10Why It Was Built

The origins of Machu Picchu remain rooted only in theories. Its hidden beginnings endow the city with an awe-inspiring presence that can only be described as magnetic, and no real answer seems to be forthcoming any time soon. There are several popular theories. Perhaps the city was a sacred convent or a royal retreat. Some said it was the last Inca city to resist the Spanish, that it was constructed to represent a specific landscape from Inca myths, or that it was meant to honor the sacred river and mountains which surround it. Some of these have been disproven, like the suggestion that Machu Picchu was the last stronghold against the Spanish invaders, a fabled and legendary city called Vilcabamba la Vieja. In 1964, Gene Savoy found the real Vilcabamba some 130 kilometers (80 mi) west of the Inca capital of Cusco. The convent story fell through in 2000 when the on-site graveyard, previously thought to contain mostly women, turned out to have an equal number of both genders. Whatever the reason was, the site’s purpose didn’t last. A century after its construction, the city was abandoned.

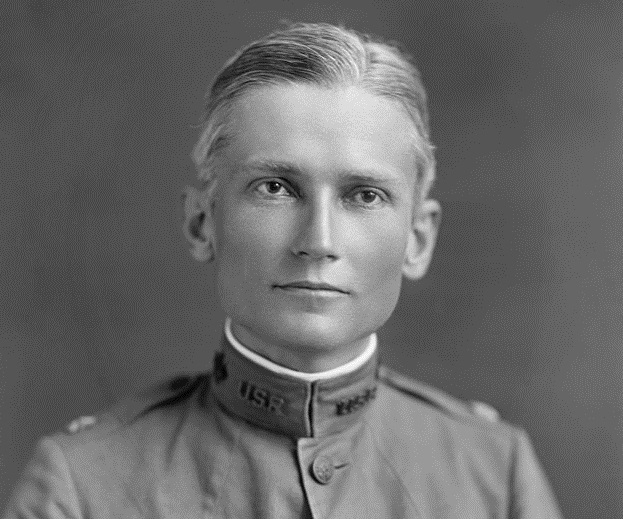

9Discoverer Doubt

While a Yale professor named Hiram Bingham (pictured) is generally credited with the discovery of the citadel, that honor is no longer so certain. While hunting for the fabled lost city of Vilcabamba, Bingham was led to Machu Picchu by farmers who lived nearby on the morning of July 24, 1911. Peruvian archaeologists claim that Bingham must’ve been aware that explorers from Germany, Britain, and the US had knowledge of the city before he did as they even drew maps of the place. Hawaiian-born Bingham never categorically stated that he was the first outsider to find the ruins, but he dodged giving credit to those explorers whose information had led him to Machu Picchu. This was not received well by the scientific community. Machu Picchu might have been the jewel in Bingham’s career, but it was also the thing that killed it. Because of the controversy surrounding how he came to discover it and his relentless self-promotion, academic reproach from his peers became so great that he never went on an expedition again.

8The Mystery Statues

Old documents started a mystery that people still wonder about today. These documents mention two statues, one made of gold and the other of stone, that once marked the grave of the Inca emperor Pachacuti at Machu Picchu. They were large and sacred, and they were also gone by the time Hiram Bingham showed up with his shovel. Paolo Greer, an American researcher, was busy tracking the paper trail of a looter named Augusto Berns (whom Greer believed had arrived at the city almost 43 years before Bingham) when he found some of Berns’s personal letters at the National Library of Peru. In these letters, Berns described how he witnessed a huge stone statue being pulled down by fellow looters in the hope of finding precious metals beneath the effigy. Greer believes this was the replacement for a missing golden sculpture mentioned in one of the most respected writings about the Andes people, the 1557 Narrative of the Incas by Juan de Betanzos, who wrote about the gilt copy of himself the emperor ordered to be erected at his grave. If the letters are to be trusted, the stone figure was still standing at Machu Picchu in the 1860s but vanished into a treasure hunter’s wheelbarrow around 1880. However, since no evidence of the statues’ existence can be found apart from these documents and the location of the emperor’s tomb at Machu Picchu is speculative, there are those who believe that they never existed in the first place.

7Terraces

What resembles velvety-green steps leading up to the city is in truth an integral part of what kept Machu Picchu together for so long. Most people have been taught that the over 700 terraces were purely used for agricultural purposes, but they also had the job of keeping the citadel anchored to the mountain. Their structure stabilized the slopes and prevented natural disasters that could possibly have unseated the city, such as landslides and flooding. They were designed to absorb water and let it drain safely away underground. The sheer height of the terraces not only gave the crops more sunlight but also protected them from getting washed away by water or avalanches. Essentially long boxes made from granite, these stones absorbed enough heat during the daylight hours to stay warm throughout the coldest of nights. This prevented roots from dying and also lengthened the growing season for crops such as potatoes, quinoa, and corn. Tests have also determined that the terraces, after being soaked, were able to remain moist for up to six months, essentially eliminating drought as a problem.

