The lister has set out to examine both sides of the debate over the ethics and legality of capital punishment, especially in the US, and chooses neither side in any of the following entries. They are not presented in any meaningful order.

What is the purpose of punishment? We take our lead from one major source, our parents—and they no doubt took their lead from their own parents. When your young child emulates what he just saw in a Rambo movie, you give him a stern lecture about what is real and what is not, what is acceptable in real life and what is not. When your child tries some crazy acrobatic move off a piece of furniture and hurts himself, you might spank him to be sure that he remembers never to do it again. So when the child grows up, breaks into a home, and steals electronics, he gets caught and goes to prison. His time in prison is meant to deprive him of the freedom to go where he wants anywhere in the world, and to do what he wants when he wants. This is the punishment, and most people do learn from it. In general, no one wants to go back. But if that child grows up and murders someone for their wallet or just for fun, and they are in turn put to death, they are taught precisely nothing, because they are no longer alive to learn from it. We cannot rehabilitate a person by killing him or her.

Nevertheless, if would-be criminals know undoubtedly that they will be put to death should they murder with premeditation, very many of them are much less inclined to commit murder. Whether or not would-be criminals are wary of committing the worst crime is an important—and probably impossible—question to answer. Murder still happens very frequently. So some criminals disregard this warning for various reasons. But the fact does remain that many criminals who ride the fence on committing murder ultimately decide to spare the victim’s life. In a larger sense, capital punishment is the ultimate warning against all crimes. If the criminal knows that the justice system will not stop at putting him to death, then the system appears more draconian to him. Hence, he is less inclined to break and enter. He may have no intention of killing anyone in the process of robbing them, but is much more apprehensive about the possibility if he knows he will be executed. Thus, there is a better chance that he will not break and enter in the first place.

If the foreknowledge of any punishment is meant to dissuade the criminal from committing the crime, why do people still murder others? The US had a 2012 murder rate of 4.8 victims per 100,000—meaning that nearly 15,000 people were victims of homicide that year. Capital punishment does not appear to be doing its job; it doesn’t seem to be changing every criminal’s mind about killing innocent people. If it does not dissuade, then it serves no purpose. The warning of life in prison without parole must equally dissuade criminals.

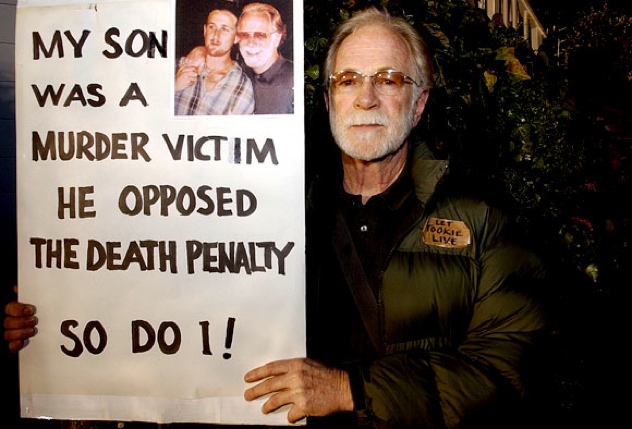

There are many victims of a single murder. The criminal gets caught, tried, and convicted, and it is understood that the punishment will be severe. But the person he has killed no longer has a part to play in this. Unfortunately, the murderer has deprived his family and friends of a loved one. Their grief begins with the murder. It may not end with the murderer’s execution, but the execution does engender a feeling of relief at no longer having to think about the ordeal—a feeling which often fails to arise while the murderer still lives on. A system in place for the purpose of granting justice cannot do so for the surviving victims, unless the murderer himself is put to death.

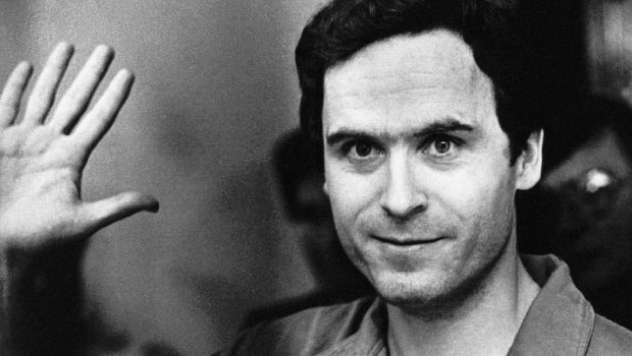

It is strange that a nation would denounce the practice of murder by committing the very same act. By doing so, we’re essentially championing the right to life by taking it from others. True—as a whole, we are not murderers, and understandably refuse to be placed in the same category as someone like Ted Bundy. But to many opponents of the death penalty, even Ted Bundy should have been given life without parole. The fact that he murdered at least thirty people—for the mere reason that he enjoyed doing it—has no bearing on the hypocrisy, the flagrant dishonesty, of the declaration that such a person deserves to be killed because he had no right to kill. If the goal of any punishment, as stated above, is to teach us those things we should not do, then the justice system should more adequately teach the criminality of killing by refusing to partake in it.

