10 Child Labor

In Cambodia, the legal working age is 15 years old, but without diligent enforcement of this law, many clothing factories employ girls as young as 12. These children drop out of school to get a job because their families live in poverty. Abandoning their education, the girls become part of a system that forces them into a cycle that is impossible to escape. Regardless of the worker’s age, the average pay equates to roughly 50 cents per day. According to UNICEF and the International Labor Organization, an estimated 170 million children are currently working in the clothing industry all over the world. Workers are also forced to work overtime without increased pay, which means that mothers are forced to either leave their children alone or bring them to the factory. Many factories have a “day care,” which in reality is just a section set aside for the children to simply exist. There is no stimulation and no teachers or staff to take care of them. In its own way, bringing children to the factories may lead to child labor as well. Without any other stimulation, helping their mothers work may be one of the only ways for the children to fight off boredom.

9 Not-So-Fake Fur

With the general public becoming more aware of cruelty to animals, clothing retailers are seeing a growing demand for faux fur. Animal rights advocates would be horrified to find out that many products advertised as containing fake fur actually contain real fur. In many cases, it is cheaper for clothing manufactures to use less expensive animal hides, like rabbit or raccoon, than it would be to manufacture synthetic fur. The New York Times reported on a scandal in 2013, in which Neiman Marcus stores in the United States was selling multiple items labeled “faux fur” that were actually real. This is was not an isolated incident. The Federal Trade Commission includes fur on their website as one of the major issues found with retailers and explains to consumers how they can identify real versus fake fur. The Fur Act was originally created in the 1950s to protect buyers from purchasing furs labeled as “mink” that were actually much less valuable rabbit or muskrat furs. The same law applies to retailers who lie about fur being fake.

8 Lead Paint On Your Accessories

According to a study by The New York Times, many brightly colored fashion accessories that come into the US from overseas often contain lead-based paint and dyes. The exporting countries don’t have the same regulations as the United States, and their products could be making people sick. Colorful purses, wallets, hair accessories, and plastic jewelry could all possibly contain the toxic material. Touching the products and then touching food, scratching eyes, etc. could cause lead contamination in the body. Even if someone is exposed to trace amounts of lead, it can cause nerve damage and kidney failure. In 2010, a lawsuit was filed against multiple stores where lead was discovered in their accessories. Some of the stores involved in this lawsuit included Target, JC Penny, Kohls, Victoria’s Secret, Macy’s, Sears, and Saks Fifth Avenue. All of those retailers had accessories that contained lead. As of 2013, these same stores had their products tested again. They had become more diligent with checking the toxicity of the products they sell, as nothing contained lead. However, many consumers may still have lead-containing products in their homes. Hundreds of other retailers that weren’t included in the lawsuit could still possibly be selling such products. For example, Forever 21 wasn’t included in the lawsuit, so they don’t check the lead content of their products ahead of time before they try to sell it. They have agreed to recall anything that is brought to their attention.

7 Dangerous Working Conditions

In 2012, a garment factory called Tazreen Fashion caught fire in Bangladesh. Without the existence of fire safety laws, the company wasn’t required to provide smoke alarms or fire exits or have its employees perform fire drills. When the factory caught fire, the 11 members of the management were able to escape, while 112 women employed as seamstresses were engulfed in flames. Shortly after that, over 1,100 workers died in the Rana Plaza garment factory when the building collapsed. Again, there were no standards of what condition a building must be in to be considered safe for employees. It took all of these people dying before Bangladesh began creating standards for fire safety. Worker’s unions are illegal there, and the people running the factories were never held accountable for how they treated their employees. Despite the recent attention that has been given to the issues, there still remain multiple companies who continue to place their workers in awful conditions, simply because they haven’t been caught yet. Walmart and The Gap, two companies known for their cheap clothing prices, manufacture their clothing in Bangladesh. Rather than taking any responsibility for demanding mass amounts of clothing from the Tazreen Fashion factory, Walmart issued a statement to The New York Times that their own US-run stores take fire safety very seriously and that they will attempt to give education to their factories in Bangladesh.

6 Made To Fall Apart

“Fast fashion” clothing retailers like H&M and Forever 21 are constantly pushing new inventory every single month, which means that they demand faster production times. They also demand that costs stay low, so the factories use the cheapest fabric and thread available. There is simply not enough time to ensure that a piece of clothing is going to last for years when it’s being produced so quickly and with such low-quality material. Simon Collins, the dean of fashion at Parsons New School of Design, commented to NPR about fast fashion: “It’s just garbage. [ . . . ] You’re going to wear it on Saturday night to your party, and then it’s literally going to fall apart.” Brands like L.L. Bean have always strived to sell products that can last a lifetime. They are so confident in the quality of their US-made clothing, in fact, that they will allow you to return any of their items back, regardless of how many years it has been since you purchased it. However, buying brand-name clothing does not always mean it’s a good product. You may think you’re getting a good deal on high-end brands when you shop at outlet stores. In reality, the majority of clothing sold is actually cheap stuff manufactured specifically for the outlets. These clothes are usually on the same level as poorly made “fast fashion” clothes, so the brand name doesn’t always mean that you’re getting a better-quality product.

