10Dinosaur Eggs Were Colorful

Dinosaurs were a lot more colorful than we give them credit for in horror movies. You probably already know that some dinos sported flamboyantly hued feathers, but now we have strong evidence that even their eggs looked fabulous. Oviraptor eggs, for example, were a soothing greenish-blue, according to a 67-million-year-old clutch of eggs found in China. Most fossilized dinosaur eggs have been stained dark as a result of minerals seeping into the shell over time. However, the eggs in this particular clutch were pale and relatively untainted, allowing scientists to identify the pigments biliverdin and protoporphyrin. These are the same pigments that produce the beautiful colors in the eggs of emus and cassowaries—two really old birds, evolutionarily speaking. At first, it might seem like colored eggs would be easier for predators to spot, but it’s actually just the opposite. Many dinosaurs kept their eggs in earthen, grassy nests, where a white egg would stand out like a sore thumb. But verdigris eggs would have blended in perfectly, allowing mama dinos to leave their eggs safely camouflaged while they sauntered off to catch a quick meal.

9Archaeopteryx Had Feathery Trousers

First discovered in Germany in 1861, Archaeopteryx is a milestone species because it represents the transition between dinosaurs and birds. Its teeth, claws, and beady eyes clearly identify it as a dinosaur, but its bird-like feathers show a clear link with modern avians as well. For a long time, paleontologists weren’t sure whether Archaeopteryx had feathers all over its body or just on its wings. But recently, a surprisingly intact new fossil (a total of 11 have been found so far) revealed plumes of feathers running down its legs. Thanks to its thick feather-shafts, most scientists do think Archaeopteryx could fly, but the newly discovered leg feathers wouldn’t have played a great role in that. Instead, the lower-body fluff might have served several other functions, including insulation and camouflage. It’s also possible that the pennate feathers evolved for display. The feathers found lining Archaeopteryx’s body are symmetrical. Which sounds great, but it’s actually asymmetrical feathers that are perfect for flight. So, Archaeopteryx probably evolved feathers to entice mates or communicate, which were then gradually “recruited for aerodynamic functions.”

8Atopodentatus Unicus Had Vertical Zipper Teeth

The time of the dinosaurs spawned some truly weird and horrific mouths, but Atopodentatus unicus is in a class of its own. Its mouth is so bizarre, it was actually named after it—Atopodentatus roughly translates as “weird teeth.” Around 3 meters (9 ft) in length, Atopodentatus was equally comfortable on land or in the seas. Lacking the hydrodynamic advantage of other sea monsters, Atopodentatus made up for it with a mouth full of needles. But what’s really weird is that some of those needle-like teeth were set vertically in its ugly face. In other words, its mouth looked just like a zipper. Not subscribing to the notion that less is more, Atopodentatus was also equipped with a relatively standard set of chompers spaced across a conventional lower and upper jaw. All in all, the terrifying marine reptile boasted about 400 hypodermic teeth spread across its multiple mandibles. Sadly, while that sounds fearsome, scientists believe Atopodentatus was a bottom feeder and used its vertical teeth as a filtering screen rather than a tool for terrorizing smaller creatures.

7The Crowned Triceratops

With three massive horns on its face and a shovel for a forehead, you can’t get much cooler than a triceratops. Except the Cretaceous totally did, cranking out the closely related Regaliceratops peterhewsi, colloquially known as “Hellboy” for the small horns above its eyes. Regaliceratops translates to “royal horned face,” while the creature’s surname honors Peter Hews, the amateur fossil hunter who first noticed its ancient remains. Hews made his serendipitous discovery when he spotted a horn sticking out of a riverbank in Alberta, Canada. The specimen was airlifted to a museum while still encased in its limestone prison, and scientists subsequently spent two and a half years slowly chipping it down to a more recognizable form. The regaliceratops is weird for two reasons. Firstly, its horns are seemingly anachronistic. The triceratops usually had large brow horns and a smaller nose horn, whereas the regaliceratops had short brow horns and a huge nose spike, just like a separate line of dinosaurs that died out two million years earlier. Secondly, its shield of a forehead isn’t frilled, but edged with pointy extensions that gave it a crown-like appearance (hence the name).