If you read about Bundy’s life in prison, waiting nine years for his execution, you will see that the man exhausted every single legal point he and his lawyers could think of, all in an attempt to spare him execution. He “defended” himself in prison interviews by blaming pornography for causing his uncontrollable teenage libido, and for causing him to think of women as objects and not humans. He attempted to have his death sentence commuted to life without parole by explaining that it was all pornography’s fault, and that had it never existed, he would have been a good person. When that didn’t work, he pretended to come clean and tell police where the bodies of unfound victims were, so that their families could have closure. He never once admitted that he was a bad person, and just before his execution, he claimed that he hadn’t done anything wrong. It was obvious that he feared being put to death. He did his best to avert it. This means that he did not fear life in prison—at least not as much as he feared capital punishment. He had many opportunities to kill himself in his cell, but he did not. He might have done it a month before his execution, when all hope for clemency was gone—but he was afraid of death. How many would-be murderers have turned away at the last second purely out of fear of the executioner’s needle?

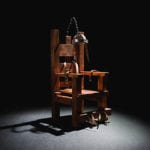

In the end, though, death is always at least a little painful. Perhaps the only truly peaceful way to go is while asleep—but no one has ever come back to say that this didn’t hurt. If your heart stops while you sleep, it is certainly possible that your brain will recognize a problem and wake you up at the very moment when it is too late. So what we cannot help but let Nature do, we ought not to force on others for any reason. If we do so, it might be fair to say that we law-abiding people, who embody the justice system, are guilty of equal cruelty towards criminals who commit murder. The United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights, for one, dictates that “no one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.” In the US, there are five legal methods of execution: lethal injection, electrocution, firing squad, hanging, and gassing. These are all intended to be as painless as possible, but they all run the risk of accidents. John Wayne Gacy, who was not afraid of death, was executed via lethal injection—the most efficient, risk-free method. Yet his death did not go as planned. The sodium thiopental entered his bloodstream successfully and put him to sleep. The pancuronium bromide was then administered successfully to paralyze his diaphragm. This would cause asphyxiation if the next chemical, potassium chloride, were not immediately administered to stop the heart. But the potassium chloride had congealed in its tube before Gacy was brought into the room. He was unconscious and unable to breathe for several minutes while the last drug’s tube was changed. His death took eighteen minutes, instead of the usual seven. And whether or not he was in great pain is impossible to determine.

It’s true that cruelty should not be legally tolerated—and the five methods listed above are very efficient in killing the condemned before he or she is able to feel it. Granted, we are not able to ask the dead whether or not they felt their necks snap, or the chemicals burn inside them—but modern American executions very rarely go awry. It does happen, but the reported accidents since 1976 number about ten nationwide, out of 1,328. When the condemned is fastened into the electric chair, one of the conductors is strapped securely around the head with the bare metal flush against the shaved and wet scalp. This permits the electricity to be conducted directly into the brain, shutting it off more quickly than the brain can register pain. Hanging causes death by snapping the neck of the condemned around the second vertebrae—instantly shutting off the brain’s ability to communicate with the rest of the body, and causing the heart to stop within seconds. The firing squad involves five men shooting the heart of the condemned with high-powered rifles. The heart is completely destroyed and unconsciousness follows within seconds. The gas chamber is now no longer forced on the condemned, because it frequently appeared to cause more pain than was expected or acceptable. The gas is usually hydrogen cyanide, which inhibits mitochondrial respiration in every cell of the entire body, theoretically shutting off the brain like a light switch. But it requires that the condemned breathe deeply.

Consider a pedophile who kills an infant girl by raping her. There is an unwritten “code of honor” in prisons that virtually requires inmates to kill such offenders. Probably half of America’s prisoners were in some way abused as children, and harbor a seething hatred for those who abuse children. The murdering pedophile is given the death penalty, but will probably spend ten years beforehand in prison. He will most likely be housed in solitary confinement for his own protection, but there are frequently holes in such protection, and the inmates may find their way to him. And if this happens, pedophiles are often gang-raped, castrated, beaten to death, stabbed, and sometimes even beheaded before guards—who may deliberately ignore the scene—can save them. Most prisoners consider each other to be in the same predicament, and treat each other quite well in general. But they are still in prison, and despair about their lack of freedom. What is life like for Zacarias Moussaoui, the member of the September 11 hijacking teams who got caught a month before the attack? A single juror saved him from death. He has, since 2006, been incarcerated for twenty-three hours per day in a tiny concrete cell, with one hour of daily exercise in an empty concrete swimming pool; he has no access to other inmates, and only rare contact with guards, who say nothing to him; he can see nothing of the outside world except a tiny sliver of sky—and his will be his life. Capital punishment is an unnecessary threat.

The justice system basically attempts to mete out punishment that fits the crime. Severe crimes result in imprisonment. ”Petty larceny” is not treated with the severity that is meted to “grand theft auto,” and the latter, consequently, receives more time in prison. So if severe—but non-lethal—violence toward another is found deserving of life without parole, then why should premeditated homicide be given the very same punishment? This fact might induce a would-be criminal to go ahead and kill the victim he has already mugged and crippled. Why would it matter, after all? His sentence could not get any worse. If murder is the willful deprivation of a victim’s right to life, then the justice system’s willful deprivation of the criminal’s right to the same is—even if overly severe—a punishment which fits the most severe crime that can be committed. Without capital punishment, it could be argued that the justice system makes no provision in response to the crime of murder, and thus provides no justice for the victim. FlameHorse is an absolute pacifist who loves animals, but eats burgers. He will never write a list about Ted Nugent.