10Ancient Civilizations Were More Connected Than We Think

Romans in China, Greeks in India, Africans in England—through a number of mechanisms, people of the ancient world got around more than we give them credit for. Other than a vague notion of the Silk Road, many have no idea how wide-ranging and enterprising some ancient civilizations were. There were, of course, the Phoenician explorers who likely circumnavigated Africa two millenia before Vasco de Gama. Carthaginians explored as far north as Greenland, as far south as Sierra Leone, and spread Mediterranean culture into Africa. Thanks to Alexander the Great, Hellenistic culture made it all the way to what is now Pakistan, India, and Afghanistan. After Alexander’s death, his generals divvied up the Macedonian’s conquests. This ushered in centuries of cultural transfusion during which entire Greek-style cities were built in Bactria (now Afghanistan). The Indo-Greek and Greco-Bactrian kingdoms brought together east and west with cross-cultural relics like statues of Buddha wearing a toga and the “Greek” friezes found in Pakistan. At least some Greeks converted to Buddhism and mixed their beliefs with Indian religions. The Romans got around, too. They drew troops from all over the empire, which included places like Mauritania, a land renowned for its horsemen. Serving in the Roman army, Mauritanians, like many other auxiliaries, fought everywhere from Britain to Dacia (now Romania, among others). The Roman military wasn’t the only site of unlikely cultural commingling, though. There is evidence for Roman trading outposts in the Kerala region of India from as early as the first century B.C. During Emperor Nero’s reign, Roman explorers following the course of the Nile may have traveled nearly to the Sudan-Uganda border. But it was in A.D. 166 that the Romans achieved something perhaps more incredible. Chinese-Roman trade goods had long been exchanged via intermediaries, likely piquing curiosity in both east and west. In A.D. 166, Roman ambassadors from the court of Marcus Aurelius traced the route of those goods and arrived in the Chinese capital. Take that, Marco Polo!

9Ancient Indians Practiced Plastic Surgery

Unlike the Greeks and Romans, many ancient Indian warriors didn’t wear protective helmets. Given the nature of ancient warfare, ears, noses, and other parts had a tendency to get lopped off. To address these traumas, Hindu doctors devised procedures which would not be entirely out of place in modern surgery. With warfare and harsh punishments for petty crimes taking the noses of many Indians, Indian surgeons became adept at performing rhinoplasty procedures. Indian surgeons cut a flap of skin from the patient’s forehead, which was then folded over the nasal openings to create the new nose. Hollow tubes were inserted to form the nostrils while the operation healed. Successful operations had been recorded by 500 B.C. A more horrifying but life-saving procedure was a form of suture Indian surgeons employed. Mending an intestinal or abdominal wound was tricky, because traditional needle-and-thread stitching might further perforate the wounded organs, preventing healing and inviting infection. The solution? Bengali ants. They bite anything they touch with clamp-like jaws. Surgeons drew flaps of the damaged organ together and carefully applied the ants, which functioned like modern-day surgical staples. The surgeon then cut away the ants’ bodies, leaving the jaws behind. The body’s immune system then slowly broke down the jaws as the wound healed.

8The Greeks And Romans Practiced ‘Gun Control’

It may be hard to believe if you’ve seen the recent 300 sequel, but Greek cities practiced a restrictive form of weapons control. Despite—or perhaps because of—the often bellicose nature of Greek society, weapons were prohibited in the public spaces of the ancient poleis. The ancient Greeks believed that “Laws rule alone. When weapons rule, they kill the law.” The ban on weapons helped ensure equality in a democratic or republican society. The possibility—or likelihood—of people using their weapons for intimidation was too great and would undermine civil society. If one was to be in the city, he ought to lay his weapons aside. Carrying weapons in the public assembly or agora (marketplace) was akin to violent subversion. How serious were the Greeks about “sword control”? Charondas, the Greek-Sicilian lawmaker who banned “revealed and carry,” returned from the countryside to the public assembly one day without removing his dagger. Granted, he had just been fighting bandits in the countryside, but Charondas’s law was as absolute as his commitment to it. Having violated his own law, Charondas publicly committed suicide with the dagger he failed to lay aside. And since for the Romans, “when in Rome . . .” was always followed by “. . . do as the Greeks do,” the Romans also banned weapons from their city limits. Carrying weapons within the Roman city center, or pomerium, was not just against the law, it was considered a religious crime as well.