6Synapsids Push Back The Nocturnal Timeline

Around 300 million years ago, before even dinosaurs showed up, Earth teemed with synapsids: prototypical mammals that bore a superficial resemblance to lizards. These odd mammal precursors lived 100 million years before our small furry ancestors scurried underneath dinosaur noses. And, according to their fossils, they were nocturnal. Researchers usually work out whether a species was active during the day or night by looking at eye size. Large eyes are indicative of a nocturnal lifestyle, whereas smaller eyes indicate activity during the day. Obviously, eyes don’t survive the fossilization process, but a bony ring that forms around the eye socket is usually a good indicator of size. And the bony rings around synapsid eyes indicate that they mostly operated at night, which paleontologists found puzzling. Previously, the conventional wisdom held that the earliest mammals became nocturnal to avoid dinosaurian detection. But the night-owl synapsids show that nocturnal behaviors evolved long before dinosaurs were around to worry about. In fact, even apex predator synapsids like the massive, sail-backed dimetrodons were nocturnal, suggesting the behavior did not evolve as a defensive strategy at all.

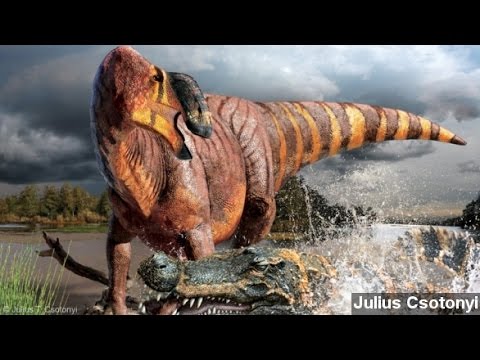

5Rhinorex’s Giant Nose

Rhinorex means something like “King of the Noses” and Rhinorex condrupus doesn’t disappoint. In an unlikely twist, paleontologists found its mostly complete skull in storage at Brigham Young University, where it had been largely forgotten since the ’90s. After slowly digging it out of a block of limestone over the course of two years—a task which they liken to chiseling a cranium out of a driveway—the paleontologists were delighted to discover they had a whole new species on their hands. Rhinorex condrupus is part of the hadrosaur family, consisting of dinos with prominent bony crests atop their heads. However, the rhinorex eschewed the distinctive crest, swapping it for a truly legendary schnoz. The odd dinosaur and its crested brethren roamed the primeval wilds of Utah around 75 million years ago, during the Cretaceous period, where the Brigham Young specimen was possibly killed by a huge ancient crocodile. No one’s sure why the rhinorex’s proboscis is so pronounced, but it probably has nothing to do with a sense of smell. Instead of an olfactory advantage, the nose might have been used to attract mates, because you know what they say about guys with big noses.

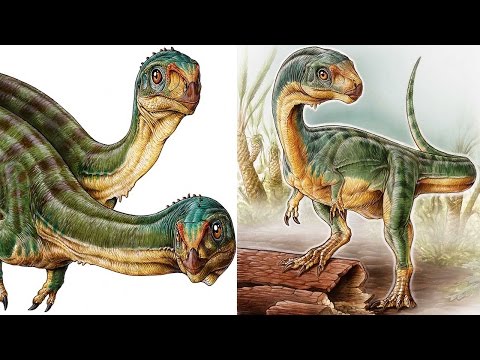

4The Platypus Of Dinosaurs

The T. rex has become a pop culture icon due to its terrifying awesomeness. Its evolutionary family includes some equally horrific relatives—but also at least one goofy cousin that probably wasn’t invited to many reunions. The Chilesaurus diegosuarezi is truly the platypus of dinosaurs, in that scientists responded to both with stunned disbelief. Just like its far-removed Australian counterpart, the Chilesaurus’s anomalous body fooled some into thinking it was a mishmash of different animals. From its pelvis to its limbs, from its fingers to its claws, almost every body part could have, at a glance, come from a separate dinosaur. And even though it’s closely related to the fearsome T. rex, the Chilesaurus was a devout vegetarian. Aesthetically, its beak-like mouth was rather less threatening than its cousin’s toothy snout. It was also decidedly smaller, with a maximum length of 3 meters (10 ft) and an average size no larger than your Thanksgiving centerpiece.

