They brought new surprises in animal behavior, looks, and evolution. Some were just plain bizarre, while others, millions of years old, gave first-time looks at rare soft tissues and death a little too fresh.

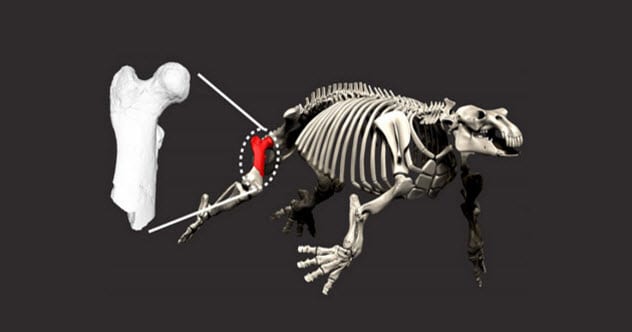

10 The Forgotten Bone

In 2017, a museum curator found a forgotten box at a Japanese university. Inside was a dinosaur femur and a note carrying the name of its discoverer. Curious about the species and the history behind the original discovery, a new analysis was done. It shattered the decades-old belief that it belonged to a dinosaur. Instead, the femur came from an extinct water mammal. Resembling a cross between a manatee and hippo, it cruised the Pacific Ocean 15.9 million years ago. The herbivore, which belonged to the extinct genus Paleoparadoxia, grew up to 2 meters (6.5 ft) in length. The specimen’s age confirmed something scientists already knew—that Paleoparadoxia inhabited the seas 10–20 million years ago.[1] However, this particular bone showed muscle scars. Such lines depict how a muscle is used during the animal’s lifetime, and they could reveal how this creature moved its back leg. Ironically, the villager who found the femur knew it was not a dinosaur bone. During an interview, he even knew that it belonged to the extinct order of aquatic mammals called Desmostylia. Clearly, he had shown it to a scientist, but the latter had never pursued the matter. It was packed away and forgotten as an uncataloged “dinosaur” bone.

9 A Proto-Mammal Litter

A couple of million years ago, a mammal gave birth to a huge litter of 38 babies. Well, it wasn’t exactly a mammal. Kayentatherium wellesi was a cynodont, a mammal relative that lived during the Jurassic. The hairy creature was about the size of a beagle and offered interesting evolutionary insights. The 2018 study looked for links between the unique fossils and modern mammals. The 185-million-year-old litter was twice the size produced by any species today. This trait was more suited to reptiles. The babies also differed in another crucial way. Most young mammals today are cute, thanks to big heads and short faces. However, the bulbous skulls are not made to look adorable but to hold big brains. The ancient infants had brains so small that they were born with skulls needing little structural transformation. Their 1-centimeter-long (0.4 in) heads were exact replicas of the adult female’s. For researchers, this is a once-in-a-lifetime discovery because it shows the lack of an important evolutionary step. At some point, mammal litters shrank as their brains grew. The hairy wonder and her large family proved that this had not yet happened during the Jurassic.[2]

8 The Platypus Fish

Around 175 million years before dinosaurs even existed, there was a magnificent coral reef near Australia. It was home to the earliest reef fauna, and the dominant fish group was placoderms, jawed vertebrates often plated with armor. In 2018, researchers decided to reconstruct a species called Brindabellaspis stensioi. Using fossils up to 400 million years old, the study revealed the strangest fish of the region. Apart from having nostrils in its eye sockets, Brindabellaspis had a bizarre skull. Among other things, the jaws resembled the snout of a platypus. The armored fish likely cruised the seafloor, much like a stingray looking for the electrical signals of prey hiding in the mud.[3] This conclusion came after a surprising discovery. The snout was lined with a sensory system, and soon, scientists recognized that it was a modified version of the pressure sensors that exist in other fish. It is a pity that placoderms are all extinct as a living specimen could have solved another sticky mystery. Brindabellaspis is so weird that nobody knows how or where it fits into the scheme of things.

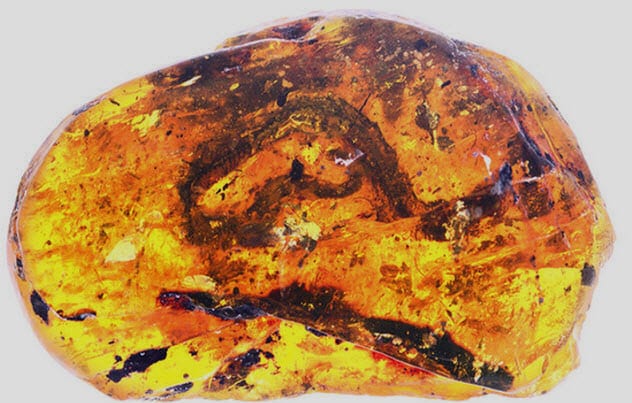

7 Unique Snake

Approximately 99 million years ago, a baby snake died shortly after it hatched in Southeast Asia. Tree resin flowed over the newborn, and over time, the goo turned into amber. The immaculately preserved reptile (albeit missing its head) ended up in a private collection. In 2018, it became available for scientific study in China. There were a few surprises. The hatchling was confirmed as the oldest baby snake ever found. Alongside the tiny record holder was a scrap of skin. It belonged to an adult snake, although it was too small to say if they belonged to the same species.[4] The baby’s 97 vertebrae pegged it as an unknown type of snake. Near the top of each vertebra was an unknown structural design unique among snakes. Called Xiaophis myanmarensis, it was also among the most primitive of the snake family. The question of where it lived was answered by the bugs and plants trapped inside the amber, revealing that Xiaophis lived in a forest habitat.

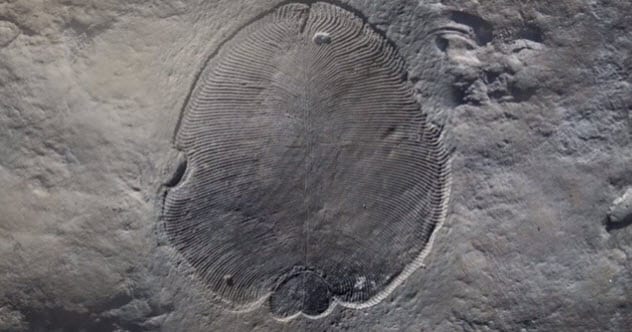

6 World’s Earliest Animal

For decades, a bizarre blob fractured the scientific community. Discovered in 1947, the so-called Dickinsonia fossils had flat, oval bodies up to 1.4 meters (4.6 ft) long. Another confusing feature was the heavily ribbed look. Nobody could agree if this was a plant, animal, fungus, or even a colony of some kind. In 2018, a daring effort was made to identify the 558-million-year-old creature. To perform a more conclusive analysis, a fossil with organic matter had to be found. A frosty fossil bed in Russia was chosen, but samples had to be mined from a high cliff while dangling on a rope. The effort paid off. Dickinsonia fossils were found, and cholesterol was inside one remarkably preserved specimen. The fat molecules not only revealed that the ribbed blob was the planet’s earliest animal but also proved that animals could become big and plentiful millions of years before anyone believed it was possible.[5]

5 Alive-Looking Snail

In 2016, researchers purchased a piece of amber from a private collector. Frozen inside the ancient resin was something paleontologists thought they’d never see—two snails. At 99 million years old, they were the oldest snails ever found in amber. One in particular was a showstopper. It was so well-preserved that it looked alive.[6] The creature’s body posture suggested a harrowing end. The snail was stretching forward with a cloud of bubbles around its head, capturing the very moment it died. As the tree resin began to engulf the snail, it tried to get away but failed. Once the creature was fully engulfed, air escaped, probably from a lung, and gathered around the head. This is the first glimpse of a prehistoric snail’s soft tissues. It helped identify the creature as a possible ancestor of the living Cyclophoridae family of snails, the oldest cyclophoroideans in Asia.

