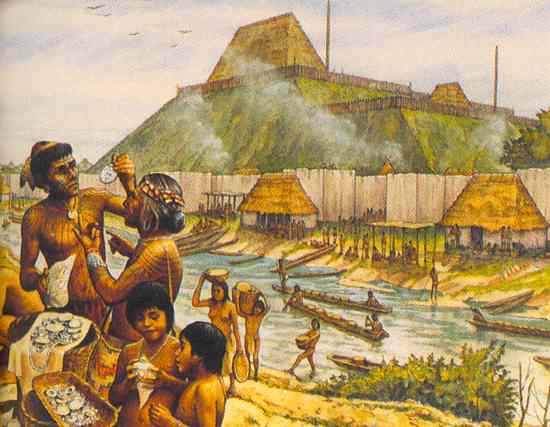

Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site is an ancient indigenous city (c. 600–1400 AD) near Collinsville, Illinois. It is the largest archaeological site related to the Mississippian culture, which developed advanced societies in central and eastern North America, beginning more than five centuries before the arrival of Europeans. It is a National Historic Landmark and designated site for state protection. In addition, it is one of only twenty World Heritage Sites in the territory of the United States. It is the largest prehistoric earthen construction in the Americas north of Mexico. It is also home to a wooden structure that appears identical in function to Stonehenge. Cahokia was the largest urban center north of the great Mesoamerican cities in Mexico at the high point of its development. Although it was home to only about 1,000 people before 1050, its population grew explosively after that date. Archaeologists estimate the city’s population between 8,000 and 40,000 at its peak, with more people living in outlying farming villages that supplied the main urban center. In 1250, its population was larger than that of London, England. If the highest population estimates are correct, Cahokia was larger than any subsequent city in the United States until about 1800, when Philadelphia’s population grew beyond 40,000.

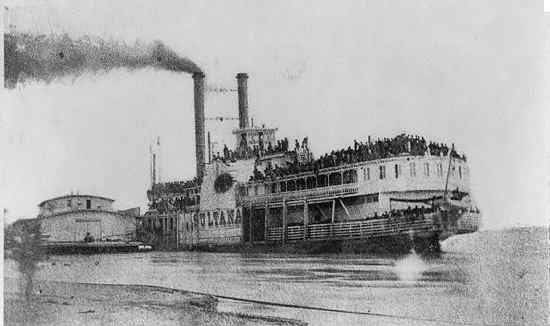

The steamboat Sultana was a Mississippi River paddle wheeler, destroyed in an explosion on 27 April, 1865. This resulted in the greatest maritime disaster in United States history. An estimated 1,800 of the 2,400 passengers were killed when one of the ship’s four boilers exploded, and the Sultana sank not far from Memphis, Tennessee. This disaster was mostly forgotten by history because it took place soon after the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln and during the closing weeks of the Civil War. Most of the new passengers were Union soldiers, chiefly from Ohio and just released from Confederate prison camps such as Cahawba and Andersonville. The U.S. government had contracted with the Sultana to transport these former prisoners of war back to their homes. The cause of the explosion was a leaky and poorly repaired steam boiler. The boiler (or “boilers”) gave way when the steamer was about seven to nine miles north of Memphis at 2:00 am in a terrific explosion that sent some passengers on deck into the water and destroyed a good portion of the ship. Hot coals scattered by the explosion soon turned the remaining superstructure into an inferno, the glare of which could be seen in Memphis.

Ziryab (789-857 AD) was a Persian polymath: a poet, musician, singer, cosmetologist, fashion designer, celebrity, trendsetter, strategist, astronomer, botanist, geographer, and former slave. Most people have never heard of Ziryab. Yet, at least two of his innovations remain to this day: he introduced the idea of a three-course meal (soup, main course, pudding), and he introduced the use of crystal for drinking glasses (previously metal was the primary material). He introduced asparagus and other vegetables into society and made significant changes and additions to the music world. He had numerous children, all of whom became musicians, and spread his legacy throughout Europe. He could perhaps be considered an ancient Bach. The list of societal changes Ziryab made is immense—he popularized short hair and shaving for men and wore different clothes based on the seasons. He created a pleasant-tasting toothpaste that helped personal hygiene (and longevity) and invented an underarm deodorant. He also promoted bathing twice daily.