3The Earliest Snake Ancestor

Some creatures have been dramatically altered by the gradual, unceasing effects of evolution. Others, at least superficially, have remained unchanged. The progenitor of all snake-like things, which was recently discovered to have thrived in damp southern climes almost 130 million years ago, looked not too dissimilar from its modern descendants. Well, except for its hind limbs, that is. Yes, ancient snakes had tiny, adorable legs which tapered into bonafide ankles then diverged into individual toes. The proto-snakes that followed thereafter were probably nocturnal and had needle-like teeth with which to subdue prey before gulping them down like modern snakes. It doesn’t appear that these early specimens strangled their victims a la boa constrictors, so this deadly technique must have been developed further down the timeline. Surprisingly, scientists don’t know much about snake evolution, and they knew considerably less before this study. To reveal the amazing legged serpent, researchers employed fossil evidence, anatomic knowledge, and a recreation of ancient snake behavior.

2The Bat-Winged Early Bird

When paleontologists dusted off a mid-to-late Jurassic period creature and found it had wings, they were understandably stoked. As one of the earliest birds, the specimen, eventually named Yi qi, would offer a glimpse into the evolution of modern avians. But, to general surprise, the Yi qi had wings quite unlike modern avians. While reconstructing the partial skeleton unearthed in China, researchers found a patch of preserved membrane between its spindly fingers, leading them to conclude that it had creepy, bat-like wings. Or maybe even flaps like a flying squirrel. But definitely not bird wings. The Yi qi did have feathers, but apparently not where they counted most. Its clumsy wings offered none of the aerodynamic perks of feathered appendages, and it probably wasn’t able to fly at all. Instead, it used its claws to climb trees before using its nasty membranous flaps to glide short distances between arboreal perches.

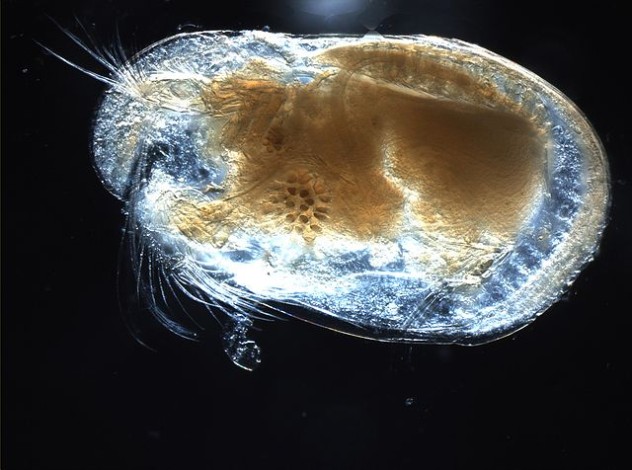

1The Ancient Creature Smaller Than Its Own Sperm

The extant ostracods are tiny crustaceans about 1 millimeter (0.04 in) in length. They’re super prolific, look like plankton with whiskers, and one of their ancestors had some truly spectacular sperm. In an extraordinarily fortunate stroke of luck, researchers found a batch of 16-million-year-old sperm, perfectly preserved inside a female ostracod’s reproductive tract. Soft tissues like sperm are ridiculously fragile. So to stumble upon a specimen of such detail and age is almost unheard of. To find that the specimens involved were immortalized post-coitus considerably boosts their rarity. And the preserved sperm were bizarrely, comically large, up to 1 centimeter (0.4 in) in length, which makes them considerably longer than the ostracod itself. It’s pretty rare in nature for an animal to boast sperm larger than itself, although some moths and fruit flies also share in this distinction. Sadly, scientists aren’t sure why these unassuming animals pack .50-cal ammo for gametes, but they are duly impressed.