10United States v. CausbyLandowners Don’t Own Airspace

Common law long held that property ownership extends to the space above and below ground. This right grants landowners, among other things, mining rights over their land. It goes back to at least the 13th century, referred to by the Latin phrase Cuius est solum, eius est usque ad coelumet ad inferos (“whoever owns the soil, it’s theirs, all the way to heaven and hell”). It changed in 1946 due to the deaths of a few chickens. Thomas Lee Causby owned a chicken farm near a North Carolina military airstrip. The sound of low-flying planes scared the chickens into running at the sides of the coops—usually to their deaths. After losing 150 chickens, Causby had to give up his farm, so he sued the government for compensation under the Fifth Amendment’s takings clause. The courts ruled that though landowners do own the air immediately above the property, they don’t own the air infinitely upward, as ad coelom had suggested. This changed the amount of space that a landowner owns above his or her property from “infinite” to the “safe distance as to which various aeroplanes could take off and land near the property.” That distance is 100–300 meters (300–1,000 ft), depending on the type of aircraft and whether it is day or night. The planes over Causby’s farm flew below that mark, so Causby received compensation from the government and won his case. But the government received a win in return, one that had little basis in the existing letter of the law but that enabled air travel as we know it. Without this ruling, airlines would have to apply for tens of thousands of permits for any long-distance flight.

9Nix v. HeddenTomatoes Are Vegetables

Botanically, the tomato is a fruit. A fruit is a plant’s ripened ovary, so the tomato is as much a fruit as an apple or a banana is—as is the pumpkin, the cucumber, the zucchini, and the chili pepper. But in the 1880s, the Port of New York was taxing tomatoes as vegetables. The Nix family, who imported lots of tomatoes, sued to win back all the taxes they’d paid. They had the objective definition of “fruit” on their side, or so they thought. The Court sided with Edward Hedden, the Collector of the Port of New York, declaring that tomatoes are vegetables. They decided to follow the spirit of the law rather the letter—most people consider savory items like tomatoes to be vegetables, so the law presumably included tomatoes under the “vegetable” umbrella. The tax law in question (The Tariff of 1883) is now long gone, of course, but the ruling has implications for related cases today. For example, the US imports pillows that are shaped like stuffed animals. Are they pillows, or are they stuffed animals? That question would be inane but for one fact: Pillows are tariffed, while stuffed animals aren’t.

8Welch v. SwaseyCities Can Limit Building Height

At the start of the 20th century, America fell in love with the skyscraper. Seemingly overnight, cities all across the nation were erecting towers that reached ever higher. In Boston, city ordinances limited the height of any building to 38 meters (125 ft), except in residential areas, where the height was capped at 30 meters (100 ft). So when wealthy Francis C. Welch wanted to erect a building just under 38 meters (124 ft), the city squashed his plan. He sued, claiming that the ordinance served no public good. It was written only to preserve the aesthetics of the city’s skyline. He lost his case. The Court declared that the statute wasn’t arbitrary or unreasonable, and they deferred to the lower courts, which had upheld the ordinance. To this day, any resident within a city of the US has to conform to building height codes. On a large scale, height restriction laws help air safety, as antennas thousands of feet tall obstruct aircraft. On a smaller scale, these codes prevent the overdevelopment imposing commercial structures in traditionally residential neighborhoods.

7US v. Ninety-Five Barrels, More or Less, Alleged Apple Cider VinegarDried Apples Don’t Make Cider Vinegar

This was one of the rare times that an item, rather than a person, has faced the ruling of a court. For this product misrepresentation case, neither the company in question nor any of its representatives were brought before the court. Instead, 95 barrels had to face the judges themselves. Or, rather, approximately 95 barrels—no one bothered to count the exact number, hence the odd title of the case. The year was 1924, and food regulation was still in its infancy. The Douglas Packing Company was selling a product called “apple cider vinegar,” but instead of making it from fresh apples as most manufacturers did, they made it from dried apples. Though the final product was barely distinguishable from the traditional alternative, the government accused the company of mislabeling it. The Supreme Court agreed. Mislabeling continued to be the FDA’s main target in the years that followed. In 1937, when a toxic supposed medication killed over 100 people, the FDA could only seize unsold bottles because it declared them mislabeled. The next year, the agency finally gained the power to review products before they went to market.