Most people reading this will be familiar with the Great Chicago Fire that killed hundreds and destroyed 4 square miles of Chicago, Illinois. However, most people don’t know that a far worse fire occurred in Peshtigo, Wisconsin, on the very same day. The October 8, 1871, Peshtigo Fire in Peshtigo, Wisconsin, was the conflagration that caused the most deaths by fire in United States history. On the same day as the Peshtigo and Chicago fires, the cities of Holland and Manistee, Michigan, across Lake Michigan, also burned, and the same fate befell Port Huron at the southern end of Lake Huron. By the time it was over, 1,875 square miles of forest had been consumed, and twelve communities were destroyed. Between 1,200 and 2,500 people are thought to have lost their lives. The fire was so intense it jumped several miles over the waters of Green Bay and burned parts of the Door Peninsula, as well as jumping the Peshtigo River itself to burn on both sides of the inlet town. Surviving witnesses reported that the firestorm generated a tornado that threw rail cars and houses into the air. Many of the survivors of the firestorm escaped the flames by immersing themselves in the Peshtigo River, wells, or other nearby bodies of water. Some drowned while others succumbed to hypothermia in the frigid river.

Gil Eannes is hardly a household name, nor is that of the place associated with the Portuguese explorer, Cape Bojador. Nor indeed did Eannes discover the cape: the place had been known for many years. To journeyers of Eannes’s time, Bojador represented an unbreachable barrier, a point of no return, and it was the achievement of this reluctant hero to pass that invisible boundary in 1434. In doing so, he opened new territory, not only on land but in the mind, and thus made possible the golden age of Portuguese exploration, with all its glories and horrors. At that time, conventional wisdom maintained that the Sun was boiling hot at the Equator. Thus, even if a ship could get past Cape Bojador, the equatorial Sun would eventually burn it to powder. Furthermore, should a vessel somehow make it past all other hazards, its crew would most surely meet unspeakable monsters in the sub-equatorial region known as the Antipodes. By having the courage to risk his life (consequently opening up new worlds), Eanes was effectively behind the European age of discoveries to come. He was, however, also in part to blame for what would become a thriving trade in slaves for centuries after.

Joseph Warren (1741–1775 AD) was regarded by many in his time as the true architect of the American Revolution. He was the key figure in one of history’s most famous tea parties. He wrote a set of Resolves that served as the blueprint for the first autonomous American government. He delivered a speech that sparked the first battles of the Revolutionary War. He sent Paul Revere out on one of history’s most famous rides (see below). Before the Declaration of Independence, he was the only Patriot leader to risk his life against the British on the Battlefield (Sandler 55). And, remarkably, he has been largely lost to history. He was surrounded by names we are all familiar with, and yet his own name is barely ever heard these days. Interestingly, his brother went on to found Harvard Medical School, and 14 U.S. States have a Warren County named after him.

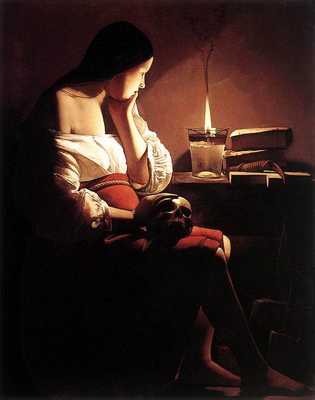

Georges de La Tour (March 13, 1593, Vic-sur-Seille, Moselle — January 30, 1652, Lunéville) was a painter who spent most of his working life in the Duchy of Lorraine (which was absorbed into France between 1641 and 1648) during his lifetime. He painted mostly religious scenes lit by candlelight. After centuries of posthumous obscurity, during the 20th century, he became one of the most highly regarded French 17th-century Baroque artists. He was known as the Painter to the King (of France) and was regarded as one of the greatest artists in his lifetime. Very little of his work survives, and the reason for his obscurity is unknown, but thanks to the efforts of Hermann Voss, a German scholar, in 1915, his work was rediscovered.

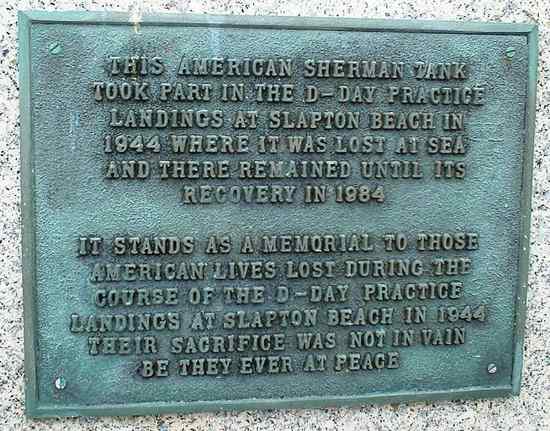

Exercise Tiger, or Operation Tiger, were the code names for a full-scale rehearsal in 1944 for the D-Day invasion of Normandy. During the exercise, an Allied convoy was attacked, resulting in the deaths of 749 American servicemen. The lack of widespread knowledge of this exercise was due to intentional efforts (unlike most others on this list). As a result of official embarrassment and concerns over possible leaks just before the real invasion, all survivors were sworn to secrecy by their superiors. Ten missing officers involved in the exercise had Bigot–level clearance for D-Day, meaning that they knew the invasion plans and could have compromised the invasion should they have been captured alive. As a result, the invasion was nearly called off until the bodies of all ten victims were found. With little or no support from the American or British armed forces for any venture to recover remains or dedicate a memorial to the incident, Devon resident and civilian Ken Small took on the task of seeking to commemorate the event after discovering evidence of the aftermath washed up on the shore while beachcombing in the early 1970s.