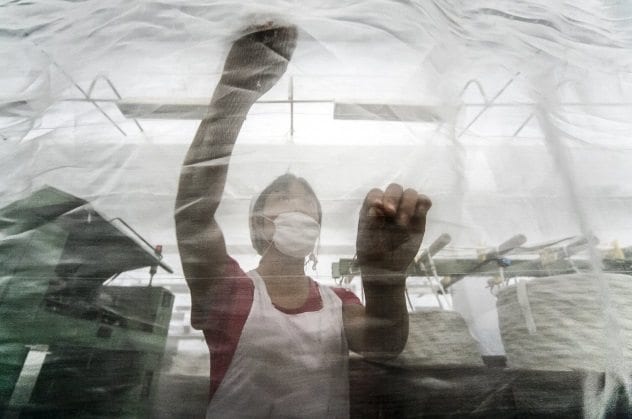

5 Dangerous Natural Fibers

According to the United States Department of Labor, employees who pick and manufacture cotton can be exposed to cotton dust, which floats in the air during processing. This dust contains bacteria, fungi, pesticides, and materials that can make someone very sick if they were to breathe it in. Some factories, especially overseas, do not have any safety regulations or mask-wearing requirements to prevent people from getting sick from breathing in cotton dust. The fear of natural fibers goes beyond the health of the workers. Just like any other plant, cotton can contain pesticides, which many people fear could linger on their clothing while it hangs in the store. This has lead to the “organic clothing” movement. Target, H&M, Nike, and Victoria’s Secret are just a few companies that came out with organically produced natural fibers like bamboo, soy, and hemp silk. However, just like produce in the grocery store, they charge higher prices for the organic clothing that promises your fibers will not contain any pesticides.

4 Work Faster Or Get Out

According to Human Rights Watch, the demand for nonstop production of clothing pushes workers to the limits. In one case, a woman had to leave work for a nosebleed that wouldn’t stop. Rather than getting blood on the fabric, she went straight to a doctor. Even though she provided her manager with a doctor’s note, she was fired immediately because her medical issue disrupted the speed of production. Despite the fact that the majority of people working in these factories are women, getting pregnant also means that a woman will become demoted to less pay and may lose her job. Overtime without increased pay is standard, pushing people to stay all hours of the night if they must meet a deadline for clothing companies. This also forces parents to stay in the factory longer, without being able to go home to see their family. A Norwegian documentary TV series called Sweatshop: Dead Cheap Fashion brought a group of young fashion bloggers to work alongside garment factory workers in Cambodia, so they could understand exactly where their clothing comes from. Many of them started out by brushing off the seriousness of the plight of the garment workers. However, even the most self-absorbed of these teens eventually ended up in tears, barely able to handle the injustice that the workers face.

3 Political Consequences

Cambodia exports billions of dollars of products every year. The top five products they export are all different types of clothing. Knit sweaters alone make up for 14 percent of the country’s entire economy. The United States consumes the largest amount of their exports, at 22 percent, but much of Cambodia’s clothing is distributed to other parts of the world. The other exports that Cambodia has to offer make such little money that the country would not be able to survive if their ability to make garments was taken away. While “fast fashion” and garment manufacturing in Cambodia is contributing to waste, poor labor practices, and corruption, the country still depends on clothing being sold to richer countries. Workers’ attempts to improve their situation have been shot down. Whenever someone has attempted to create a union to improve workers’ rights, they have been killed or injured. Clearly, those in power do not want unions to cut work hours, force them to pay for better working environments, or anything else because it would raise the production cost for the clothing. Cutting into the main source of income in Cambodia’s economy would cause even more political unrest. There seems to be no easy solution to the issue.

2 Mountains Of Waste

According to the Council for Textile Recycling, the United States alone produces 25 billion pounds of clothing waste every single year. A mere 15 percent gets donated to thrift shops and charities. The other 85 percent ends up in landfills. The vast majority of Americans who cannot afford or simply do not care about name-brand fashion shop for low-quality clothing from places like H&M, Walmart, and Forever 21. Once a cheap garment has fallen apart, people feel that they do not even have the option to donate their clothing to a thrift store, and it ends up in the garbage. Clothing waste increased by 40 percent between 1999 and 2009 and continues to grow every year. Even the clothing that is donated amounts to well over three billion pounds, while the entire US population is only 319 million people. In short, if companies stopped receiving shipments of new clothing from third world countries and sold their current stock for a year straight, clothing donations to thrift stores could very literally dress the entire country. As you can imagine, organizations like Goodwill get more donations than people can consume. Clothing is shipped to rag companies and also gets shrink-wrapped in huge cubes, or “bales,” and is sent to third world countries. Despite all of these ways to reuse clothing, literal tons are still being put into landfills.

1 Human Trafficking

In 2015, Patagonia, a clothing company known for their outdoor jackets and hiking equipment, decided to look deeply into the lives of the people who were making their clothing overseas. What they discovered was shocking. Despite the fact that garment workers in Taiwan make very little money, labor brokers will promise migrant workers that they can help them find a job—so long as they are indebted $7,000 in exchange for their employment. It takes two years of work for someone to make enough money to pay back the broker, but their term of employment only lasts for three years. So, if these people want a job again, they have to go through the process of paying the broker yet again, meaning that they only get to keep the salary of one out of every three years of work. Without any other options to turn to, many of these people fall into this endless cycle of human trafficking. Patagonia stepped in, and as of June 1, 2015, they forced the brokers to repay the debts of their workers and tried to restructure the standards of how their factories are run to the best of their ability. They are open to sharing their experiences, detailing their process of restructuring their overseas factory. It’s clear that thousands, if not millions, of people working for garment factories are victims of human trafficking, and the issue continues today. While Patagonia writes on their website that they are ready and willing to provide help to any other clothing company that is willing to go through their own investigations into human trafficking, it is clear that many corporations will choose to keep their profits, rather than spend valuable resources on human rights. Shannon Quinn is a writer and entrepreneur from the Philadelphia area. You can also find her on Twitter @ShannQ.