10 Gidim

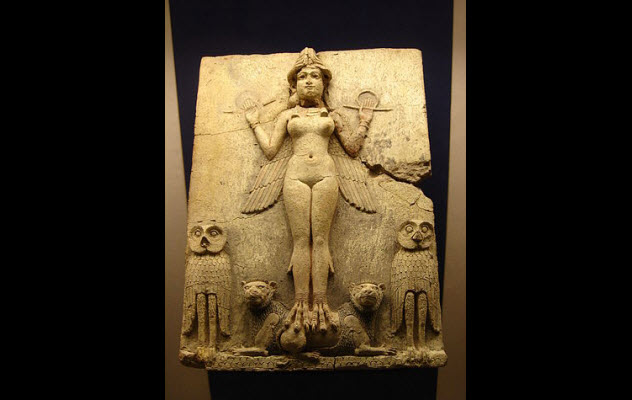

In ancient Mesopotamia, the living and the dead were closely connected. It was believed that mortality was one of the defining characteristics of humans. Anyone who died young had been cursed by the gods. Those who were healthy were watched over by beneficial spirits, and when that protection faded, so did life. Once a person died, they became a gidim, or “death spirit.” The spirit was a shadowy creature, sometimes appearing to friends, family, and loved ones and always recognizable as the person that they had been in life. However, the gidim didn’t appear at random. But it could be summoned by the living. Burial mounds in Mesopotamia were more than a place where earthly remains were interred for passage into the afterlife. The remains were also looked after in case they were ever needed to call a gidim back from the underworld. We don’t know what the process for properly interring a body was, but it’s believed to have varied according to the rank of the person. Kings and queens might have longer mourning periods than commoners, with their burial mounds often referred to as a “palace of rest” or “house of eternity.” The existence of the gidim in the afterlife was a dismal one, and it was up to the living to provide for the dead. Without gifts from the living, the gidim were condemned to eternal thirst and food that was bitter and almost inedible. Some stories tell of the gidim eating nothing but dust, existing in a realm ruled by Queen Ereshkigal and her consort, Nergal.

9 Assyrian Exorcisms

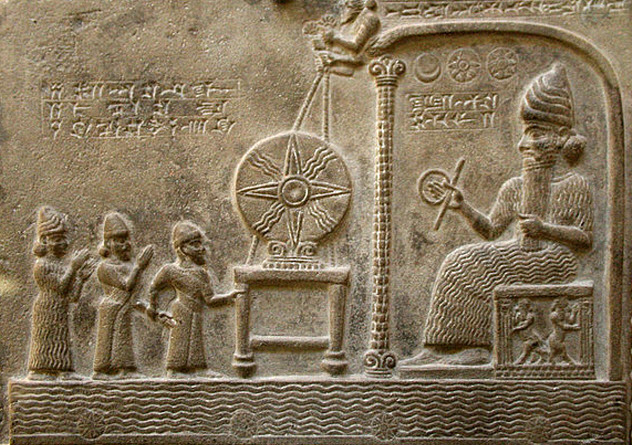

In addition to the half-human, half-supernatural beings that were thought to prowl through Assyrian homes, it was believed that anyone who hadn’t been honored with a proper burial would return to haunt the living as a ghost. Looking at the unburied, unprepared corpse of a dead man could allow the spirit to enter the body of a living person, but they were equally troublesome when they were haunting the living in their ghostly form. They were believed to suck the life force from the living, with strange rituals performed for those who were plagued by a ghostly presence. In some cases, the man who was haunted would be bathed, or the body of the person believed to be doing the haunting would be buried. In other cases, a ritual involving the god Shamash would be used. In this ritual, the Assyrian would first ask the ghost why they had returned and why they had targeted a particular person. Then the Assyrian would mix flour and leaven in an ox horn while a drink was poured in the name of Shamash. Finally, the mixture was put inside a hoof that came from a dark-colored ox, which supposedly put the ghost to rest. However, invoking the power of Shamash was no small request. One of the three major Mesopotamian deities, he ruled over the Sun during the day and the underworld at night. Shamash was believed to be the god that delivered the famous code of laws to Hammurabi. Shamash was also widely known as being above the petty and often unjust squabbles of the lesser gods. Another Assyrian belief painted ghosts as the harbingers of death, destruction, and tragedy. When a ghost appeared to the living, the house that it visited would be destroyed. If the ghost spoke to the living, those who heard it would die soon afterward.