6The 16 Fountains

Machu Picchu has 16 attractive pools or fountains strategically built according to sacred beliefs. The fountains receive the water from springs located kilometers away thanks to an engineering system that collects and redirects the water back to the city. Called the “great stairway of liturgical fountains,” the 16 spouts create an air of tranquility with water flowing from one level to the next. Their purpose, like much of Machu Picchu, cannot be determined with certainty. However, since some are partially closed off, it’s possible that they served as a bathing area for the inhabitants and naturally also provided for the people’s domestic needs. The engineering marvel can handle up to 25 gallons of water per minute and was so well-built that almost 500 years later, the cascading waters still relax visitors today with their beauty and soothing sounds, just as they did for the Inca who originally lived there.

5The Rock Quarry

Something not often considered at Machu Picchu is its on-site stone quarry. It contains gems such as the Serpent Rock, a boulder decorated with snake reliefs, and other examples of the elite stonemasons plying their trade. One of these is a sizable piece of granite that had been worked to become a stairway but was never quite completed. Such pieces have spawned the theory that the lost city was still being constructed at the time when it was abandoned, and the site we know today was not completed. Hiram Bingham also left his mark on the quarry. Nearby is a rock that he tried to fragment with hot water, perhaps in an attempt to understand how the stonemasons split rocks. However, despite the interesting nuggets of granite and history that can be found at the quarry, visitors scarcely notice the large rocky space where it sits quietly between two of the city’s most visited areas: the Sacred Plaza and the Temple of the Sun.

4House Of The Emperor

The ruler at the time Machu Picchu was built was Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui. This powerful emperor was the one man responsible for turning his people into an empire that grew from Ecuador to Chile. The structure at Machu Picchu generally accepted to be the residence of the Inca leader can be found in the southwest sector of the complex. The royal compound is excluded from the nobility sector of the city, but the privilege of privacy might have something to do with that. Should the emperor have desired to go for a walk by himself, steps leading from the royal building to a private garden below gave him that seclusion. The location of his home gave Pachacuti the first taste of the cleanest water from the liturgical fountains. He could use this water to drink or to use in his own bathroom that even had a drainage system. No other private restrooms were found in the entire city. Several of Machu Picchu’s most sacred temples, fountains, and other buildings surround the emperor’s domain, perhaps to highlight the importance of the Inca leader.

3Earthquake Technology

The engineers of Machu Picchu built the citadel while keeping in mind that the land was (and still is) heavily prone to earthquakes. They employed several building techniques to add hardiness, but the simplest technique was perhaps the most brilliant: a construction method called ashlar. Precisely-fitting stone blocks without mortar allowed individual stones to move during an earthquake and settle back into their original places without bringing the building down. These blocks are famous for being so tightly interlocked that a sheet of paper can’t be inserted between them. It remains a mystery how the builders of Machu Picchu worked the stones so perfectly when their main material was granite, which is an exceedingly difficult material to work with even with modern technology. Inward and rounded shapes fortified buildings even more against the shakes; walls inclined slightly and entrances as well as windows were built narrower at the top than at the bottom. Corners were strengthened with L-shaped bricks and even the agricultural terraces kept the city together by preventing disastrous landslides during a seismic event.

2Intihuatana

Clinging to one of the slopes is a terraced building only accessible by two stairways. One is 78 steps strong and leads the visitor to one of Machu Picchu’s main attractions. At the topmost platform, facing the open skies, squats a granite carving with an odd shape and remarkable attributes. The so-called Intihuatana at its barest can be described as a waist-high block of solid stone with a pointy piece in the middle. No one entirely knows what the structure was for, but one can play with the facts. The corners of the four-sided centerpiece each point toward a main compass point: north, east, south, and west. Its north-to-east face captures the winter solstice and the summer solstice is at the east-to-south side. One of the ground block’s corners lengthens into a knob pointing at magnetic north. Most likely, Intihuatana measured and predicted the seasons for productive planting and harvesting and, because of its significance, it perhaps also doubled as an altar during key ceremonies. Such Intihuatana stones were found at places of importance throughout the Inca Empire, and the one at Machu Picchu ranks among the few not smashed by the Spanish conquistadors. But in 2000, the priceless artifact was disfigured when a crane fell on it during the filming of a beer commercial.

1Mass Graves

In 2008, 80 graves complete with skeletons and artifacts betrayed two long-hidden cemeteries near Machu Picchu. The magnitude of the discovery comes from the fact that human remains in the area, and Inca cloth in general, are really rare. Both were found in abundance at the approximately 500-year-old burial sites. Sadly, heavy looting had damaged most of the fabrics wrapping the bodies. Yet, despite the damage, researchers are confident that they’ll still be able to mine valuable information from the higher-quality textiles, such as the social standing of the deceased. Burial shrouds made from llama wool would indicate the lower classes, while any nobility would have been wrapped up with the fleece of the vicuna, a cousin of the llama. The corpses were buried in a sitting position and researchers are hoping to determine if they had helped build the famous lost city, their gender, diet, and cause of death. Who they were might narrow down what significance Machu Picchu held as the epicenter for trade and power in the region, a question that nobody had any hope of answering until now. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages