This list uncovers ten artifacts of history found by locals and civilians. And begs the question—what better reason to do a more thorough search through your attic or basement?

10 Ancient Greek Crown—Hellenistic Age

Life became a little brighter for a man from Somerset, England, who has since chosen to remain anonymous. The fortunate gentleman inherited a great many possessions from his grandfather, a collector who followed his passion around the world. One of the inherited assets was a cardboard box, stored under the man’s bed. It was forgotten for a decade or longer until, at last, the rough, likely dust-covered box again saw the light of day. Under faded newspaper, the man from Somerset discovered a crown of gold. Unsure of what had been found, he decided to call in the experts. An appraiser from Duke’s of Dorchester in Dorset, Guy Schwinge, arrived at the cottage. To say he was astonished by the laurel wreath of gold might be an underestimation. The artifact weighed under half a kilogram (1 pound) and was only 20 centimeters (8 inches) across. Schwinge estimated the wreath to be Ancient Greek in origin, perhaps 2300 years old, probably from the Hellenistic Age. The Hellenistic Age was ushered in by the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and ended with the rise of Augustus in Rome in 31 BC. The exquisite golden laurels of Ancient Greece were granted as prizes for athletes and artists, worn ceremonially, and often left with aristocratic family members after their passing. After further appraisal, the pure gold crown was estimated to be worth upward of $130,000. The auction by Duke’s of Dorchester was set for June 9, 2016, where it was anticipated the piece would fetch as much as $200,000.[1] All from a box left under a bed.

9 Lost Caravaggio Painting

In 2014, a family in Toulouse, France, ascended to their attic to address a water leak. Behind an old mattress against a wall, they discovered a dust-covered, partially water-stained painting. The family, who asked for anonymity, called an auctioneer for an appraisal. Marc Labarbe, the auctioneer, studied the 1.4-meter by 1.8-meter (5-foot by 6-foot) painting and deemed it worthy of further inspection. He took a picture of the painting and sent it to Paris to an appraiser of art, Eric Turquin. It took five years before Turquin was able to see the painting for himself. Well worth the wait. The painstakingly cleaned canvas had been painted in 1607—Caravaggio’s >em>Judith and Holofernes. In a story from the Old Testament, Judith of Bethulia slipped into the tent of a drunken, or sleeping, Assyrian general, then beheaded him. The painting depicts Judith’s last stroke of decapitation. A Caravaggio, indeed, Turquin agreed—one that had been lost to the world for 400 years. He authenticated the painting, worth up to $170 million. Doubt surrounded the painting’s authenticity, as a more modest version of the painting was already displayed in the National Gallery of Ancient Art in Rome. However, X-rays and testing revealed brush strokes that were changed before the artwork was completed. Forgeries lack those alterations. Authenticated and restored, the masterwork was set to be sold at auction. A private buyer bought the painting before the auction, for a price that was also kept private.[2]

8 Diamond Ring

A woman from Isleworth, West London, attended a car boot sale, or yard sale, where she perused a display of fake jewelry. She bought a large “diamond” ring in 1987 for £10 ($13). It was clouded and rather unremarkable in appearance. She wore it for over two decades before a jeweler inspected the ring more closely. They advised her to have it appraised. The large diamond was real—a 26-carat diamond from the 19th century. Sotheby’s in London authenticated the jewel, which then sold for an incredible £656,750 ($850,000).[3]

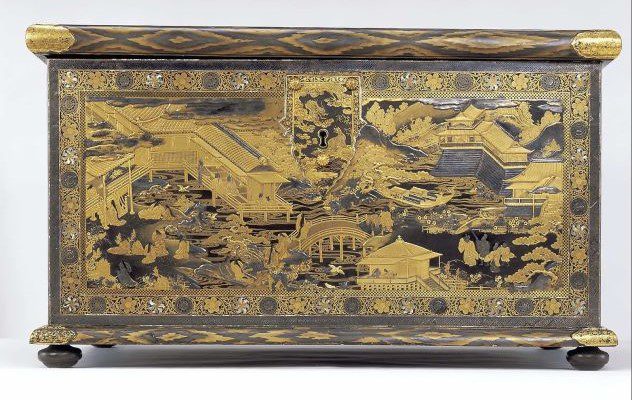

7 Gold Lacquer Chest

In 1970, a French shell engineer browsing lacquerware bought a 1.5-meter-long (5-foot) chest for £100 ($130), which today would be about £1300 ($1600. He resided in South Kensington for sixteen years, using the chest to prop up his television. When he retired and was able to return home to the Loire Valley, the chest became a bar. And there it sat until his passing when the house was emptied, and its contents were appraised. To the appraisers’ amazement, the television stand turned bar storage was a treasure missing since the 1940s. The Victoria and Albert Museum had searched for the chest through collectors and auction houses, a search that spanned half a century. Strangely enough, the artifact was less than a mile away from the museum. The cedar and gold lacquer chest was crafted in the 1600s, a masterpiece by a master crafter, Kaomi Nagashige of Kyoto/Kyote, Japan. It remained with the Dutch East India’s Japanese office until it was sold in 1658. The buyer was a Minister of France, Cardinal Mazarin, who left the chest to his family for generations. From France, the chest traveled to England, where it was bought by the English novelist William Beckford. In 1882, the chest was sold to Sir Trevor Lawrence, a surgeon and art collector who died in 1913. It resided with a Welsh coal mine owner, Sir Clifford Cory, until 1941 when the chest was lost to history. Except, Zaniewski, a Polish doctor living in London, had bought. Zaniewski sold it to the French shell engineer in 1970, who kept it until after 1986. Only then was it seen by brothers and auctioneers Phillippe and Aymeric Rouillac. Nagashige’s masterwork was auctioned on July 9, 2013. It was bought by the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam for £6.3 million ($7.75 million).[4]

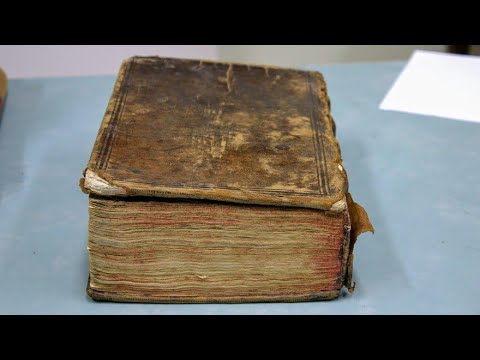

6 Shakespeare’s Last Play?

John Stone, a scholar of the University of Barcelona, was browsing the Royal Scots College’s library, Salamanca, when he noticed a book of English plays. Within the pages of plays, he found William Shakespeare’s The Two Noble Kinsmen. Published in 1634, written from 1613 to 1614 with playwright John Fletcher, the play was completed before Shakespeare returned to his home in Stratford-Upon-Avon. It was possibly the last play Shakespeare wrote before he died in 1616. The Two Noble Kinsmen remains one of the lesser-known works of Shakespeare. The edition was bound in leather, the original binding from the 1600s. Shakespeare may have written Acts I and V, though that is still debated by scholars. While the book has not been sold, to give an estimation of worth, Shakespeare’s First Folio was sold by Christie’s auctioneers in 2020 in New York for more than £7.33 million ($9 million).[5]

5 Painting in a Kitchen, Cimabue

Cimabue, or Cenni di Pepo, was an artist of the Italian Renaissance. He was born in Florence and was a painter in the 14th century. Cimabue didn’t sign his eleven pieces of artwork painted on wood; only those eleven are accredited to him. One of them was found in France, hanging in a house in Compiègne. The woodwork painting was only 26cm x 20cm (10″ x 8″), but it was a masterwork even so—known as Christ Mocked. The house’s owner, a woman who remains anonymous, then 90 years old, considered it mere religious kitsch. In other words, worthless. It had been in the kitchen for decades; no one in the family knew where the painting had been acquired. In 2019, the owner of the house decided to sell and move. They called auctioneers from the auction house Acteon in Senlis, France. Philomène Wolf arrived at the house. With only a week to appraise the contents of the house, Wolf saved the “worthless” work from the trash bin. It was sent to be further appraised at the Cabinet Turquin in Paris. Turquin’s determined the art piece to be a Cimabue. In fact, the small painting was from 1280, part of a diptych, or a set of painted wooden panels, that portrayed eight scenes of the “passion and crucifixion of Christ.” Philomène Wolf estimated the painting to sell for about $400,000. Turquin’s expected an auction offer of nearly $7 million. To everyone’s utter stupefaction and glee, the painting sold for nearly $27 million.[6]

4 Chess Piece in a Drawer

A walrus-ivory chess piece, nicked, faded, and worn, was found in a Scottish family’s kitchen drawer. Their grandfather, an antique dealer, had purchased it for £5 ($6) in 1964 in Edinburgh. As stated by the family, neither their grandfather nor any other member of their family knew it was of any value. After finding the chess piece, the grandchildren brought it to Sotheby’s in London. Watch this video on YouTube Researchers at Sotheby’s knew the rook was world-famous. It was one of 93 chess pieces from the famous Lewis Chessmen. Five of those Viking artifacts, 900 years old, are still missing. They were originally found on the Isle of Lewis, Outer Hebrides, Scotland. The rook had been lost for nearly two hundred years. The auction house estimated the piece to be worth £1 million ($1.3 million).[7]

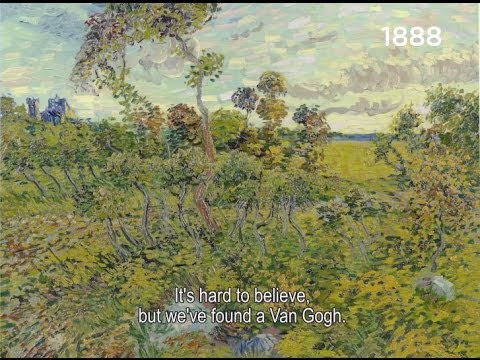

3 (Another) Painting in an Attic, Van Gogh

In 1910, a Norwegian industrialist, Christian Mustad, bought Sunset at Montmajour, which he believed to be painted by the Dutch Post-Impressionist painter Van Gogh. A French ambassador to Sweden convinced Mustad that the painting was a forgery. It was banished to the attic of Mustad’s Norwegian house, where it remained until 1991. The inheritors of the house brought it to the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. They were told the painting was a forgery, mainly because it was unsigned. Van Gogh signed his paintings with his first name, Vincent, and sometimes hid the signature within the painting. In 2011, the painting was reassessed by the Van Gogh museum. Though it took two years, Sunset at Montmajour was finally accredited to the master painter. It had been completed near Van Goh’s house in Arles, France, on July 4, 1888, only two years before the artist’s death. A letter from Van Gogh to his brother, Theo, revealed that the painting hadn’t been signed because of the artist’s disappointment with the piece. “It was well below what I’d wished to do,” Vincent wrote, which led to the painting’s authentication. The Van Gogh Museum chemically analyzed the paints from the Sunset painting. The pigmentation of the paints was the same as those used by the artist. Scans of the canvas were matched to other paintings of Van Gogh’s from that month—Van Gogh painted 2,100 pieces in his lifetime. He wrote about many of them to his brother, who had been responsible for selling the artwork. The artist only sold one painting in his lifetime, the Red Vinyard, for 400 Belgian francs, $400. An anonymous owner bought, Sunset at Montmajour. Its sale price is unknown, though in 1987, the famous Vase With Fifteen Sunflowers sold for nearly $33 million. The most famous Van Gogh, Starry Night, is worth hundreds of millions.[8]

2 The Garden Planter

It was 1982 when a Northumberland family bought a house near Hadrian’s Wall, Newcastle, England. Their dilemma: what to do with the 2.1-meter (6′ 9″) “trough” in their backyard? They decided to use it for planting… for thirty years—until they saw a similar structure for sale at an auction house. Upon inspection of the garden planter, a copper plate on the back read, “Bought from Rome in 1902.” Carved into the front were the Three Graces from Greek mythology: charm, beauty, and creativity. Experts were called for an appraisal, including Guy Schwinge, of Duke’s auction house in Dorset, England. The family was told their planter was a 2,000-year-old sarcophagus of Carrara marble from the 1st or 2nd century AD. It may have been taken from a mausoleum, the resting place of an affluent Roman. The sarcophagus was lifted from the property and brought to Dorchester, where it was auctioned. While the auction price is unknown, a similar sarcophagus sold for over $130,000.[9]

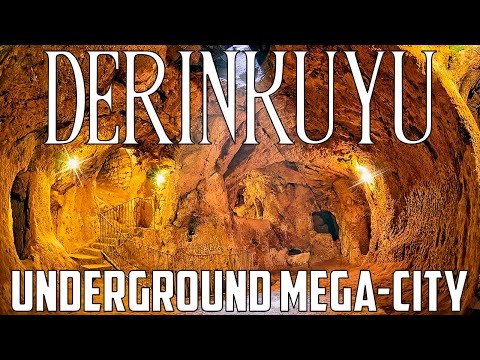

1 The Ancient City in a Basement

A man in Turkey was in the middle of renovating his basement when he knocked down a wall to reveal the discovery of a lifetime. It was 1963 in Cappadocia when the basement wall came down and uncovered a room that led to a tunnel. Where did the tunnel lead? Almost 61 meters (200 feet) underground—to an entire ancient Byzantine-era city of stone. Scholars debate the date, ranging from 2000 BC for the Hittites, 700 BC for the Phrygians, or AD 780–1180 for the Christians. It may have been in use up to the 1920s as a refuge from natural disasters and war. The city was called Derinkuyu: 18 levels of inhabitable space, all of which could be individually blocked off with rolling stone doors. Deinkuyu connected to other underground cities through tunnels that spanned miles and had more than six hundred entrances. Twenty thousand people, or more, would have thrived, with food storage rooms, including those for livestock, stables, schools, kitchens, chapels, wineries, and wells. Also, tombs and a dungeon were found. Derinkuyu became a tourist attraction in 1969, open to the public.[10]