Evolution has driven them into bizarre shapes. Here are 10 of the weirdest, creepiest fungi that you might not want to find if you go down to the woods today.

10 Dead Man’s Fingers

Many fungi live unseen beneath the soil for most of the year. The only time you see them is when they poke up their spore-producing structures. Mushrooms are just the way that fungi spread their descendants. Not all fungi produce mushrooms, however. Xylaria polymorpha, commonly known as dead man’s fingers, sends up branches of gnarled-looking black structures. Their common name is apt because they look as if they could well be the fingers of some dead man trying to scratch his way out of the earth. The black surface is the spore-producing part of the fungus, which lives on the decaying matter of plants beneath the surface.

9 Devil’s Tooth

Hydnellum peckii goes by many common names: bleeding-tooth fungus, strawberries and cream, red-juice tooth, and Devil’s tooth. All refer to the shocking appearance of the fungus. From the top of the cap, a vivid red fluid is exuded. The fungus lives with pine trees, attached to their roots, and helps them to gain nutrients from the soil. This is a common strategy, and many plants exist in a symbiotic relationship with fungi. The fine strands of the fungi can penetrate more efficiently into the soil than roots. The plants provide the fungi with sugars, and the fungi offer mineral nutrients in return. No one is certain why the fungus produces the bloodlike substance. Analysis of the fluid has found that it contains atromentin, a chemical with anticoagulant properties. So the bleeding-tooth fungus could be effective in making you bleed.

8 Common Stinkhorn

Phallus impudicus is a Latin name meaning “shameless penis.” One look at the structure which sprouts from an underground “egg” is enough to explain why it got that binomial. The common stinkhorn can grow up to 25 centimeters (10 in) in a matter of hours—shameless indeed. The stinkhorn is another perfectly natural name for it. The “horn” does stink. The tip of the fruiting body is covered with a smelly, sticky substance. The stench attracts flies that walk all over the end of the structure, picking up spores as they do so. Etty Darwin, Charles Darwin’s granddaughter, was so traumatized and disgusted by the shape of the stinkhorn that she would get up before dawn to hack down any that she found.

7 Ink Cap

The common ink cap begins as a dull-looking mushroom. A flat, creamy-brown cap to the mushroom soon begins to darken. As the mushroom ages, it seems to melt and begins to drip to the ground. This deliquescence gives the ink caps their name as they look like they are oozing ink. The common ink cap (aka Coprinopsis atramentaria) has a second creepy string to its bow. It is also known as tippler’s bane. The mushroom has a very mild flavor and is entirely edible despite its unappetizing appearance. The danger of the mushroom comes from mixing it with alcohol. The fungus produces a chemical called coprine which can be deadly if mixed with alcohol, even if alcohol is drunk days after the mushroom is eaten.

6 Octopus Stinkhorn

Clathrus archeri has two common names: octopus stinkhorn and Devil’s fingers. Whatever you call it, it certainly has a unique look. Like other stinkhorn fungi, it hatches from an egg-like growth just beneath or on the surface. This stinkhorn produces a foul-smelling substance to attract the flies needed to carry its spores to new locations. It sprouts 4–8 “fingers” when it hatches. Other stinkhorn fungi are edible. Although gelatinous fungal eggs may not seem like the most appealing foodstuffs, they are considered to be delicacies in some countries. The Devil’s fingers, however, are not known to be prized in any cuisine.

5 Cedar-Apple Rust

Cedar-apple rust is a fungus with a complex life cycle, none of it particularly pretty. The fungus lives on apples and juniper trees, but it cannot survive entirely on either of them. In May, the spores land on the leaves of apples. The leaves develop unsightly spots on their undersides. These shed spores into the air where they drift until they land on a juniper. Here, they drive the juniper to develop round, tumorlike galls. These are the “cedar apples” that give the fungus its name. From the galls, yellow spikes emerge. When the first warm rain hits these horns, spores are released to infect apple trees and continue the cycle.

4 Cordyceps

Cordyceps fungi are highly prized in many alternative medicines. In China, they are used in soups. Nothing so strange about that, mushroom soups are common the world over. The difference is that Cordyceps grow from the bodies of insects and arachnids. A single spore landing on an insect can be enough to infect it. The fungus grows rapidly within the body, using the insect’s internal organs for food. When the insect is used up, the fungus must break free to release its spores. It does this by sending long, spore-producing spikes through any available opening. Some Cordyceps are particularly cunning. Once inside the body of an ant, the fungus secretes chemicals that drive the ant to climb high into trees and cling on with their mandibles. From this high position, the fungus is able to more effectively spread spores to infect other ants.

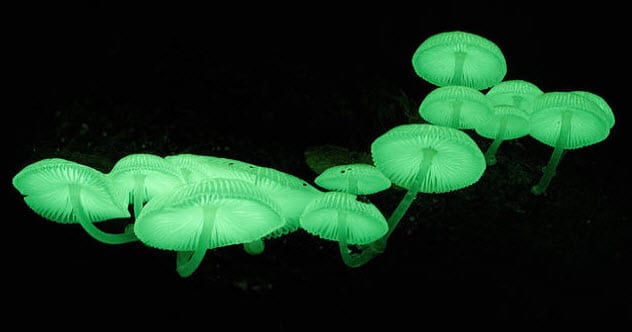

3 Luminous Mushrooms

Many fungi are bioluminescent and produce light, but no one is entirely certain just why they do it. The dominant idea is that the light is used to lure insects in much the same way that stinkhorns use their odor. Like bugs around a porch light, these insects hit the mushrooms and help to spread spores. The phenomenon of glowing fungi has been noted for millennia. The eerie green glow of rotting wood (actually produced by the fungi consuming it) has been called fox fire and faerie fire. The light is caused by an enzyme called luciferase. Now that we know how the fungi produce light, there have been suggestions that genetic engineering could be used to make trees that glow in the dark to light paths.

2 Brain Fungus

While Cordyceps fungi do target the brains of insects, those fungi look nothing like brains. But Gyromitra esculenta does. Morel mushrooms are highly prized by chefs and diners for their sublime taste. The edible species all share a honeycomb appearance. The world of mycology, though, is full of fungi that resemble edible ones but are best avoided. Many species related to the morel are given the name “false morel” because they can lead the unwary into consuming them. Gyromitra esculenta may look disgusting—and it is poisonous in its uncooked form—but it is actually eaten in Scandinavia. Even cooked, they have been linked to deaths. Repeated eating of Gyromitra esculenta can lead to toxic buildup in the body.

1 Anemone Stinkhorn

The anemone stinkhorn (aka Aseroe rubra) is yet another member of the stinkhorn family. It also has a link to the notoriously scary flora and fauna of Australia. The anemone stinkhorn was the first fungus native to Australia to be described. The scientific name refers to the sticky, reeking gleba common to the stinkhorns that is used to attract flies. Aseroe derives from the Greek meaning “disgusting juice.” The gelatinous, olive-brown gleba is full of spores. Immature specimens are covered in gleba, but it is slowly removed on the feet and bodies of the flies it attracts. After bursting out from its “egg,” the fungus produces 6–10 bifurcated arms or tentacles that give it a resemblance to an anemone.