There are museums that actually display these body parts. Many of them belong to famous people, and the stories behind them are usually out of this world. And ouch! They include private parts, too. Two privates actually—one long and one short. Here we go.

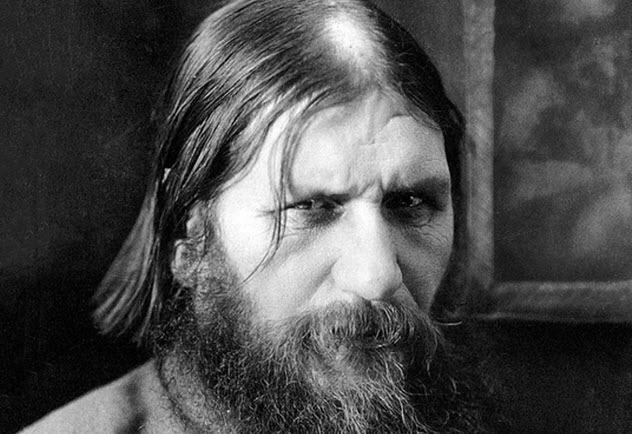

10 Grigori Rasputin’s Penis

Grigori Rasputin was a faith healer and adviser to the ruling Romanov family of Russia before he was assassinated in 1916. He was a very curious character, and the only thing more peculiar than his personality was his 33-centimeter-long (13 in) penis that presently lies in the Museum of Erotica in St. Petersburg, Russia. According to his daughter, Marie, 33 centimeters (13 in) was the length of her father’s penis when it was flaccid and it was much longer when at attention. For comparison, the average penis length is 9.2 centimeters (3.6 in) when flaccid and 13.1 centimeters (5.2 in) when erect. How the penis went missing remains a mystery. One account says that Grigori’s assassins cut it off and a maid who came to clean his room the next day was so impressed with what she saw that she took the penis away. Another account states that one of Grigori’s former mistresses took his penis as a souvenir during his autopsy. Later, Marie got her hands on her father’s penis, but it went missing after her death in 1977. It reappeared again when one Michael Augustine tried selling it to an auction house. However, that penis was found to be a dried sea cucumber. The real thing eventually appeared in the hands of a French collector who sold it to a Russian doctor in 2004. It was the doctor who took it to the museum where it is displayed among other sex items.[1] To be clear, though, there are claims that the penis at the museum does not belong to Rasputin or even a human for that matter. Nevertheless, that does not change the fact that there is a 33-centimeter-long (13 in) penis in a Russian museum.

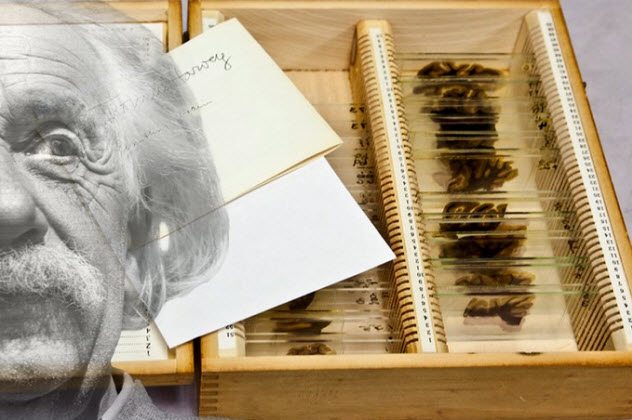

9 Albert Einstein’s Brain

Part of Albert Einstein’s brain presently lies in the Mutter Museum in Philadelphia. Einstein never wanted his brain to be kept in a museum. He actually requested to be cremated after his death to prevent anyone from creating a cult around him. However, after Einstein’s death on April 18, 1955, pathologist Thomas Harvey removed—or rather, stole—the physicist’s brain and eyeballs. Later, Einstein’s family allowed Harvey to keep the brain on the condition that it would only be used for scientific purposes. With the aid of lab physician Marta Keller, Harvey cut Einstein’s brain into 1,000 slices, put them on glass slides, and sent them to several pathologists. Dr. William Ehrich of the Philadelphia General Hospital got 46 of these slides. After Ehrich’s death, his wife passed them to Dr. Allen Steinberg, who gave them to Dr. Lucy Rorke-Adams. It was Rorke-Adams who donated these slides to the museum. Close to 350 of the slides also lie at the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Maryland.[2] Einstein’s brain is just one of the many body parts kept at the Mutter Museum. They also have the fused livers of Chang and Eng Bunker (the first conjoined twins), the corpse of a Philadelphia woman called the Soap Lady (due to the waxlike consistency of her remains), and a diseased 2.7-meter-long (9 ft) colon with 18 kilograms (40 lb) of feces. Little wonder that visitors are usually advised not to eat before visiting.

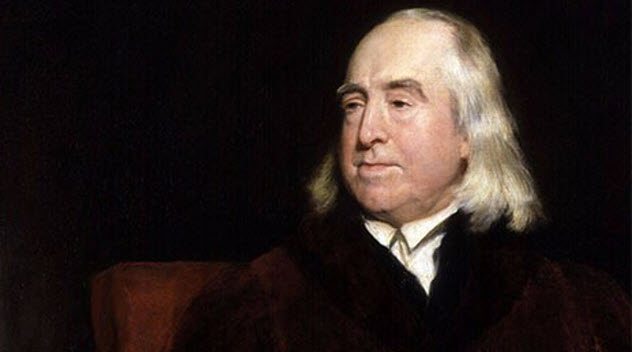

8 Jeremy Bentham’s Head

Jeremy Bentham was an eccentric philosopher who lived from 1748 to 1832. When we say eccentric, we mean that he was the kind of man who called his cat The Reverend Sir John Langbourne. Bentham also asked that his body be preserved after his death so that he could attend his friends’ parties. True to Bentham’s wishes, his body was preserved after his death and remains on exhibit at a museum at University College London. However, his real head has been separated from his body and replaced by a wax model. Bentham might be eccentric but not to the extent of requesting that his head be separated from his body. His real head was removed after the embalming went wrong. Bentham requested that his head be embalmed with the same method used by the Maori people of New Zealand. However, his friend Dr. Southwood Smith—who did the embalming—was not familiar with the process and the head ended up in a terrible state. So, it had to be removed. The head used to be displayed in the museum, but it was placed in storage in the 1990s after being stolen by students from a rival university.[3]

7 Galileo Galilei’s Tooth And Fingers

Famous astronomer Galileo Galilei died in 1642. In 1737, his body was being relocated to a new tomb opposite that of Michelangelo in Florence, Italy, when some of Galileo’s fans seized the opportunity to steal three of his fingers, a tooth, and a vertebra. One of the fingers ended up at the Museum of the History of Science in Florence, Italy. The remaining fingers (a thumb and middle finger) and a tooth were privately held by a family.[4] The parts held by the family went missing in the 20th century but somehow showed up again in 2009. Not wanting to lose track of Galileo’s parts again, the Museum of the History of Science acquired the fingers and tooth and now exhibit them alongside the third finger. The museum was also renamed the Galileo Museum. They have more body parts of Galileo than anyone else. Meanwhile, Galileo’s vertebra remains at the University of Padua.

6 Antonio Scarpa’s Head

Antonio Scarpa was an Italian anatomist and neurologist who died on October 31, 1832. Before his death, he worked at the University of Pavia where he made more enemies than friends. He was an arrogant fellow who was famous for spreading rumors about others. He was also a nepotist who only offered jobs openings at the university to his friends and illegitimate children. Scarpa’s autopsy was conducted by Carlo Beolchin, a former assistant who removed Scarpa’s head, thumb, index finger, and urinary tract. No one knows the exact reason why Beolchin removed Scarpa’s parts.[5] Some say that Beolchin saved these body parts for future generations. But considering Scarpa’s ruthlessness, Beolchin could just as well have removed them to get back at his former boss. Rivals who could not get their hands on Scarpa’s parts defaced a marble statue erected in his honor. Except for the head, Scarpa’s parts were kept at an Italian museum. The anatomist’s head was initially hidden but eventually reappeared years later when it was displayed at the Museo per la storia dell’Universita di Pavia (Museum of the Story of the University of Pavia). The museum is now in possession of Scarpa’s other parts but has decided to keep them in storage.

5 Charles Babbage’s Brain

Charles Babbage invented the modern computer and is regarded as the “father of the computer.” Today, one-half of his brain lies at the Science Museum in London while the other half lies at the Hunterian Museum inside the Royal College of Surgeons in London. Unlike Einstein, Babbage actually wanted his brain to end up somewhere other than inside his skull. Before he died in 1871, Charles wrote a letter to his son Henry in which Charles detailed his wishes about his brain. Charles clarified that he had no qualms about his brain being removed and preserved after his death provided that it was used to promote the cause of science. In the letter, Charles told Henry that he wanted his brain “disposed of in any manner which [Henry considered] most conducive to the advancement of human knowledge and the good of the human race.”[6]

4 Napoleon Bonaparte’s Penis

Napoleon Bonaparte’s defeat at the Battle of Waterloo was the beginning of his end. First, he lost the French throne. Second, he was captured by the British and exiled to the island of St. Helena where he died under mysterious circumstances in 1821. Third, he lost his penis during an autopsy to determine what killed him. Dr. Francesco Autommarchi, who performed the autopsy, removed Napoleon’s penis—which is said to be just 3.8 centimeters (1.5 in) long—in the presence of 17 people. Autommarchi gave the little member to Abbe Anges Paul Vignali, the priest who gave Napoleon his last rites. A book collector purchased the penis in 1924 before it was sold to someone in Philadelphia. In 1927, the penis was displayed at the Museum of French Art in New York.[7] A Time magazine journalist who saw the penis at the museum referred to it as “a maltreated strip of buckskin shoelace.” The penis was later sold at auction to John J. Lattimer in 1977 and has remained with the Lattimer family ever since.

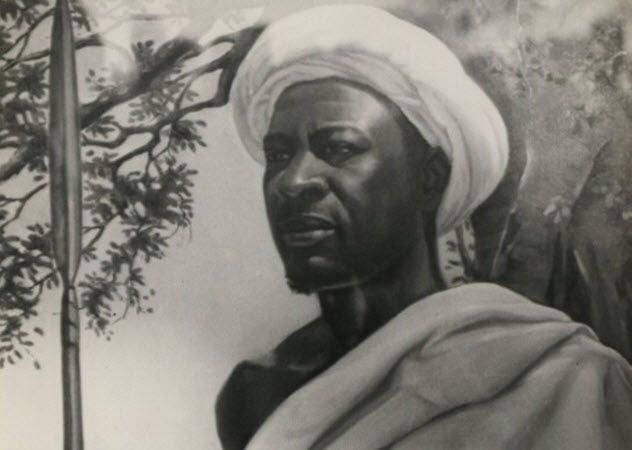

3 Chief Mkwawa’s Skull

Chief Mkwavinyika Munyigumba Mwamuyinga (aka Chief Mkwawa) is remembered for fiercely resisting the German invasion and colonization of Hehe tribal lands in today’s Tanzania. In 1891, he rebelled against the German colonists and even killed a top German official in battle. Germany finally captured the Hehe villages and forts. But they still couldn’t capture Chief Mkwawa, who fought back using hit-and-run tactics. In 1898, Chief Mkwawa shot himself in the head after he was surrounded by Germans troops. But the Germans weren’t letting him off that easily. They removed his skull and sent it to Berlin.[8] During World War I, the Hehe fought on the side of Britain against Germany. As we all know, Britain won the war. To show their appreciation for the Hehe’s efforts, the British included a clause in the 1919 Treaty of Versailles that ordered Germany to return Chief Mkwawa’s skull to the Hehe. However, Germany could not account for the skull so the Hehe got nothing. After World War II, Sir Edward Twining, the governor of Tanganyika, revived attempts to retrieve the skull. He traced it to Bremen Museum in Germany. There, he found 2,000 skulls, 84 of which were from Tanzania. Only one had a bullet hole in the head, so Twining assumed that it belonged to Chief Mkwawa. The skull is presently displayed at the Mkwawa Memorial Museum in Kalenga in Tanzania.

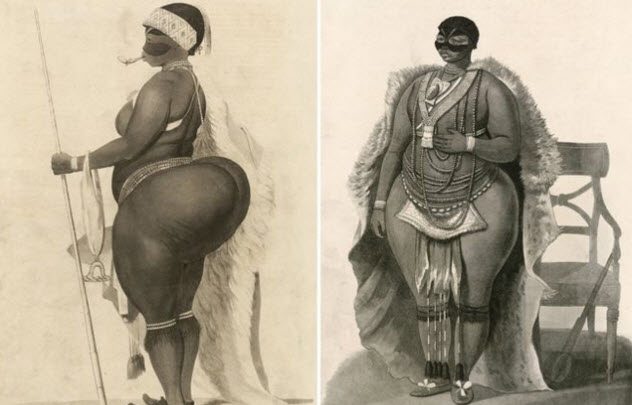

2 Sarah Baartman’s Brain And Genitals

Sarah Baartman was born in Eastern Cape, South Africa, in 1789. She had a medical condition called steatopygia, which caused an abundance of fat in her buttocks. This caused her buttocks to be bigger than normal, and it often generated curiosity. In October 1810, she signed some paperwork—despite being illiterate—that permitted surgeon William Dunlop and her boss, Hendrik Cesars (in whose house she worked as a maid), to ship her off to be exhibited in England. There, Baartman was exhibited under the stage name “Hottentot Venus.” During her performances, she often wore beads, feathers, and tight clothing in the same color as her skin and smoked a pipe. She traveled to Paris in 1814 and died there a year later. After her death, naturalist Georges Cuvier dissected her. Baartman’s brain, skeleton, and genitals were exhibited at the Paris Museum of Man until 1974. After the request of President Nelson Mandela in the mid-1990s, Baartman’s remains were finally returned to South Africa in March 2002. She was reburied in Hankey.[9]

1 Mata Hari’s Skull

Mata Hari was one of the top spies of the 20th century, even though whom she spied for remains a hotly debated topic. Possible candidates include France, Germany, or both. Nevertheless, she was executed by France on October 15, 1917, for spying for Germany during World War I. Some believe that France only used Mata Hari as the proverbial scapegoat to explain their losses during the war. She was a professional prostitute with connections to top German officials, which made her the perfect scapegoat. Mata Hari’s remains went unclaimed after her execution and were sent to the school of medicine in Paris to be used for anatomy studies. Her head was removed at the school and was kept at the Museum of Anatomy where it mysteriously went missing.[10]