10 Sophie Ursinus

In 1803, Sophie Ursinus was arrested on suspicion of trying to kill her servant with plums laced with arsenic. Police launched an inquiry and uncovered a few mysterious deaths in Mrs. Ursinus’s past. Her husband, a Prussian counselor named Theodor Ursinus, died in 1800. Her aunt died in 1801 after leaving Sophie an inheritance. One of Sophie’s lovers had died in 1797. Evidence showed that the lover likely died of consumption, but the husband and aunt’s deaths were more ambiguous. Police decided to dig up their bodies.[1] Renowned German chemist Martin Klaproth and his assistant, Valentin Rose, were brought in to consult on the case. The stomachs of the victims showed evidence of coming into contact with an irritant, but the scientists still opined that Theodor Ursinus died of natural causes. The aunt’s death, however, was ruled murder by poison. Sophie Ursinus was convicted of one murder and one attempted murder and sentenced to life in prison. More importantly, though, Valentin Rose continued working and developed a new method of detecting arsenic a couple of years later. By cutting up the stomach and boiling it in distilled water, Rose obtained a concoction where organic matter could be filtered out using nitric acid. The remaining liquid created a precipitate which could be tested for the presence of arsenic.

9 The Murder Of Gustave Fougnies

Hippolyte Visart de Bocarme was a 19th-century Belgian nobleman who was convicted in 1851 by using forensic medicine of the first recorded murder by nicotine poisoning. Visart de Bocarme married Lydia Fougnies in 1843. Despite coming from a noble family and owning a castle in Bitremont, Visart de Bocarme had constant money issues. Lydia’s father had a large estate, but it went to her older brother, Gustave. Hippolyte was hopeful that, due to his brother-in-law’s poor health, he would eventually inherit the Fougnies’ fortune. Things went sideways for Visart de Bocarme in 1850 when Gustave announced his intention to marry. Hippolyte and Lydia realized the only way to get her family estate was if her brother died before marriage. On November 20, 1850, the two invited Gustave to their chateau. He later died during dinner of apparent apoplexy. A cursory examination showed Gustave Fougnies was forced to swallow something corrosive before dying. Belgian chemist Jean Servais Stas was brought in to consult. In a world first, Stas was able to deproteinize organic tissue taken from the victim’s organs and identify the presence of nicotine after diethyl ether extraction.[2] Stas proved that Visart de Bocarme poisoned his brother-in-law using nicotine extracted from tobacco leaves. At that stage, other experts believed it was impossible to isolate and identify organic poisons from organ tissue. Stas’s method is still used today, fundamentally unchanged, to detect alkaloid poisons.

8 Pierre Voirbo

Blood analysis represents one of earliest “instruments” in the forensic tool bag. Historically, the presence of blood was a good indicator of a violent event. Detective Gustave Mace of the French Surete showed that conclusively in 1869 while investigating the murder of an elderly craftsman. The victim’s dismembered body parts were found in a bag that had been dumped in a well. Mace’s attention soon turned to a man named Pierre Voirbo. He was a tailor who visited the building that used the well, bringing work to a female tenant. Mace soon became convinced that he had found his man. Upon investigating Voirbo’s living quarters, Mace uncovered items belonging to the victim. Mace also noticed that the rooms had been thoroughly cleaned recently, suggesting that the victim was dismembered there. Then, in a scene straight out of a murder mystery show, the detective noticed the floor was tiled unevenly. He dumped a jug of water on the floor to see where the liquid would flow. The water went into the channels between the tiles and ran into one area of the house. Mace pulled those tiles and uncovered a pool of dried blood beneath them.[3] The astonished Voirbo made a full confession and later committed suicide in prison.

7 The Rugeley Poisoner

The case of Dr. William Palmer (aka the Rugeley Poisoner) outraged Victorian England. Although the doctor stood accused only of the murder of his friend, John Cook, Palmer was suspected of also poisoning his own wife, his brother, his uncle, several children, and multiple patients. Cook’s father-in-law suspected foul play and had his body exhumed and examined. However, for some reason, the local coroner allowed Palmer to attend the autopsy as a professional courtesy. The doctor was able to sabotage the proceedings by bumping into the physician lifting the victim’s stomach, causing the contents to spill. Palmer was also suspected of breaking the seal on the jar where the remaining material was stored. The local authorities appealed to Alfred Swaine Taylor, the “father of British forensic medicine.” He concluded that the preserved samples were too degraded to yield accurate results. His own examination found only small, nonlethal traces of antimony. However, given the circumstances and symptoms surrounding Cook’s death, Taylor concluded that he had died of strychnine poisoning.[4] Taylor was brought in as a witness during the trial where the defense’s main strategy was to attack his credibility. Therefore, Taylor not only had to defend his expertise but also the field of toxicology as a whole. In the end, his expert testimony along with circumstantial evidence secured a guilty verdict. The Rugeley Poisoner was executed at Stafford Prison in 1856.

