The traces they left behind may not be as big as lost cities, but they are no less rare and mysterious. New mummies are breaking old beliefs and revealing new civilizations. Settlements show the realities of the time, invasions, brutal leadership, and even blood sacrifices from otherwise advanced people.

10 The Inca Tree

It was one of those discoveries that surprised everyone because the tree was large and everywhere. Researchers noticed the tall specimens for some time—some grew up to 30 meters (100 ft) tall—but only realized in 2017 that this was a whole new kind of rubber tree. Relatives to this newcomer include poinsettias and other latex-leaking plants from the spurge family. But the latest addition is truly special—a new genus had to be created to fit the species. It is like finding oak or cabbage for the first time. Called Incadendron esseri (“Esser’s tree of the Inca”), they are a common sight along the Trocha Union, an old Inca road in Peru. The canopy tree carpets the landscape from southern Peru to Ecuador.[1] Scientists do not fully understand why it appears to be so successful in a harsh environment. But the 0.6-meter-thick (2 ft) Incadendron is susceptible to the planet’s rising temperatures and deforestation.

9 Elite Skulls

Around three centuries before the Incas arrived in Peru, the Collagua began to press their skulls into long shapes. This tradition began around AD 1300 and lasted for hundreds of years. But skull squashing was not for everyone. In a bid to discover why anyone would deform their children’s heads, a recent study looked at 211 skulls from two Collagua graveyards. It concluded that the cone people were mostly from elite graves. More surprisingly, skull binding did not develop overnight but was refined over many generations. Starting in infancy, boards and cloth were used to press the head into increasingly narrow points. Researchers suspect that there was a bond between individuals who looked different from the norm—and that this united leadership was crucial to their survival against the Incas. The latter arrived in 1450. But instead of going to war, the Collagua elite could have decided to be drawn peacefully into the powerful Inca Empire. Even so, nobody knows what happened to the Collaguas in the end. Similar to their neighbors, the Cavanas, they disappeared.[2]

8 The Paracas Lines

In 2014, archaeologists announced that they found the older cousins of the famous Nazca Lines. Created by the Paracas culture around 300 BC, they were three centuries older than the earliest Nazca design. They were found in the Chinca Valley as part of a complicated artificial environment. The 71 rocky lines were accompanied by large mounds, pyramids, 353 stone cairns, and rocks stacked in circles or rectangles. Several geoglyph lines and mounds were aligned with the June solstice sunset. This was no casual worship of the seasons but likely markers to help people from all over find their way to Paracas-style trade fairs at a certain time of the year. It is also believed that the sites themselves held festivities, tracked time, and had other multiple uses instead of any singular purpose.[3]

7 The Atacama Mummies

It is not every day that one discovers 150 mummies from an unknown culture. But between 2012–2014, their simple graves were unearthed in the Atacama Desert. The individuals were naturally preserved due to being placed directly in the sand, wrapped only in sheaths made of cotton, reeds, or fishing nets. They were not Inca or Tiwanaku because the bodies predated both civilizations by 500 years (4th–7th centuries AD). Luckily, the grave goods were happy to talk. Most of the items were high quality and decorated. From domestic items, researchers could see how this civilization made jewelry, pottery, and weapons. They also learned what these people wore and that they caught fish and combed their hair. The discovery of bows was an incredibly rare Peruvian find. Llama bones in another grave could also readjust the history books as to when the animal first arrived in the region. Remarkably, right next to the cemetery was another graveyard filled with Tiwanaku burials. This later civilization was never thought to have spread their wings as far as the Tambo River delta, where the mummies were found.[4]

6 First Female Governor

In the Chicama Valley stands an ancient adobe pyramid called Cao Viejo. Inside, a mummy rested that changed a big detail about pre-Hispanic Peru. Scholars had believed that women held no power positions. But that changed in 2006 when the so-called Lady of Cao was discovered. She belonged to the Moche culture, which flourished from AD 100 to AD 800. This woman ruled northern Peru 1,700 years ago. Among the grave goods were a crown, large war clubs, spear throwers, and artifacts of copper and gold. The mummy’s face, feet, and legs bore tattoos of spiders and serpents, both magical symbols. Since she was the first female political, religious, and cultural governor of Peru, researchers wanted the meet the Lady of Cao. The closest they could manage was a facial reconstruction. This happened through skull analysis, 3-D printing, and 10 months of painstakingly weaving all the details together. The result was a handsome, capable-looking woman in her twenties. A medical examination showed that her cause of death was likely tied to pregnancy complications or childbirth.[5]

5 Flash Inca Invasion

Ayawiri, a town on a hill in the central Andes, was once called home by about 1,000 people. The citizens belonged to the native Colla civilization. When Ayawiri was recently excavated, archaeologists soon sobered up to the fact that the scene was abnormal. Too many valuables were strewn about. It appeared that the inhabitants had left so fast that there was no time to pack. The amount of valuable metal tools and jewelry, as well as stone implements and useful pottery, is exceedingly rare for an abandoned town. It is believed that Inca warriors descended on the hill with such speed that the Colla dropped everything and ran.[6] Findings suggested that the event happened around AD 1450 and not everyone was clueless about the impending attack. When excavations reached the homes of the wealthier families, several were almost empty of possessions. Aware of the invasion, they departed earlier. But, for some reason, they chose not to warn the rest of the town. Where the Colla people went after they fled the hill remains a puzzle.