8 The Ghosts Of Demons And The Childless

In ancient Babylonia, it was believed that ghosts walked through the night like the living walked through the day. They weren’t the incorporeal spirits that we think of today when someone mentions ghosts. Back then, it was thought that ghosts could possess the bodies of living animals and that the ghosts of the world’s demons had a particular affinity for possessing the bodies of birds. Evil spirits possessed wild dogs and lions, which were driven to hunt—and to occasionally hunt humans—because of the ghosts within them. One of the most powerful and dreaded of the Babylonian ghosts was the spirit of the woman who had died in childbirth, driven mad by grief and cursed to walk the night for the rest of time. Equally damned were those who died without having children, whether they were men or women. They, too, would be cursed to wander and wail during the night. To make sure that the spirits of parents, grandparents, and other ancestors were allowed to rest, the living—traditionally the oldest son—would leave food and drink for the starving, thirsty spirits. Without children to watch over them, the childless were forced to haunt homes and wander the streets, looking for anything to sate their appetites. Nighttime in Babylonia was a terrifying place, with many types of deaths forcing a person’s soul to remain in the land of the living and haunt empty buildings, possess the bodies of nocturnal creatures, and prey on those unfortunate enough to be traveling at night. These nighttime ghosts were the spirits of people who had died in the desert with their bones uncovered, who had their lives cut short in violent ways, who were executed as prisoners, who drowned and rose from the water to walk again, and who fell in battle and were left unburied.

7 Pliny The Younger’s Ghost Stories

Pliny the Younger was a Roman senator, born the son of a knight in AD 62. He lived through the reign of the tyrannical Nero, was taught by some of the most brilliant minds in ancient Rome, and left behind a ghost story among his many writings. In the first part of the story, he tells a tale of Curtius Rufus, an attendant to a Roman governor in Africa. One night, Curtius was out walking, and the ghostly visage of a beautiful woman appeared to him, telling him that she was a powerful spirit that watched over all of Africa. She told him of his future, revealing that he was to return to Rome, become elevated to a lofty position, and ultimately die on Roman soil. Eventually, he achieved the fame she promised, and when he returned to Carthage, he saw her again before he was overcome with an illness that led to his death, fulfilling the rest of the ghost’s prophecy. Pliny the Younger then tells the story of a notorious house in Athens where no one was able to live. Every night, the most horrible sounds would drift from the house. There was the rattling of chains, getting closer and closer to anyone nearby who listened. Those who tried to live in the house were often awakened by the ghostly specter of an old man—dirty, disheveled, and laden with chains. His presence even seemed to linger throughout the day, and ultimately, the house was all but abandoned to the ghost. Still, the owners tried to make money off the property. When the philosopher Athenodorus came to town looking for a place to stay, he rented the haunted house even after hearing the story of the ghost in chains. Setting up an office in the house, Athenodorus sat down to work through the night. Midway through, the sound of rattling chains filled the air. The ghost appeared, beckoning him, and Athenodorus followed. Dragging its chains, the ghost led Athenodorus through the house, and then suddenly, it vanished. Athenodorus marked the spot where the ghost had disappeared. The next morning, he asked the city magistrates to oversee an excavation. When they began to dig, they found the skeleton of a man, long dead and wrapped in chains. After giving the man a proper burial, the haunting stopped, and the ghost was laid to rest.

6 The Hand Of Ghost

In ancient Babylonia, seeing a ghost could be downright deadly. Dating to around the first millennium BC, ancient Mesopotamian texts on clay tablets went into great detail about illnesses and misfortunes stemming from the “Hand of Ghost.” Hand of Ghost seems to refer to both the illness and the method by which it was given. The most deadly diseases were believed to be passed on by ghosts of people who died of specific causes, such as drowning, immolation, or murder. When a family member died in such a way, it was cause for particular concern because of the connection that continued between life and death through the blood of relations. Sometimes, particular afflictions were linked to how the person died. For example, those who were afflicted with asthma or had difficulty breathing had been touched by the ghost of a person who had drowned. Supposedly, one of the first signs of a ghostly presence was a ringing in the ears. The eyes and ears were considered the most vulnerable parts of the living body. Wake up with headaches and a stiff neck, and you’ve likely been visited by a ghost. Ghosts were believed to reach out to the living through their dreams, so dreams of the dead—especially lucid dreams—needed to be fought with properly prepared elixirs and charms. The rituals to free someone from the Hand of Ghost were intense and could last up to six days. Often, there were offerings made to the dead and to the Sun god, to whom the living appealed to stop the ghost from interfering with them. Home and body were sanctified and cleansed with oils while incantations were repeated to help clear the ghostly influence from the mind. In extreme cases, when there were many symptoms that indicated a ghost was relentlessly pursuing someone, the ritual could include slicing open that person’s temple with a knife and bleeding him or her within the protected confines of a temple facing to the north.