6 The Hand In Glove Case

In 1933, investigators in New South Wales used a bizarre technique to solve one of Australia’s most gruesome murders. On Christmas Day, the remains of a man were fished out of the Murrumbidgee River. His body was too decomposed to be identified. His left hand was mangled while the right one was missing entirely, eliminating the possibility of fingerprinting. While searching the riverbanks, detectives found what looked to be an old, dirty glove, except that it still had a thumbnail attached.[5] At the lab, they confirmed their suspicions—it was the missing right hand. Only the outer layer of skin was left as the flesh had been eaten by maggots. Investigators realized that, under perfect conditions, the hand could be used to obtain a fingerprint and maybe get an ID on the victim. The skin was treated carefully, and then a police officer used his own hand to slide inside it like a glove. This filled out the limp skin and actually created a usable print. Their victim was a vagrant named Percy Smith. Soon enough, police had a suspect—another drifter named Edward Morey who was found with the murder weapon. The case actually got weirder during the trial as the chief witness, Moncrieff Anderson, was gunned down in his home. His wife claimed that Anderson had been shot by an intruder and that he was the real killer of Percy Smith. Police soon realized that Lillian Anderson was in love with Morey and killed her husband to try to secure Morey’s release.

5 The Gouffe Case

In 1889, a French couple murdered an acquaintance named Toussaint-Augustin Gouffe, a bailiff from Paris. The woman, Gabrielle Bompard, attempted to seduce him while her partner, Michel Eyraud, strangled Gouffe with a noose. The couple was eventually identified, tried, and convicted. Nowadays, their case is primarily remembered for Bompard using the hypnotism defense, claiming she was under the spell of Eyraud. What is often forgotten is that the case was a landmark moment for forensic anthropology. Gouffe’s naked, badly decomposed body was found in a trunk abandoned near Lyon. While the trunk had several clues tracing it back to Paris, there were no indications as to the identity of the victim. Once the case fell under the purview of Paris Surete Superintendent Marie-Francois Goron, he appealed to Dr. Alexandre Lacassagne, the head of legal medicine at the University of Lyon. Lacassagne examined the skeleton and concluded that it belonged to a 50-year-old man who walked with a limp.[6] Gouffe was 49 and had a bad right knee. Meanwhile, Goron was investigating Gouffe’s disappearance in Paris. Both he and Lacassagne had a strong feeling that the missing bailiff was their trunk victim, but they needed definitive proof. Lacassagne asked for Gouffe’s comb, took a hair, and compared it with a corpse hair under the microscope. It was a match. His work, seemingly trivial today, showed the true value of forensics and formed the basis for the French school of criminology.

4 The Beekman Place Murder

Beekman Place might be one of Manhattan’s swankiest neighborhoods, but it is not immune from the depravity of mankind. In 1936, it was the location of the gruesome rape and murder of Nancy Titterton, the novelist and wife of high-profile NBC executive Lewis Titterton. Alexander Gettler was the man in charge of forensics. Despite the killer being very meticulous, Gettler found two pieces of evidence: a small line of cord pinned underneath Nancy’s body and a single strand of light-colored hair on the bedspread. After analyzing the trace evidence back at his lab, Gettler concluded that the hair didn’t belong to the victim. It was actually horsehair, commonly used for upholstery.[7] An examination of the cord revealed that it was low-quality Italian jute, 0.32 centimeters (0.13 in) wide. Police reached out to dozens of rope makers in the region and eventually matched it to a type of cord sold by the Hanover Cordage Company. Their product was also commonly used in the upholstery trade. Furthermore, their records showed that they recently had sold rolls of the cord to Theodore Kruger’s upholstery shop in New York. As it happened, Kruger delivered a couch to the victim on the day of the murder with his assistant, John Fiorenza. A background check revealed that Fiorenza had several arrests for theft and a state psychiatrist had labeled him potentially psychotic. During interrogation, Fiorenza caved and confessed to the murder. He was sentenced to death and executed in 1937.

