But there are several skeletons in Apple’s closet: failed products and management gaffes, both with and without Steve Jobs. Let’s take a look at Apple’s top 10 failures.

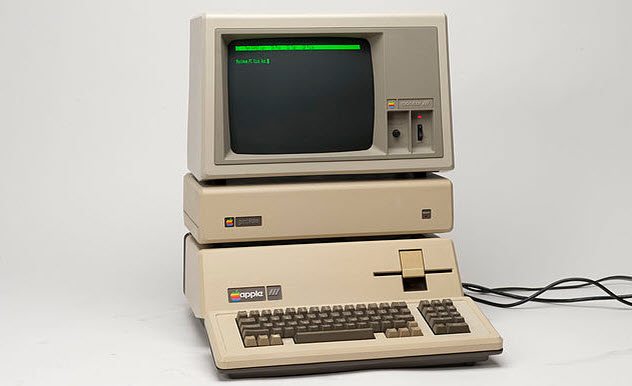

10 Apple III

At the end of every Apple press release, the company takes credit for ushering in the personal computer revolution with Apple II in the 1970s. Even their biggest competitors aren’t likely to argue the point. But by 1980, Apple knew it needed to break into the business market to maintain its early success—especially with longtime mainframe giant IBM working on its first personal computer. From these market concerns, the Apple III was born. With the goodwill associated with the Apple II name and several innovative features, including a fan-less design for quiet computing and an option for 512 KB of memory (unheard of for a personal computer at the time), the Apple III was expected to be a success. However, once the machine shipped in fall 1980, Apple was about to suffer its first major embarrassment. The Apple III was almost a nonstarter based on its price alone. Depending on configuration, the machine cost anywhere from $3,495 to $4,995—incredibly high prices for a personal computer in 1980 (or 2017, for that matter). The decision to not include a fan made the Apple III overheat, which caused chips to come loose and leave the machine nonfunctional. In a bizarre bit of tech support, Apple recommended that users lift the machine 5 centimeters (2 in) into the air and then drop it to reseat the chips.[1] With the extravagant price, nonfunctioning machines, and ridiculous tech “fix,” the Apple III died a quick death based on reputation alone. It was Apple’s first big failure, but it wouldn’t be the last.

9 The ‘Hockey Puck Mouse’

Apple is known for paying as much attention to their products’ design aesthetics as to the technology inside. When Steve Jobs introduced the first iMac in 1998, a new trend in computer design was launched. Beige boxes were out; colorful translucent plastics were in. This motif extended even to the iMac’s round mouse. Jobs declared it to be “the best mouse ever created,” but even before the iMac shipped, people were dubious. What came to be known as the “hockey puck mouse” was visually interesting but awful in everyday use. The tiny mouse and its unusual shape caused hand cramping, and its roundness meant that you couldn’t even tell if you were holding it in the right direction. (A later revision added a notch at the top of the mouse so that you could feel where the top was.)[2] Immediately, there was a market for two new products. One was a snap-on piece of plastic that gave the iMac’s mouse a more traditional shape. The other was a whole bunch of new mice that had conventional shapes but retained the translucent plastic aesthetic. As for Apple, they soon quit manufacturing the “hockey puck” and moved on to replacements like the Mighty Mouse and the Apple Magic Mouse.

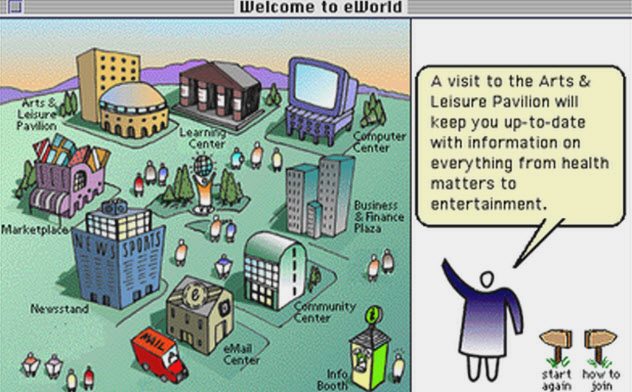

8 eWorld

When the Internet was first made available to the public, many newcomers to the “information superhighway” didn’t realize that all they needed was an Internet connection and a web browser to get online. This led to the rise in popularity of services like AOL, which not only provided dial-up Internet access but also applications that guided the user on how to access the many features of the ‘net. Apple made an ill-fated foray into AOL territory with eWorld, which provided a village metaphor for the Internet. High prices for dial-up service and eWorld’s availability for Macs only (at a time when 95 percent of computers ran Microsoft Windows) doomed eWorld from the start. Launched in June 1994, eWorld was dead by March 1996. Subscribers who launched the application after that were presented with a message that eWorld was no longer available.[3]