6Rowan v. US Post Office Dept.You Can Opt Out Of Junk Mail

The Postal Revenue and Federal Salary Act of 1967 required businesses to stop sending erotic material to individual households when asked. The appellants in this 1970 case—businesses that sent material, including porn, across the nation through the postal service—claimed that the restriction infringed on their free speech. The court disagreed. People have the right, as the statute said, to choose the type of material they want to enter their home. In fact, the court went further than that. People also have the right to reject any material at all, no matter the reason. The rights of any advertiser or solicitor end at the borders of a person’s property. The advertiser has the legal right to say what they want—but they have no right to do so in your house if you’d rather they not. So in the end, because a smut peddler was worried over his right to free speech, he ended up shooting the advertising industry as a whole in the foot.

5Hustler Magazine v. FalwellSatirists Are Not Civilly Liable

The following is probably the most famous case on this list. It’s known to anyone who has seen the movie The People vs. Larry Flynt. Watch this video on YouTube In 1983, Hustler published a parody ad featuring the reverend Jerry Falwell discussing losing his virginity. (In the parody, he lost it to his mother; he was evidently the last man in town to sleep with her.) While the First Amendment lets magazines print such nonsense without fear of criminal prosecution, people can sue the publication for defamation and related offenses. Falwell sued Hustler for emotional distress. He won in a lower court, but the Supreme Court overturned the ruling. This case was a sort of inversion of Rowan. Rowan held that a person can personally refuse exposure to obscene material meant for wide distribution. In this case, the court ruled that a person could not prevent obscene material which depicted them personally from being distributed widely. Nor can they claim personal damages from the public’s exposure to the material if it is created in the spirit of parody. The People vs. Larry Flynt dramatizes much of the case’s proceedings, but the closing arguments made by Flynt’s lawyer at the end of the film reproduce the actual court transcript verbatim. The lawyer, Alan Isaacman (played by Ed Norton in the clip above), argues that if Falwell could sue Hustler for the ad, politicians could equally well sue Doonesbury cartoonist Garry Trudeau or Johnny Carson from The Tonight Show. This landmark ruling was a huge win for comedians across the country—and for all of us.

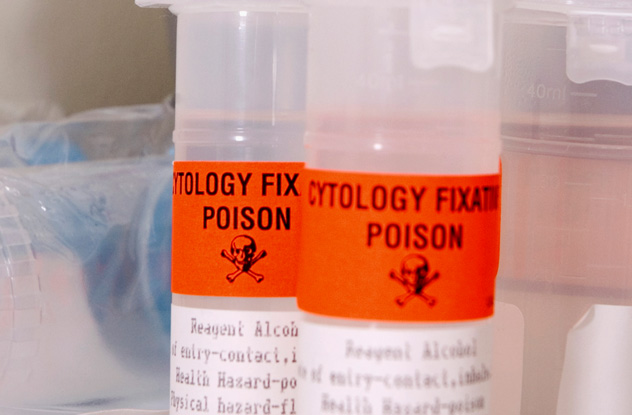

4Bond v. United StatesThe 10th Amendment Protects Individuals

In this recent case, microbiologist Carol Bond poisoned her husband’s lover with toxic chemicals. She got caught (before her plan worked) and was indicted under the federal Chemical Weapons Convention Implementation Act. This act implemented the US’s participation in an international arms treaty (the same treaty that Syria famously had to enter into in 2013). Bond sued the US government for prosecuting her, claiming that enforcing domestic prosecutions through an international treaty violates the 10th Amendment. The 10th Amendment clarifies that the federal government has no power other than what the constitution explicitly assigns it; other powers belong to the states or to citizens. The Supreme Court unanimously agreed that Bond had standing to sue. This was a groundbreaking precedent. Until this point, the 10th Amendment had only come into play when states claimed that the federal government usurped their authority. From this point onward, individuals can sue under the 10th Amendment as well. The justices sent the case back to a lower court, and when it returned in 2014, they sided with Bond. The federal law was written to govern how rogue states use weapons, not to punish scorned spouses. As Justice Roberts wrote, “The global need to prevent chemical warfare does not require the Federal Government to reach into the kitchen cupboard, or to treat a local assault with a chemical irritant as the deployment of a chemical weapon.”