5 The Roman Manes

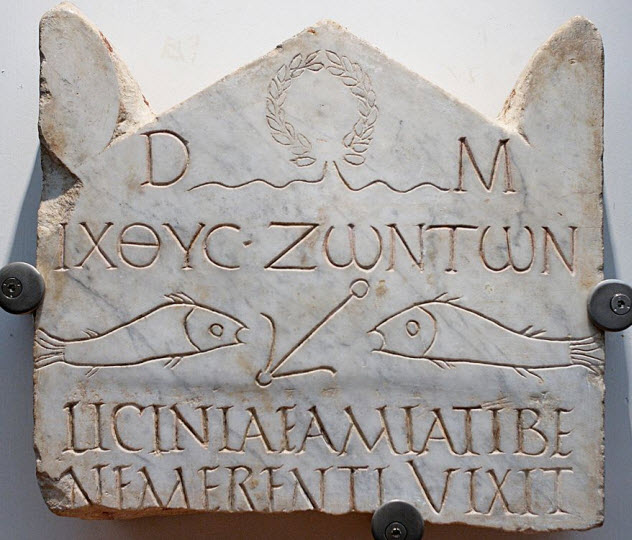

In ancient Rome, tombstones that bore Latin inscriptions often included the words dis manibus, meaning “to the divine manes.” The manes are thought to date back to the earliest beginnings of the Roman Empire. Although there are numerous mentions of them throughout Roman texts, they’re somewhat hard to define because religious beliefs kept shifting. Originally believed to be the spirits of deified ancestors, the manes were something between ghost and god. To understand the manes, we have to strip away modern Christian ideas and look at the worship of the dead with an open mind. Removing any notion of the afterlife and returning to a pre-Christian world, the manes become a sort of Everyman’s god. While most of the state gods were worshiped in temples and were the domain of state-sanctioned priests, the manes were worshiped in homes. They were spirits of recently deceased family members who remained in the home to stand guard over the living family members, to protect them, and to give assistance and guidance where they could. The manes were individual ghosts that acted in much the same way that gods did but on an individual scale. The worship of manes followed the same lines as inheritance. When a person died and passed on their estate to a child or another party outside of the family, that person also inherited the ghost of the dead. In some instances, creditors received financial fortunes after someone’s death and so inherited the manes, making the creditors obligated to worship the manes as though they had once been the creditors’ own flesh and blood.

4 Aibhill And The Worship Of The Banshees

The word “banshee” conjures up the image of a ghostly woman wailing the name of the next person to die. However, banshees weren’t always such dire harbingers. At one point, they were worshiped as goddesses. One of the most famous banshees is Aibhill, the ghost that haunted Crag Liath and the House of Cass. She was the one that appeared to Brian Boru in 1014, telling him that he wouldn’t walk from the battlefield that he led his men onto that Good Friday. The tradition of the banshee had been around for hundreds of years. Although we’re not sure exactly when or how it started, we do know that the banshee Catabodva was worshiped as a goddess of war for the Gauls in the early fifth century. As for Aibhill, she became a queen among the banshees, holding court over 25 other ghosts that foreshadowed death for those living in County Clare. In the days of the great Celtic clans, each one was said to have its own banshee. Like Aibhill, Eevul also ruled over a court of lower-ranking ghosts as she served the O’Brien family, although others seemed to live a more solitary existence. The banshee that roamed the mountains of Connemara wore a bright red cloak and sang rather than wailed, while the banshee of County Mayo was an old woman, clad in a dark cloak and uttering a wail that was heard long before she was seen. Ancient banshees had a much different way of delivering their messages, too. While today’s stories tell of banshees that cry and scream, the ancients would be seen washing the blood out of clothes or washing the blood from human heads and limbs before a battle.