7 Mac Clones

Microsoft Windows gained dominance in the desktop computing market by running not only on IBM’s PCs but on the millions of IBM-compatible clones that started to pop up in the 1980s. Apple took a different strategy: If you wanted to run the Mac OS (OS stands for “operating system”), you had to buy a Mac. Beginning in the mid-1980s, several managers inside Apple pushed for the company to either make a version of the Mac OS for IBM-compatible PCs or follow IBM’s lead and allow Apple hardware to be cloned. These ideas were always quashed until 1994. At that point, Apple was in dire financial straits. In 1995, Apple tried the clone idea and granted Mac OS licenses to clone maker Power Computing. Several other companies, notably Motorola and UMAX, also signed up to license the Mac OS.[4] Unfortunately for Apple, they couldn’t replicate Microsoft’s success with this strategy. All the clone program did was cannibalize sales of Apple’s own Macs, with the company receiving only a small Mac OS license fee instead of the usual high profit margins on their hardware. Upon Steve Jobs’s return to Apple in 1997, he set out to find a way out of the clone deals that had been made in his absence. An easy out was found in the contracts, which only allowed the clone companies to ship versions of Mac OS 7. Jobs took an internal project that was to be Mac OS 7.7 and renamed it Mac OS 8. By 1997, the brief era of Mac clones was over. But the damage had been done, with Apple losing millions in hardware sales when it desperately needed them most.

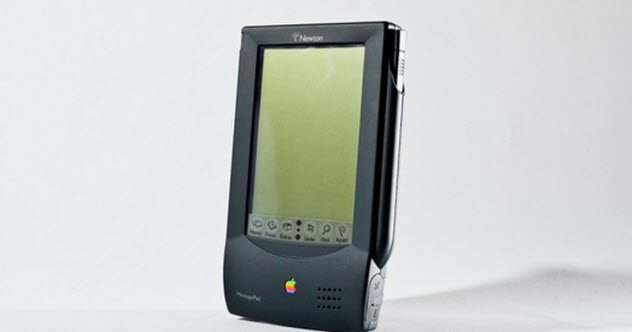

6 Newton

The pet project of former Apple CEO John Sculley, the Newton series of personal digital assistants (PDAs) is remembered as a major embarrassment for Apple. In many ways, the various Newton models were ahead of their time but suffered from one fatal flaw. Before the Palm Pilot PDAs of the late 1990s and early 2000s and the smartphones of today, the various Newtons were capable handheld computers. But the flagship Newton feature—handwriting recognition that would take text written with a stylus and turn it into computer text—was nowhere near ready for prime time.[5] The handwriting-to-text conversion mistakes by Newton were so bad that the feature was ridiculed in the Doonesbury cartoon strip, on Saturday Night Live, and in an episode of The Simpsons. As he did with the Mac clones, Steve Jobs quickly killed off the Newton line when he returned. With the iPhone and iPad, Apple has polished its reputation in the mobile device world.

5 PowerMac G4 Cube

Putting the PowerMac G4 Cube on a list of Apple failures is sure to rankle more than a few Apple fans. The beautifully designed desktop computer still has its devotees, some 18 years after its release. It’s even featured in the New York Museum of Modern Art.[6] But with the Cube, Apple overestimated how much their customers would pay for beauty. A base model retailed for $1,799 (without a monitor) at the same time that a more powerful and far more expandable PowerMac G4 tower was available for $200 less. Many who wanted a Cube waited until it hit the used market, where the Cube could be had for a price more in line with its technical specs. Introduced in July 2000, Apple realized that the Cube wasn’t selling and dropped it from its product line just a year later in July 2001.