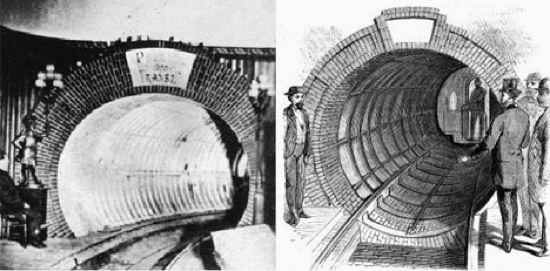

In 1904, New York’s modern subway system was officially opened—changing the city forever. But what most people don’t know is that it was not the first subway. Because of terrible congestion on Broadway, Alfred Ely Beach (the young owner of the fledgling magazine Scientific American) conceived of an idea—to build an underground railway, which used a giant fan to propel and suck a railcar back and forth through a tunnel. Because of the corruption of the commissioner of public works, William Tweed, Beach had to get consent to build his tunnel by pretending it was to be a mail delivery system. Tweed (whose income was derived largely from city transportation) did not veto the request. Beach and a small group of men began digging a tunnel under Broadway in the dark of night. The entire enterprise was kept secret, as dirt was hidden in the basement of a building Beach bought for that purpose. The work went well, but just before they could complete their first line, the press got wind of it, and it became public. Beach’s team worked extra hard to finish the subway, and in grand style, they opened to the public on March 1, 1870. He charged twenty-five cents per passenger to travel from Warren Street to Murray Street. It was a huge success—carrying over 400,000 passengers in its first year of operation. Unfortunately, Tweed was outraged and vetoed future extensions to the subway. Tweed was eventually imprisoned for his corruption, and permission was given for Beach to resume work extending the subway, but unfortunately, his private investors were fast disappearing due to the beginnings of an economic crisis. The subway was not completed and remained hidden under the city, completely sealed up (complete with the luxury car and machinery) until it was subsumed into the present City Hall Station.

Paul Revere famously rode through a darkened night to warn the American colonists that the British were coming, and this began the fight for liberty known as the American Revolution. Many of us know the poem telling of Revere’s famous ride. Remember, “Listen, my children, and you shall hear. Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere.” Many do not know that five riders also rode out to warn of the British coming. So, atop this list, we look at history’s forgotten riders. William Dawes was a Boston native and was told to ride to Lexington to tell Samuel Adams and John Hancock that they were wanted for arrest. Dawes was also tasked with telling the minutemen, soldiers who served the colonies, that the British troops were closing in. He was about 30 minutes behind Revere and had to walk back to Lexington after his horse threw him and ran away. Revere himself asked Sam Prescott to ride out on the night of April 18th. Sam knew the terrain well and was to act as a guide to Concord. When everyone had to split up to avoid British troops, Prescott alone carried the news to Concord that the British were coming. Prescott’s brother Abel rode out to warn some nearby small towns of the danger, and several riders were sent out in the area; however, their names weren’t recorded. Israel Bissell rode the longest that night because he actually started riding days before on April 13th. He rode for four days on the Old Post Road, almost 350 miles, shouting “to arms, to arms, the war has begun.” He did not cry, “the British are coming,” and neither did Revere. Revere was as quiet as possible on his much shorter midnight ride to make good time and evade the British troops. Because Bissell has been so forgotten by history, today’s historians question whether he even existed at all. Of all the riders, Sybil Ludington was the most in danger. She was 16, a girl, and the daughter of a Colonel when she set out on her ride on April 26th. Sybil rode for 40 miles, twice as long as Paul Revere, to warn Danbury, Connecticut, that the British were coming for them. Her father dispatched her to carry the message in the middle of the night. She used a stick to knock on doors and fend off highwaymen. She returned home just before dawn, uncaptured and unharmed. George Washington later commended her for heroism. A statue of her stands in Carmel, New York, in tribute to her challenging ride. Works Cited Sandler, Martin. Lost to Time. New York: Sterling Publishing Co, 2010. 55. Print Read More: Facebook Instagram Email