3 Enkidu And The Sumerian Ghosts

The epic stories of Gilgamesh date back to at least 1800 BC, with an alternate ending appearing for Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld about 800 years later. In the original, Enkidu is long dead, having offended the dead so much they’ve decided not to let him go. However, in the alternate version, Gilgamesh prays for the release of his friend, and the Sun god grants his request. Enkidu returns from the netherworld and reports on the ghosts that he met there. Enkidu paints a gloomy picture of the dead living a dreary sort of existence that parallels their life among the living. They live among dark homes that no one ever leaves, forced to survive on dust and dirt. At first, Enkidu refuses to tell Gilgamesh what he saw, fearing that his friend will sink into a pit of dismay. (Gilgamesh doesn’t do that, but he is extremely disappointed when he finds out that ghosts don’t have sex.) When Gilgamesh asks about the afterlife of ghosts that lived in a particular way, Enkidu is specific. The ghosts of people who had seven or more children were quite comfortable, having plenty of children to make offerings of food and drink to sustain them. Those who had only two children ate only inedible food. The childless were condemned to starve and be completely alone. For people who suffered extreme injuries before their deaths, Enkidu reports that ghosts continue to live in whatever condition the body was in when it left the land of the living. The ghost of a leper continues to swell and rot, the ghost of a man savaged by a lion is still in pieces, and the ghost of a man who burned to death continues to burn. The ghosts also suffer or benefit from the actions they took while they were living. Those who ignored their duties to their family and to their ancestors wander in eternal torment while those who devoted their life to their god are rewarded by the grace of that god. Enkidu also mentions that the ghosts of stillborn children have the best afterlife. As they died in complete innocence, they “enjoy syrup and ghee at golden and silver tables.”

2 The Haugbui And The Icelandic Ghosts

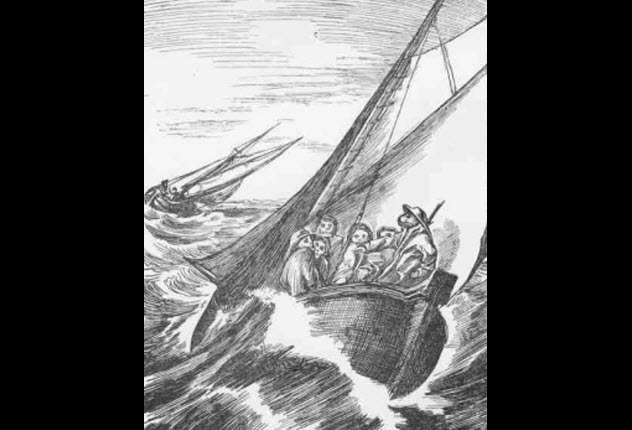

In ancient Icelandic and Norse folklore, ghosts are defined in a way that’s rather different from the rest of the world’s traditional views on the forms of spirits taken by the dead. Perhaps the most well-known is the draugr, a corporeal ghost that leaves its burial place and restlessly wanders. The draugr has a counterpart, the haugbui, and like the draugr, this creature retains its physical form. Unlike the draugr, the haugbui is confined to its burial mound, and its wrath is reserved for those who disturb the sleep of the dead or try to pillage its place of rest. The haugbui are frequently mentioned in the great Norse sagas, and some real-life precautions were taken to ensure that the deceased would rest peacefully. When a dead person was prepared for burial, his big toes were often tied together, needles were inserted into the bottoms of his feet, and open scissors were placed on his chest. As people were often prepared in their homes and it was well-known that a ghost could only enter the home again through the door from which it had left, many homes had designated “corpse doors,” which were used to take a body out and then sealed against reentry. Other Icelandic ghosts are defined in specific ways. The utburdur was the ghost of a baby, the fepuki was a ghost that could not rest because it kept returning to the money it had accumulated in life, and the skotta was an evil, potentially violent female ghost (with the male counterpart called the mori). The fylgja was a ghost that had attached itself to a certain person and often acted as that person’s herald, and the vokumadur was the name given to the first person buried in a newly established cemetery. According to legend and lore, the ghost of that person will protect the cemetery and its future inhabitants, and the person’s physical body will never decay.

1 The Ghosts Of The Cult Of The Dead

The ancient Celts had a huge number of rituals associated with worshiping ancestors and caring for the ancestral ghosts that they believed spent their afterlife around the family hearth. Some of the earliest traditions included taking the heads of enemies slain in battle and dedicating them to the ghosts of the great warriors and leaders in the family’s history. In places like Brittany, it was believed that the ghosts of the dead gathered at night around the fire in the hearth, seeking the same warmth and comfort they had known in life. Harvest festivals were also a way to appease ghosts that might be angry about the continued practice of sacrifice among the Celts. Lugnasad typically involved the ritual killing of a person whose sacrifice was meant to represent a corn spirit. Besides showing thanks for a good harvest, the festival and the sacrifice were also offered to the memory of those who had died for the continuing success of their people. That way, the living could avoid the wrath of an angry ghost. Traditions like the burning of the Yule log have been linked to the belief in family ghosts gathering around the hearth for the holidays while Samhain was traditionally the time for restless spirits to start walking the Earth. For the Celts, it wasn’t just the living who were responsible for caring for the ghosts of the dead. In Kilranelagh, County Wicklow, cups were placed in recesses built into the graveyard’s well every time a child under five years old was buried there. According to legend, it would be the child’s duty to tend to the other ghosts and bring them water in the cups left behind for them by their mourners. Read More: Twitter