7Nero Instituted Fire Codes And Firefighting Brigades

Talk about getting a bad rap. Popular history likes to remember the Roman Emperor Nero for two things he didn’t do: starting and celebrating a fire that destroyed much of Rome. To make matters worse, pop history forgets things Nero did do, e.g. implementing sweeping reforms to protect the city of Rome from future fires. After the fire of A.D. 64, which he didn’t start, Nero returned to Rome from his villa in Antium and organized a relief effort for the affected Romans. Nero’s real innovations came during the rebuilding phase, though. To prevent future fires from doing so much damage, Nero implemented stringent building codes. Prior to Nero, Rome was essentially a city-sized tinderbox. Narrow streets and wooden buildings constructed literally on top of one another allowed fires to spread out of control rapidly. The rebuilding that took place after the Great Fire followed Nero’s orders: widened streets, stone and brick construction, and height limits for buildings. Also, old aqueducts were diverted to better provide water for public consumption and firefighting. Perhaps most importantly, Nero formed a large brigade of night watchmen dedicated to keeping the peace and fighting fires. Thanks to Nero’s plans, Rome’s urban development became far more disciplined and carefully arranged.

6Rome Wasn’t The Sole Inventor Of Republican Government

Rome? Republic. Greece? Democracy. India? Maybe the crazed Thuggee priest from Indiana Jones and The Temple of Doom. To be fair, most of us didn’t receive much of an education about ancient India’s governmental structures. While ancient India certainly had its fair share of despots, it was also home to a number of small republics. A number of cities and towns in India embraced republican ideals, such as representation and collective decision-making, at about the same time Rome’s famous republic was founded. As far as we know, though, India’s and Rome’s republican principles were developed independently. The first records of republican-style government in India date to between 600 and 480 B.C. Despite their small size, some Indian republics even survived contact with Alexander the Great in the fourth century B.C. and the later conquest attempts of the famed Guptas. Even though they faced two of the greatest conquerors of antiquity, the Indian republics managed to retain their character of moderately enfranchised government until subversion and internal disunion did what Alexander and Chandragupta could not. Rather than force of arms, neighboring kings utilized spies and propaganda to foment disorder among republican rivals. Not a bad plan given the already somewhat fractious nature of the republics. Divided, the governing assemblies fell apart as rival factions asserted power via civil wars and alliances with external powers, who eventually rose to dominance.

5Roman Sexuality Wasn’t Progressive Or Accepting Of Homosexuality

Sexual license in Roman society certainly didn’t extend to anything similar to modern homosexuality. Asking an ancient Roman what he thought of homosexuality would be like asking him for his thoughts on the Internet. The Roman draws a blank in both cases, because neither one existed in ancient Rome. Roman sexuality wasn’t characterized by gender but determined by “role.” For a man, the “active” role—that of the penetrator—was generally acceptable, regardless of the gender of the penetrated. Being “passive” was considered aberrant for men regardless of the gender of their partner. As a result, it was entirely possible for man and wife to commit “monstrous” acts together. Cunnilingus is an excellent illustration of the Roman mindset. Though many today might argue the act of cunnilingus is far from passive on a man’s part, the Romans saw things differently. They believed that, in such an act, the woman was simply using her male partner’s mouth for pleasure, which was a failure of manhood. Fellatio was viewed the same way. A man performing oral sex on another person was “being used,” and it was considered a disgrace regardless of the gender of his partner. The Romans’ sexuality was far from progressive. The active-passive dichotomy created a highly restrictive sexuality. Women could only be penetrated, and men could only be penetrators. Nearly anything else was forbidden. Thus, while it was natural to want to penetrate anything and everything, a man could be considered deviant and feminine for wanting to pleasure his wife.

4Julius Caesar’s Last Words

Many believe that, upon his death at the hands of assassins, Julius Caesar uttered the famous words, “Et tu, Brute?” (“And you, Brutus?”) But the controversial dictator of Rome and lover of close-cropped haircuts said no such thing. William Shakespeare invented the line for his fictional version of Caesar to recite. But even in Shakespeare’s play, “Et tu, Brute?” is not Caesar’s last line. Caesar’s last line in the script is actually “Then fall, Caesar.” But what of the real, historical Julius Caesar? The man of historical fact was upper-class and well educated. In ancient Rome, that meant Caesar would have been conversant in Greek—unlike the Bard, who was famously unfamiliar with the language. The only ancient writer who mentions any last words, who himself was not even a contemporary of Caesar, suggests his life ended with a gasp of Greek directed at Brutus: “Kai su teknon?” However, it’s possible he may have simply been repeating gossip, since the phrase translates to “You, too, my child?” Rumors abounded regarding Julius Caesar, and one rumor suggested Brutus was Caesar’s bastard progeny. Alternatively, though less poetically, Caesar reportedly pulled his toga over his head as his assailants stabbed him to death.