3Astrue v. CapatoNo Benefits For Posthumous Conceptions

Robert Capato died of cancer in 2002, but in the year leading up to his death, he regularly deposited his semen at a sperm bank. His widow, Karen, gave birth to a set of twins 18 months after Robert’s death. Karen sought survivor benefits from the Social Security Administration for the children, but she was denied. The twins did not fit the definition of “child” under the Social Security Act. The definition covered natural-born children, adopted children, and step-children, but it said nothing about children conceived artificially after the father’s death. Mrs. Capato argued that the twins didn’t need to meet any special requirements. They were the biological offspring of two legally married persons. Such people, Karen asserted, are legally children and are automatically entitled to Social Security children’s survivor benefits. The court, however, unanimously rejected her argument. The rejection was very similar to Nix v. Hedden in valuing the intention of the law’s writers over technical definitions. The court said that the legislators, writing in 1939, could not have even imagined this unusual birth, so their law could not have possibly aimed to include it. For Social Security benefits to go to children like Mrs. Capato’s, Congress has to amend the law.

2Coates v. CincinnatiLaws Can’t Ban Annoying Speech

Cases important enough to make it to the Supreme Court usually involve clearing up the definition of a law. In this particular case, the court was asked to define a single word: “annoying.” In 1956, the city of Cincinnati passed an ordinance making it illegal for a group of three or more people to gather on a sidewalk for the purpose of “annoying” others. Then came the social upheaval of the ’60s. When local police used this ordinance to shut down protests, a group of students challenged the law all the way to the Supreme Court. The students argued that it’s impossible to clearly define what one person might find “annoying” and what another might not. The law is therefore unconstitutionally vague. The Court agreed, further declaring that the law’s potential for violating free speech was immense. As the ruling summed up, “The ordinance before us makes a crime out of what under the Constitution cannot be a crime. It is aimed directly at activity protected by the Constitution. We need not lament that we do not have before us the details of the conduct found to be annoying. It is the ordinance on its face that sets the standard of conduct and warns against transgression. The details of the offense could no more serve to validate this ordinance than could the details of an offense charged under an ordinance suspending unconditionally the right of assembly and free speech. The judgment is reversed.” Since Cincinnati lost the power to shut down peaceful public protests due to individual complaints, no other city could bring forth a similarly vague ordinance. This kept the American political landscape dynamic, exciting, and free from interference from 1965 onward.

1American Broadcasting Companies v. AereoWeb Retransmissions Are Public Performances

The service Aereo let subscribers watch broadcast networks (NBC, CBS, ABC, etc.) from their computers, tablets, or smartphones. Subscribers could also record shows to watch later—they could watch network shows anytime without buying TVs, DVRs, cables, or antennas. The service treaded some tricky legal ground. On one hand, all of the content that it carried was free-to-air. Any individual with their own equipment can legally replicate Aereo’s services on a personal level without paying networks anything. One the other hand, copyright law applies differently when you broadcast material to large groups of people. In such cases, the broadcast counts as a “public performance,” and you owe the copyright holder royalties. That’s why a cable company must pay networks when it carries their channels. Aereo claimed that it wasn’t a cable company, it didn’t broadcast to large groups of people, and its signals were not public performances. The company assigned each user his or her own antenna, so each signal went to a single person as a royalty-free “private performance.” Aereo argued that it was not broadcasting copyrighted material at all. It was renting equipment to users, who legally transmitted free TV channels to themselves for their own personal use. A lower court agreed with Aereo’s arguments, but the Supreme Court didn’t. In June 2014, it ruled that Aereo was infringing on the networks’ copyright. The company suspended services soon after. The FCC has responded to the verdict by considering changing the rules about how video is transmitted over the Internet. Under revised regulations, Aereo and similar services could return as legal competitors to cable and satellite providers. They would pay royalties but bypass the existing transmission system, much like Netflix. They may even move beyond broadcast channels and let users pay for premium channels individually, offering an alternative to the monopoly that cable companies sometimes hold. Damien B. is a part-time writer and basketball lover who is interested in history, politics, crime, and of course basketball.