3 The Almodovar Case

On the morning of November 2, 1942, a man walking his dog through New York’s Central Park stumbled upon the body of 20-year-old Louise Almodovar. She had been strangled with no obvious signs of sexual assault or robbery. Police found their primary suspect after talking to Louise’s husband, Anibal. She left him after just a few weeks of marriage because he refused to stop seeing other women. In return, he wrote her several hate-filled, threatening letters. Police were convinced that the former sailor was their killer, but there was one problem: Almodovar had a strong alibi. On the night of the murder, he had been partying with a girlfriend at the Rumba Palace in front of dozens of witnesses.[8] Detectives believed that the club was close enough to the crime scene for Almodovar to have time to sneak out, kill his wife, and return without anybody noticing. They needed evidence, so they appealed to Alexander Gettler again. In turn, Gettler turned to colleague Joseph J. Copeland, who applied his extensive knowledge of botany to forensics. The clothing worn by Almodovar on the night of the murder had some grass seeds on them which Copeland traced to Central Park. In a previous statement, the husband said that he hadn’t been to Central Park in years. But now he claimed that he had taken a stroll through the park about two months earlier. Copeland again caught him in a lie as the grass in question was a late bloomer, not found in early September. The forensics placed Almodovar at the scene of the crime, and he eventually confessed to killing his wife.

2 The Siskiyou Train Robbery

In America, some of the earliest forensic work was done by Professor Edward Heinrich. None showed off his talents, as well as the value of forensics, better than the Siskiyou train robbery. On October 11, 1923, Roy, Ray, and Hugh DeAutremont attempted to rob the Oregon-California Express passing through the Siskiyou Mountains. They ended up using too much dynamite, which caused too much damage to the mail car. During the botched heist, the brothers killed four people, wanting to leave no witnesses. What followed was the largest, most expensive manhunt in US history at that point. Police found a nearby cabin full of items showing that it was the location where the robbers had planned their heist. It contained clothes, guns, ammo, and materials used in explosives. But there was nothing to allude to their identities. Police sent the evidence over to Professor Heinrich to see if he could come up with anything. Recently disclosed documents show us just how much information Heinrich was able to provide using forensics. Examination of dust, fibers, and stains on a pair of overalls showed that it belonged to a lumberjack working in a fir or spruce camp.[9] He was, at most, 178 centimeters (5’10”) and 75 kilograms (165 lb), aged between 21 and 25, and lefthanded. Heinrich also performed tests involving ballistics, fingerprints, blood, hair, cartridges, and handwriting comparisons. Eventually, he used serial number restoration to link a .45 caliber gun to Ray DeAutremont. Soon afterward, Los Angeles opened the first police crime lab in the country.

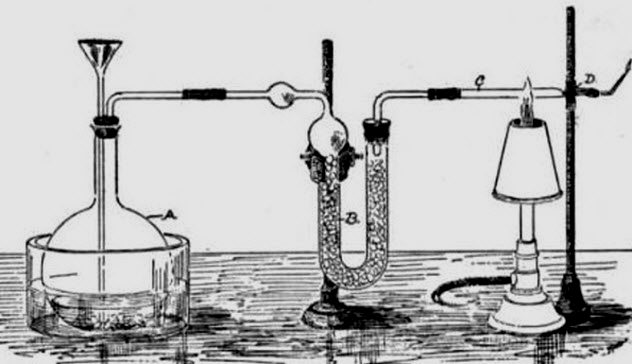

1 John Bodle

Undoubtedly, one of the greatest breakthroughs in toxicology that helped to establish the field as a valuable part of forensics was the development of the Marsh test in 1836. Back then, arsenic was the favored weapon of the poisoner because it was odorless, easy to obtain, and almost untraceable in the body. Some rudimentary tests were developed by Samuel Hahnemann and the aforementioned Valentin Rose, but they were not sensitive enough to guarantee results. This changed in 1832 when a man named John Bodle stood accused of killing his grandfather by poisoning his coffee with arsenic. Chemist James Marsh was brought in to consult on the case. Even with the primitive tests available at the time, Marsh was still able to confirm the presence of arsenic. However, because the resulting precipitate was unstable, it had deteriorated by the start of the trial and Bodle was acquitted.[10] Angered by the result, Marsh started working on a better test for arsenic. Four years later, he presented his new, eponymous test. It received attention and acclaim almost immediately as it was used in the highly publicized Lafarge poisoning case. The Marsh test was far more accurate than its predecessors, being able to detect as little as 0.02 milligrams of arsenic. It had its fair share of problems, such as antimony giving a false positive. But improvements were made over the decades, and the Marsh test became the new industry standard.