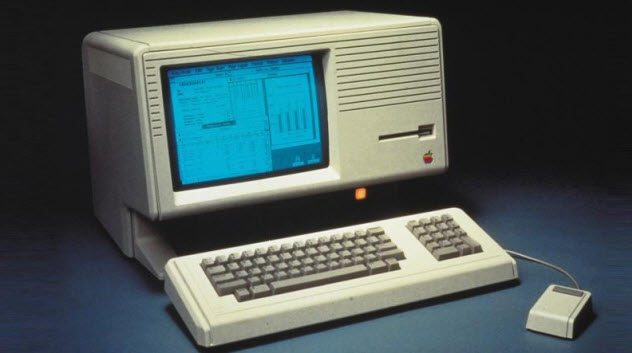

4 Lisa

The computers we all use today have a graphical user interface (GUI). This means that our screens have icons, which we click or tap. The documents and directories on our hard drives are represented by file and folder icons. But before the GUI revolution, computers were mostly text-based affairs. After you were presented with a command prompt, you typed in commands to run programs that were mostly made of text (and maybe some primitive graphics). Many believe that Apple’s first GUI-driven computer was the first Mac, released in January 1984. But Apple’s Lisa, with a similar GUI, was released a full year earlier in January 1983.[7] Although innovative for its time, the Lisa was crippled by two important factors. First, like the earlier Apple III, the Lisa was insanely expensive: $9,995 for a base model, or about $25,000 in 2018 money! Second, it was very slow, powered by a lowly 5 MHz Motorola 68000 processor. Those following the tech industry knew that Apple also had the Mac in the works and it was expected to be faster and cheaper. Sure enough, a year later, the Mac shipped with the same 68000 CPU but running at 8 MHz, a 60 percent speed boost over the Lisa. It didn’t take consumers long to figure out that the Mac was a better deal. Existing Lisas in inventory were converted to run Mac software and renamed the “Macintosh XL.” And those that still didn’t sell wound up in a landfill.

3 Pippin

Never heard of the Pippin? Many outside of Japan haven’t, either. This was Apple’s tentative foray into the gaming console market. But instead of making a dedicated console, they repurposed the insides of the Macintosh Classic II into something that looked like a gaming machine and included a game controller. It’s hard to say what Apple was trying to accomplish. Perhaps it was to encourage developers to write more games for the Mac. Or maybe it was to ease into the console market by using existing hardware rather than spending R&D money on a new platform. Either way, Apple was tentative with this initiative and first tested it in the Japanese market. Once the Pippin was crushed by the competitors of its time, like the Nintendo 64, Apple pulled support for the console. It was available for sale in the United States for a short while, starting in June 1996. But within a year, it was pulled from both Japanese and American shelves.[8]

2 Copland

After making waves with the Mac and its GUI in 1984, Apple was in something of a quandary. Users loved the Mac OS, which was innovative for 1984. But technology moved fast back then, just as it does today. Apple needed to keep up with modern standards but was afraid to mess too much with the beloved Mac OS. Instead, for a whopping 17 years, Apple kept hacking on to the Mac OS code base to try to keep up with modern computing needs. Finally, the company shipped the much more modern Mac OS X in 2001. Copland was an internal project to deliver a new OS that would have the modern features needed but retain backward compatibility with the original Mac OS. Among the newer features was true multiuser support and protected memory so that one crashed application couldn’t crash the whole computer. Apple started the project in 1994 but delivered only one preview release for software developers in 1996.[9] With untold millions of dollars spent on the project, Apple’s then-CEO Gil Amelio basically killed the project when he decided to buy an existing OS that could be retooled as the new Mac OS successor. Apple ended up buying Steve Jobs’s NeXT for its highly admired OpenStep OS (previously known as NeXTSTEP), bringing Jobs back to Apple after the 1985 boardroom coup that led to his departure. Copland may be known only to the true Mac faithful. However, given the money spent on it and Apple’s inability at the time to create its own modern OS, Copland ranks as one of the company’s biggest failures.

1 Lemmings Commercial

At the January 1984 product launch for the Mac, Apple showed the innovative commercial “1984,” which also aired during the Super Bowl that year. That commercial, directed by famed director Ridley Scott, is now legendary. Advertising Age put the commercial atop its list of the greatest ads of all time. For a follow-up, Apple and its advertising firm, Chiat/Day, bought ad time for the 1985 Super Bowl. Ridley Scott wasn’t available this time around, so his brother, Tony, directed the new commercial, “Lemmings,” instead. The ad was to promote the concept of the “Macintosh Office,” which was not a product per se but a bundle of technologies that would allow a group of Macs to be networked to easily share files and printers. “Lemmings” showed a group of businessmen, dressed in suits and carrying briefcases, blindly following each other and walking off a cliff. Based on the voice-over’s promise of the Macintosh Office, the last person stops. Whereas “1984” had been dark but inspirational, “Lemmings” was seen as insulting to the customers it was trying to draw in.[10] After creating the “greatest commercial of all time,” the new ad signaled the beginning of a dark period for Apple. By the end of the year, Steve Jobs was gone and Microsoft had begun their march toward dominance with Windows on every IBM-compatible PC. Despite small victories here and there, Apple didn’t fully recover until Jobs unveiled the iMac in 1998. Leaman Crews is an IT professional and former newspaper publisher and editor who shares stories about technology, music, and pop culture.