4 Oldest Dandruff

In 2018, scientists investigated the petrified remains of a 125-million-year-old dinosaur when they found fossilized flakes on its skin. It turned out to be the world’s oldest dandruff. The bad hair day—or in this case, feathers—came from a microraptor the size of a crow. The predator had four winged limbs but used them for something other than flight. The flakes consisted of corneocytes, cells full of the protein keratin. Today’s birds have corneocytes with loosely arranged keratin, and the cells are also very fatty. This design cools birds after flight. The microraptor’s dandruff had no fat, suggesting a failure to adapt to an airborne lifestyle.[7] Two other genera, Beipiaosaurus and Sinornithosaurus, were recovered from the same rocks in northeastern China. Both also had dandruff. Although plumage was only starting to evolve during this time, the three specimens showed how dinosaurs had already adapted their skin to a very modern feature (feathers). The flakes are also the only proof that dinosaurs shed their skin as dandruff and not in sheets or as a single piece like reptiles.

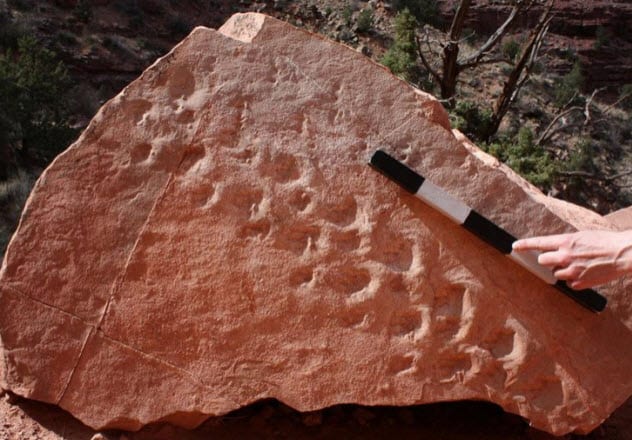

3 Bizarre Movement

In 2016, a paleontologist was hiking in the Grand Canyon with students when they found 28 tracks. The footprints were 310 million years old, making them the most ancient in the Grand Canyon. The creature responsible walked in a bizarre manner. The tracks showed an unusual diagonal gait, with steps pointing 40 degrees away from the main trail. The animal almost appeared to sidestep to a line dance. Possibly, a strong wind pushed the animal sideways as it tried to walk forward. Another theory suggests that the animal tried to steady itself while moving across a dodgy surface, like a dune. The odd gait remains as much a mystery as the species it belonged to. Researchers could only glean that the creature was reptilian and had four legs.[8] However, the tracks resemble 299-million-year-old prints found in Scotland during the 19th century. Back then, the Scottish fossils were loosely called Chelichnus by way of a group classification. If analysis could link them to the Grand Canyon dancer, the latter might also prove to be the oldest of this enigmatic group.

2 Bird Lungs

When scientists recently unearthed a fossil in China, it was an exciting moment. The creature was called Archaeorhynchus spathula, a tiny bird that lived 120 million years ago. Only four others had ever been found. It was also the only one with excellently preserved feathers, revealing a tail feature (common in modern avians) seen for the first time in Mesozoic birds.[9] During analysis, something came to light that trumped the bird’s rarity. The chest area showed a white-speckled lobed structure that was fossilized lungs. Soft tissue rarely survives millions of years, but researchers are positive that the lobes are lungs. Their shape, location, and breathing features were surprisingly like the respiratory system of modern birds. Several samples taken from the lungs also showed similar air capillaries and cells. When the great dinosaur extinction event happened 66 million years ago, many avians also became extinct. However, the lineage of Archaeorhynchus spathula survived. The bird’s advanced physical traits were probably the reason why.

1 Oldest Nervous System

Chengjiangocaris kunmingensis was a shrimplike creature that lived in South China half a billion years ago. Recently, a couple of complete fossils were found, and through some, a curious line ran the length of the body. A closer look revealed something astonishing—the line was a preserved nerve cord. Fossilized soft tissue remains rare, but this was the jackpot. Not only was it the most ancient nervous system ever recorded but it was also the best preserved. Researchers have never seen anything like it. Clusters of nerve tissue gave the cord a “beaded string” look. These clumps became smaller along the central cord the closer they sat to the tail. In addition, they were each linked to a pair of legs. Interestingly, the legs shrank in size the nearer they progressed to the back of the creature.[10] C. kunmingensis was an ancestor to arthropods (insects, arachnids, and crustaceans). However, its unique nerves more closely resembled those of modern worms. A similar design exists in living arthropods but carries fewer nerves. The reason for this reduction is not fully understood. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages