the Templars), which many believe to be an entrance stone to the crypt that now lies sealed beneath the altar of the church. What this crypt held, and who was laid to rest within it, are mysteries that have yet to be resolved.

The legendary King Midas could turn all that he touched into gold. The real Mydos ruled a Phrygia beset by Cimmerians, in 710 BC. The excavators of a royal Gordium burial mound in 1957 quickly dubbed it the “Midas Mound.” Some historians claim the destruction of Gordium started with these invaders, and that the construction of such an elaborate burial mound must belong to an earlier king. Others point to the pottery and other artifacts, as well as a three ring dating process, as firmly establishing the mound around the 8th century BC, so it could, indeed, be the final resting place of the king doomed to turn his own children into gold.

Entombed in a glacier, the headless Kwaday Dan Sinchi, or “Long Ago Man Found,” was originally dated to around 1420. A later, and more widely accepted, dating put the death of this young man between 1670 and 1850. It is thought he died from exposure, possibly falling through a snow patch into a hole in the glacier (still one of the greatest hazards in traversing glaciers, today). Numerous artifacts were found with the body, including a bone knife and sheath, a spear, wooden walking stick and a pouch with dried salmon. DNA testing found 17 members of the 248 tested First Nation members were related to Kwaday. 15 of those were members of the Wolf clan, leading many to believe this ancestor was also a member of that clan. Kwaday Dan Sinchi was cremated and laid to rest by First Nation members in 2001.

Legend has it that Genghis Khan is entombed in a spot so secretive that anyone who even came near his funeral procession was killed. The 800 horsemen who trampled his gravesite to keep its location secret were, in turn, executed, along with the 1,000 laborers who escorted his body and dug his final resting place. There is a tomb at his palace (pictured), on the Ordos Plateau, but it only contains his personal effects, not his remains. Yet the search for his remains continues, using advanced ground visualization techniques that not even the Great Khan, renowned for incorporating the technologies of the countless people he conquered into his war machine, could not have imagined. Genghis Khan took the greatest treasures from the most advanced empires of the time. Could some of this wealth have been buried with him?

Discovered in 1907, Tomb 55 remains one of the most enduring mysteries of the Valley of the Kings. The wooden shrine was clearly made for Tiye (Ankhanaten’s mother). The magic bricks bear the name of Ankhanaten. The coffin was made for a woman, but altered for a man and a beard was added. The golden death mask was purposely broken, making identification difficult. DNA testing shows the mummy is related to Tutankhamen, but testing also shows that the mummy was a young man in his late teens or early twenties, ruling out Ankhanaten (Tut’s likely father). This also could be the mysterious Smenkhkare, who also, possibly, was the father, or perhaps the uncle, of Tutankhamen. However, too little is known about him to be certain. Who is buried in Tomb 55, and why does it contain such a mismatch of burial goods from a period when burials were highly ritualized and defined?

Stonehenge has long been shrouded in mysteries surrounding its creation and purpose, leading to theories that range from “crackpot” to scientifically analytical. New radiocarbon dating shows that cremation burials at Stonehenge took place from its creation (around 3,000 B.C.), until long after the famous large stones were erected (around 2,500 B.C.), supporting the theory that it was used for royal burials. Previous testing indicated that these burials only occurred over a small period of time. Further giving credence to the “burial of the privileged” idea, is the fact that the number of cremations started out small but advanced in number as more generations flourished. Over a period spanning 500 years, archaeologists estimate that 240 cremation burials took place, indicating that a very select few—perhaps a royal few—were interred near where the sarsen stones now stand.

Viking-era bones found beneath a rosebush at the St. Nicholas Church in Norway, show a lack of fusing of a particular bone in the back of the neck. (St. Nicholas is the patron saint of sailors, among others.) While this skeletal trait has never been found among Norwegians, it is known to be the dominant trait of a single people: the Incans, who thrived in Peru during the Viking heyday. Vikings were known to sail farther than any other culture, and even to have made small forays into North America. Could the Incans, whose empire spanned a continent, have also traveled far? Could Vikings have encountered an Incan in the Northeast Region of Canada, and returned with him to Scandinavia?

Otzi lived 5,300 years ago, and has been the subject of intense examination and debate, as well as a number of hoaxes, since his body was discovered partially entombed in ice in 1991. While tissue and intestinal analysis has revealed to us his last meal, and examination of wounds revealed his likely cause of death, debate still rages over many aspects of this natural mummy. Analysis shows the blood of at least four other people on his knife, arrow and clothing. Was he murdered, shot in the back by companions? Did he, and others with him, fight and win a skirmish with rivals? Was he ceremoniously buried near the spot where he was found? Otzi has revealed much about Europeans in the Copper Age, but a lot of mystery (and a possible curse) still surrounds this ancient man.