4 Geoglyphs From Three Cultures

Early in 2018, National Geographic broke the news that about 50 new “Nazca” designs were found in Peru. However, these were different from the famous geometric and animal-shaped lines. They were smaller (about the size of a football field), only inches across, and mostly depicted human figures. Unlike the Nazca Lines, which spread across the flat earth, the new images crept up hills. In 2017, the previously unknown artwork was spotted by drones during a project to conserve the known sites. Their value does not exist only in the visual differences but also in the fact that they were made by three successive civilizations. This showed that the Nazca (AD 200–700) did not invent the tradition. Instead, they continued what the Paracas started and the Topara culture (500 BC–AD 200) maintained until the Nazca people showed up.[7] It remains a good question to ask: Why did this labor-intensive tradition survive across three cultures? There are many theories, such as representations of constellations, an aid to pilgrims, or a ritual ingredient. The truth is that nobody knows what drove the ancient Peruvians to create giant images in their environment.

3 Prehistoric Hazing

At the ceremonial site of Pacopampa, skeletons with brutal injuries were found in 2017. Considering the history of the Andes, one could be pardoned for thinking that they were victims of war or sacrifice. But then researchers noticed several things that made it implausible. Pacopampa had no defenses, which meant that the people there had no fear of being attacked. Their existence must have been peaceful as far as war was concerned. All the injuries showed healing, so nobody died from the horrific blows. Both sexes were equally bashed, none showed defensive injuries (they took the beatings), and the fractures showed up in the same places (skull, face, limbs, and dislocated elbows).[8] The most important clue came from the fact that none of the skeletons came from elite graves. Everything pointed at a disturbing process. From the 13th to the 6th centuries BC, the ruling class used brutal rituals as a way to maintain their dominance over civilians. Previous excavations had already established that inequality existed at Pacopampa as well as a deep penchant for ceremonies.

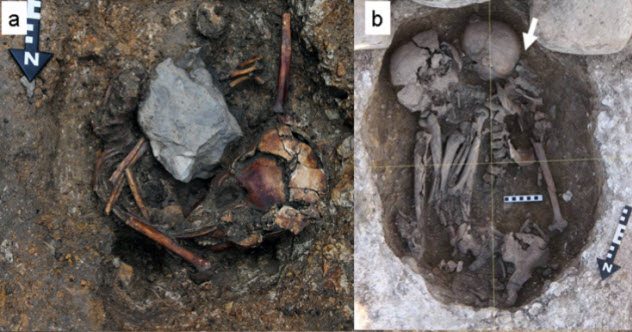

2 Chimu Child Sacrifices

The adults at Pacopampa faced nonlethal ceremonies, but some children from the Chimu culture never survived theirs. They were not meant to. In 2017, construction workers were preparing to install pipes when they stumbled upon human remains. Realizing that the bones were ancient, archaeologists were called to the beach town of Huanchaco. Soon, 77 burials were identified. They were a blend of pre-Inca nations such as the Chimu, Salinar, and Viru. At least 12 were children who died 1,500 years ago. All of the kids’ chest bones showed cut marks, as if somebody had sawed at the ribs to remove their hearts.[9] Apart from the dozen youngsters, there was also a newborn who had been sacrificed. The killings were likely performed by the Chimu culture (AD 900–1470) in a gruesome attempt to please the rain gods. The region was extremely dry. In a stark contrast, the Chimu people are remembered for their advanced crafts and engineering. Their capital, Chan Chan, is recognized by UNESCO as an “absolute masterpiece of town planning.”

1 Living Royal Incas

The last Inca emperor fell in 1533 when he was murdered by the Spanish. Atahualpa had ruled the biggest empire of its time and the culture that produced engineering treasures such as Machu Picchu and a 40,200-kilometer (25,000 mi) network of roads from Colombia to Argentina. After the emperor’s execution, the empire was obliterated. Dutch Historian Ronald Elward moved to Peru in 2009 and spent years looking for any royal descendants. He identified 25 noble family names directly linked to Atahualpa. Remarkably, most living descendants showed up in the lower social groups. This could be because indigenous surnames are preserved in rural areas but frowned upon in the cities. One woman traced by Elward was 40-year-old Roberta Huamanrimanchi Tupahuacayllo. During the day, she looks after other people’s children. On her mother’s side, Roberta inherited royal Inca blood. Her father collects family skulls, an ancient Inca tradition.[10] Elward’s research was supported mainly by parish records and interviews. In turn, it provided the groundwork for Peruvian geneticist Ricardo Fujita. Testing those who claimed descent from Atahualpa’s father, Huayna Capac, DNA linked around 35 people to indigenous populations near Lake Titicaca. This supports the myth that the Inca originated in that region. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages