But the revolution wasn’t all positive. Thousands of innocent people lost their lives and the country was torn between different groups who used force to crush rebellion. It led France into dictatorship and, eventually, back to the days of kings. Here, we’ve rounded up ten of the most dreadful atrocities of the French revolution. Top 10 Pretenders to the Thrones of Europe

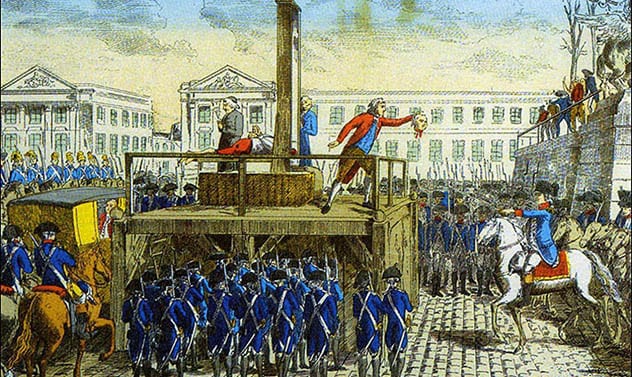

10 Beheading Louis XVI

The beheading of Louis XVI and his wife Marie Antoinette was one of the biggest events of the French Revolution, but it didn’t have to happen. Before he was king, Louis XVI was quiet, dedicated to his studies and painfully shy. It took him seven years to consummate his marriage to the beautiful and intimidating Hapsburg heiress. When he became king he was cautious and indecisive, eager to be loved. In another age he would have been a great king, but he was entirely unsuited to the political crisis of the time. People around him took advantage of his weakness to seize more power. Louis was little more than a figurehead. It was no surprise when the new government voted to abolish the monarchy shortly after. Some revolutionaries argued against executing Louis, but the revolution was in full swing and the public hated him. Louis XVI was killed by guillotine in January 1793. The move shocked many across the world since Louis had always been seen as a moderate king. His death enraged nearby European countries and led to a war that might have been avoided. He faced his death fearlessly: with his final breath, he forgave those who condemned him and hoped that no more blood would be spilled.[1]

9 Toppling Of Statues

Executing Louis wasn’t enough: later that year, the rebels decided to remove all trace of the old kings from the country. They started with the tombs of St Denis, the traditional resting place of France’s royals. To begin with, the masons were happy just to destroy the old Carolingian statues and other symbols of royalty. But within a month they were hammering into the old vault that held the kings from the House of Bourbon. When they were in, they started destroying the old coffins. Some of the kingly remains were put on public display, while others were dumped into a large burial pit, to cries of joy from the crowd. Many people came to watch—so many that the labourers struggled to do their work. According to eyewitnesses, members of the crowd grabbed at the bodies when they could, taking stray hairs, teeth and other things as personal mementos. These acts were later condemned both within France and across the world, but by that time it was too late. After the Bourbon Restoration, the kings were retrieved from the pit and moved to the crypt in the basilica, but the damage was already done: many of the kings were unrecognisable.[2]

8 The Law of Suspects

The revolution started because the rebels wanted everyone to be free and equal. After they won, though, their anger didn’t come to an end: instead, they started hunting down anyone who might be a threat. This period is now known as the Reign of Terror, and it resulted in thousands of innocent deaths. The Reign of Terror started with the Law of Suspects, which granted the government the power to accuse pretty much anyone of being a rebel. They attacked the priests, who were driven underground—for a while, being Catholic was actually illegal. In the end, anyone who might have been connected to the old nobles could be imprisoned and executed. Over two years around 500,000 people were accused—a huge number for the time. So many were accused, in fact, that the prisons were too full and people had to be put under house arrest. Though most were eventually allowed to walk free, around 16,000 people were killed—and many thousands more died in prison. Under the law, anyone whose “conduct, relations or language [showed them to be] partisans of tyranny … and enemies of liberty” was arrested and put on trial.[3]

7 Lyon Erased

Not everyone in France supported the revolution. The city of Lyon backed the moderate Girondins, a group who were part of the revolution but were not as bloodthirsty as the others. The rebel leaders considered Lyon a centre of royalist support, so they laid siege to it in 1793. Over the course of the fighting over 2,000 people were killed in Lyon and the city was conquered. The revolutionaries had won, but they had further plans for the city. In October, the National Convention issued a decree calling for Lyon to be destroyed. Everyone who lived in Lyon was to have their weapons taken away. They would be given to revolutionaries. Any building “inhabited by the wealthy” was to be torn down, leaving only the homes of the poor, factories, and some monuments. They even planned to purge the city’s name from history. The city’s name would be erased: Lyon would be called Liberated City (Ville Affranchie) instead. They planned to build a column with an inscription on it saying: “Lyon made war on Liberty; Lyon is no more.” Fortunately, this project was never finished.[4]