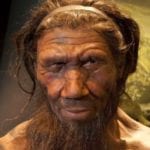

3‘Barbarians’ Were Simply People Who Didn’t Speak Greek

The thought of barbarians brings to mind violent, terrible figures both real (Attila) and imagined (Conan). But for the ancient Greeks, “barbarians” were simply people who could not speak Greek. The ancient Greeks thought the speech of foreigners resembled babbling (bar-bar-bar), and dubbed said foreigners “barbaroi.” In ancient Greece, the term did not have the connotation which it carries today (i.e., crude and uncivilized). The Greeks were not so chauvinistic as to ignore the glories of other civilizations like the Egyptian, Persian, etc. Those civilizations were recognized as magnificent, yet their non-Greek-speaking inhabitants would still have been dubbed “barbarians.” The ancient Romans used the term “barbarian” in much the same way as the Greeks. People not living within the Roman Empire and unable to speak Latin were referred to as barbarians. Only as antiquity gave way to the Middle Ages did the barbarian label really take on its now-familiar pejorative meaning of savagery. Western Christendom used the term to mark all those who fell outside its bounds, and everyone from Slavs to Arabs was considered barbarian. Those not conforming to Christendom’s standard were “uncouth” and “uncultivated.” The French writer Michel de Montaigne best summed up the historical meaning of the word when he wrote, “each man calls barbarism whatever is not his own practice.”

2The Romans Didn’t Invent Crucifixion

Though the Passion narratives have made execution by crucifixion synonymous with ancient Rome in many minds, the practice likely originated in Persia circa 500 B.C. From there, the extreme punishment spread to India, Egypt, Carthage, Macedonia, some Celtic lands, and Rome, among others. At least one Old Testament passage suggests that Biblical-era Jews employed a similar punishment as well, and Alexander the Great made an example of the vanquished town of Tyre when he crucified 2,000 of its male inhabitants in the fourth century B.C. In fact, it was the Carthaginians who perhaps made the most extensive use of crucifixion, and it is likely from them that the Romans adopted the practice. Unlike Carthage, who occasionally crucified its own losing generals, Rome typically did not crucify its own citizens. Considered to be the most extreme of death sentences, execution by crucifixion was a long, cruel, and painful punishment the Roman Empire reserved for its worst criminals, like Spartacus and his fellow rebels. The Romans, who were always fearful of slave revolts due to their extensive use of such labor, responded to the Spartacus-led revolt with one of the largest mass crucifixions in history, displaying 6,000 slave-rebels along the road from Rome to Capua in 71 B.C. Though crucifixion was considered too abhorrent to be used against Roman citizens, the practice was not officially abolished within the empire until A.D. 438.

1The Fall Of Rome Didn’t End The Empire

Supposedly, Roman domination ended in A.D. 476, when the city fell to German raiders called the Vandals. But Rome being sacked (again) was a minor blip on the Mediterranean radar. The empire’s capital, Constantinople, had long surpassed Rome in wealth, population, and political importance. By its “fall,” Rome’s importance had even been eclipsed in the west by Ravenna, the Western Empire’s capital. Another reason Rome’s fall wasn’t as catastrophic as imagined was the Gothic general Odoacer, who deposed the last Western Roman Emperor. He didn’t actually want to change much—he just wanted to be in charge. Odoacer made sure to acknowledge the true emperor in Constantinople and maintain the status quo. For the average Roman, life carried on as usual for decades after the final emperor had reigned. That’s because the “barbarians” who took over—Goths, Ostrogoths, and Germans—had long been part of the Roman Empire as client-states, an increasingly large portion of the Roman military, and quasi-citizens. When a barbarian-Roman coalition finally defeated the Huns in 451, it was incredibly difficult to tell where the Romans ended and the barbarians began. What ended the Roman Empire wasn’t foreign invasion but a series of civil wars that wracked the frontier. The Roman army with its barbarian weaponry, dress, and generals squared off against itself over and over, reducing the Western Empire into countless fractious kingdoms with only brief unity under a handful of warlords. Regardless of the West’s decline, the Eastern Roman Empire survived for another 1,000 years, ruling large portions of Italy at various points in that time. J. is a reader and a writer. You can reach him here.