6 Girondins Executed

France’s new government had two main groups: the Girondins and the Montagnards. The Girondins were moderates: they wanted to build a free, capitalist, democratic country where everyone had a say in how they were ruled—regardless of who they were. They were supported across France but the people of Paris liked the Montagnards more. They were extremists who “wanted everything levelled”. Anyone seen as elite had to give up their status or be executed. The groups got along well to begin with, but fell out over Louis’s death. The Montagnards wanted to kill him, but the Girondins wanted the country to vote on it. The Montagnards said they were plotting to save the king and called them traitors. Things boiled over on the streets of Paris. A group of soldiers and citizens surrounded the government buildings and demanded the Girondins be kicked out of the government. The Montagnards duly did so. Some Girondins were able to escape, but a few months later, those who were left were rounded up and guillotined.[5] 10 Real Countries Straight Out Of The Handmaid’s Tale [DISTURBING]

5 Drownings at Nantes

The city of Nantes was a center of revolution, but much of the countryside surrounding it was royalist. The region rose up in rebellion, leading to the Battle of Nantes. After this, the new French government decided to purge the city of anyone who still supported the monarchy. To do this, they sent Jean-Baptiste Carrier, one of their most committed supporters. Jean-Baptiste took his job very seriously. In around five months, between 12,000 and 15,000 people were killed by his order. Nantes lies on the Loire, which Jean-Baptiste called “the national bathtub”. He and his men built special boats called lighters which were specifically designed for drowning prisoners. The captives would be shackled to each other, often naked, and herded onto the boats—which had trap doors on the bottom. The boats were then sunk with the prisoners on board. The elderley, pregnant women and children were all drowned without distinction. In the end Jean-Baptiste’s methods were too extreme even for the revolution: he was recalled to Paris by the Committee of Public Safety, put on trial and executed by guillotine.[6]

4 Law of 22 Prairial

Over the course of the Reign of Terror, thousands of people were imprisoned, some for absurd reasons. By June 1794, the prisons of France—particularly Paris—were overcrowded, so action had to be taken. Robespierre and his allies drafted a new law which would allow trials to be concluded much quicker: they pushed this law through the Convention and it was passed on 10 June 1794. It meant that people could be put on trial for simple things like ‘spreading fake news’ or ‘seeking to inspire discouragement’. Citizens were expected to confront or report their neighbours if they expressed any kind of opposition to the government. When these people were put on trial, they weren’t treated fairly: the judges and jury only had three days to come to a conclusion, and they had to choose whether to allow the accused to go free or be put to death. This new law marked the beginning of the Grand Terror. Executions per day increased dramatically across France, and most of those killed were undoubtedly innocent. The Grand Terror came to an end after two months, but not because people were horrified by the killings. No, the new law had also made it so members of the Convention could now be put on trial. Looking to preserve their own skins, the members of the Convention removed Robespierre and guillotined him, bringing an end to the killings.[7]

3 The Massacre in the Vendee

The revolution was supposed to be a movement that freed the French lower classes and gave them liberty and security. But anyone who opposed the new government was harshly punished, even those who were lower class. In the early days, the church was singled out for its wealth and excess. The revolutionary government veered between atheism and a new state religion, the Cult of the Supreme Being, but they were united in their desire to destroy the old Catholic system. In the Vendee, however, the people rose up to protect their priests and churches from the new revolutionary government. When the government ordered them to form a conscript military unit, they rebelled, joining together in local militias which were collectively known as the Catholic and Royal Army. This alarmed the new government, who sent the army to tackle the problem. After a series of pitched battles, the Catholic and Royal Army was defeated. But the government didn’t stop there. Determined to prevent another such uprising, the government sent General Louis Marie Turreau with twelve columns of troops to destroy to Vendee. Farms, villages, supplies and forests were destroyed, and the soldiers killed without restriction. When it was over, General Francois Joseph Westermann wrote a letter back to the government saying: “There is no more Vendée… According to the orders that you gave me, I crushed the children under the feet of the horses, massacred the women who, at least for these, will not give birth to any more brigands. I do not have a prisoner to reproach me. I have exterminated all.”[8]

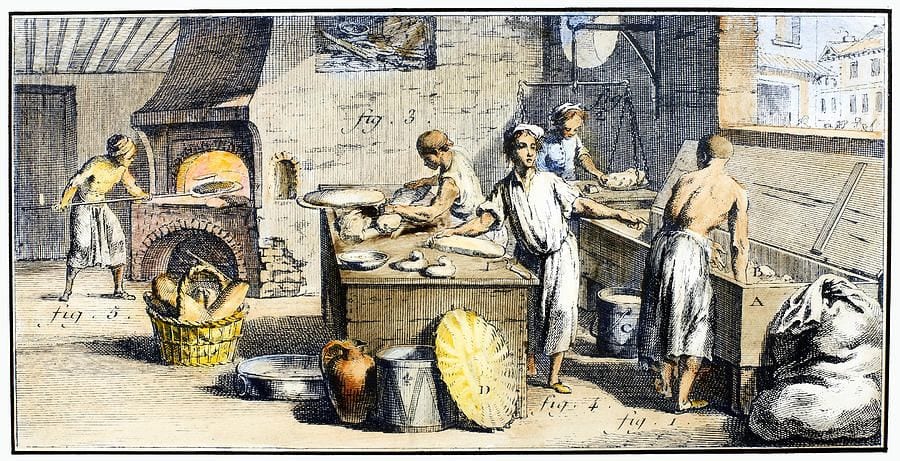

2 Law of the Maximum

Unlike many other atrocities on this list, the Law of the Maximum was implemented with good intentions—though the government was forced to do it. One of the biggest reasons people joined the rebellion in the first place was because food was too expensive, but by 1793 even the basics were going back up in price. The enrages, a collection of anti-elite protestors who might today be called Marxists, argued that the nobility had been replaced by greedy merchants. Action was needed to take away their wealth and help the poor. The government passed the Law of the Maximum in response. It set a maximum price for goods, from bread and wine to iron and shoes. Merchants had to display a list of prices outside their stores and, if any of their prices were above the maximum, they would be fined. Instead of going to the government, the fine went to whoever informed the authorities about the illegal pricing, encouraging people to rat out merchants who ignored the law. It had a disastrous impact on France. While merchants did reduce their prices, it left them with almost no money. The less honest shopkeepers began watering down their goods, disguising ash as ground pepper, starch as sugar and pear juice as wine. Farmers in rural areas began hoarding their produce because they couldn’t get a good enough price in the cities, meaning that people in the cities starved. The result was a black market where the rich could still buy the goods they needed, while the poor had no access to food at all. These famines were fixed temporarily when the government sent soldiers to take food from the farmers and bring it to the city by force, but this only caused more unrest.[9]

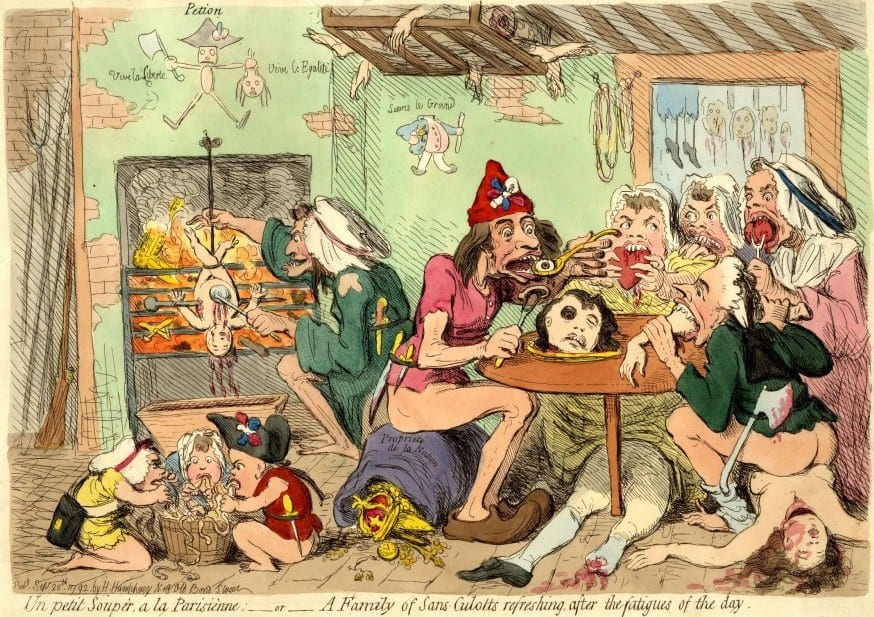

1 September Massacres

After Louis was killed, the government fell into chaos. No-one knew who was in charge. In the meantime the Paris Commune, who were supported by the armed mob, had all the power. Chaos reigned as the new government fought over who should be in power, alongside issues like the economy, the army, and the justice system. What dominated, however, was a fear of counter-revolutionary backlash. The new movement had been denounced in Britain, Austria and Prussia, and war loomed on the horizon. Meanwhile, French royalists were gathering support in other parts of the country. The revolutionaries feared that, if a royalist army was to attack Paris, the new revolutionary government would fall. In particular, they came to believe that the inmates of the city’s prisons would join with the counter-revolutionaries if given a chance. These fears were exacerbated when it came time for the new army to leave the city, with the people believing it would leave the city vulnerable to a prison break. Between the 2nd and 6th of September 1792, the inmates were attacked by revolutionary mobs, with over 1000 being killed in the space of a single day. Half the city’s entire prison population was massacred, with corpses left mutilated in the streets. The revolutionary government sent letters to regional governments saying that conspirators in the city’s prisons had been executed. The act was repeated elsewhere: murders of prisoners took place in 75 of France’s 83 departments.[10] 10 Things We Owe To The French Revolution