Police have estimated that up to half of the art sold on the international market may be forged. Major museums are estimated to hold collections that are about 20-percent fake. In April 2018, one museum in France discovered that 82 of their 140 Etienne Terrus paintings were counterfeit. The forgeries were only spotted when an eagle-eyed visitor noticed that some of the buildings featured in the paintings were built after the artist’s death. Oops.[1] Artists often receive only a small fraction of the hammer prices for valuable artworks. Sometimes, those artists decide to fight back.

10 Han Van Meegeren

In 1932, Han van Meegeren, stung by criticisms that his work was “unoriginal,” decided that he would create a new and original work by the great master Johannes Vermeer. He told himself that once the painting was accepted by leading scholars, he would denounce it as a hoax. He created his painting, called Supper at Emmaus. He used genuine 17th-century canvas and only pigments that would have been available at the time. He added Bakelite to the paints, which made them dry rock-hard, giving the impression of great age.[2] It was proclaimed a masterpiece and purchased by a Dutch gallery, becoming the highlight of their exhibition. The moment for Van Meegeren to announce his fake came. And went. He decided, instead, to work on another one. And another. And another. In 1945, Van Meegeren made the mistake of selling one of his Vermeers to the Nazi leader Hermann Goering. When the war ended, he was charged with treason for selling a work of national importance to a member of the Nazi party. Van Meegeren was forced to admit, in his defense, that the work was a forgery. He became famous overnight, not only as the world’s best art forger but also as “the man who swindled Goering.” Without this reluctant confession, Van Meegeren might have continued to fool the art world forever.

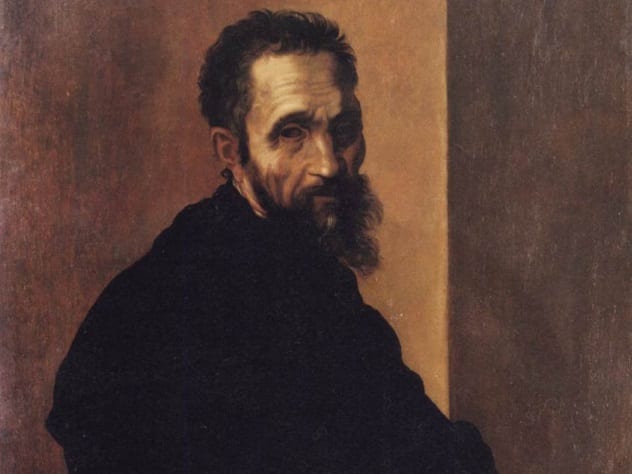

9 Michelangelo

Michelangelo started his career as an art forger. He created a number of statues, including one called the Sleeping Cupid (or simply Cupid ), when he was working for Lorenzo di Pierfranseco. Di Pierfranseco asked Michelangelo to “fix it so that it looked as if it had been buried.” Di Pierfranseco intended to sell the sculpture as an ancient work, not knowing that an authentic work by Michelangelo would one day command a much higher price. The piece was sold to Cardinal Raffaello Riario, who, on discovering that the piece had been artificially aged, demanded his money back from di Pierfranseco. He was, however, sufficiently impressed by Michelangelo’s skill that he did not press charges for fraud. He allowed Michelangelo to keep his fee and invited him to come to Rome to do a spot of work at the Vatican, which turned out rather well for both of them. Michelangelo’s Sleeping Cupid was later purchased by King Charles I of England, where it is thought to have been destroyed in a palace fire in 1698.[3]

8 Reinhold Vasters

Reinhold Vasters was an accomplished German goldsmith in his own right. He was also a very accomplished forger in, well, not his own right. Many of his pieces have turned up in private collections and museums, and it is certain that there are more waiting to be discovered. Vasters had won prizes for his own work, including at the Great Exhibition in London in 1851. He specialized in creating religious pieces in gold and silver. It is believed that he began to create his forgeries in order to support his family after the death of his wife.[4] He seems to have been especially prolific in faking Renaissance jewelry, with several pieces turning up in the Rothschild collection. As of 1984, the Met Museum had uncovered 45 fakes in their own collection which were created by Vasters, including the Rospigliosi Cup, which was previously attributed to Benvenuto Cellini. But the Met is not alone. The Walters Museum purchased Vessel In The Form of a Sea Monster (pictured above), which they believed to have been carved by Alessandro Miseroni and mounted in gold by Hans Vermeyen in the early 17th century. But it turned out to be another Vaster piece. The forgeries were not discovered until 60 years after Vaster’s death, so there is no way to tell how many he created, which must be a little nerve-wracking for collectors.

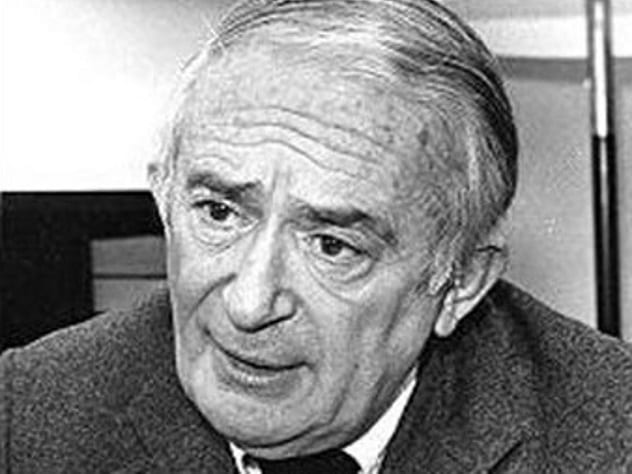

7 Elmyr De Hory

Elmyr de Hory was a faker in every possible way. He moved to the US after World War II, portraying himself as a dispossessed Hungarian aristocrat who had survived a concentration camp and was now forced to sell off his family heirlooms to survive, none of which is provable or likely. It is claimed that he sold over 1,000 forgeries during his career, many of which have not yet been uncovered.[5] After failing in his career as an artist, de Hory sold a pen and ink drawing to a woman who “mistook it” for a Picasso, and a new career was born. He began to sell more Picassos, claiming that they were part of his family collection. He forged works not only from Picasso but added in Matisse, Modigliani, and Renoir, among others. However, suspicions were raised when he sold a “Matisse” to the Fogg Art Museum and followed it up by offering them a “Modigliani” and a “Renoir,” which all appeared suspiciously similar in style. In 1955, de Hory was charged with mail fraud after selling a piece of art via the post. However, he continued his career, moving from city to city selling off his “family heirlooms.” De Hory’s career came to an end after partnering with Fernand Legros. As de Hory was now known in the art world, he “retired” abroad, and Legros sold his paintings and took a (very) generous cut. Legros was not a careful man, however. He sold 56 forgeries to a single Texan oil magnate, who did not take the discovery well. The affair created worldwide interest in de Hory, and he became a celebrity. Unfortunately, the game was up when he was ordered to be extradited, and he committed suicide in 1976 rather than face jail. Ironically, the work of Elmyr de Hory himself is now sought after, and “fake forgeries” have begun to appear in auctions around the world, with other artists pretending to be de Hory pretending to be someone else.

6 Robert Driessen

Robert Driessen began his art career selling tourist art pieces in Holland and then moved on to painting “in the style of” other artists. It wasn’t long before he was painting and sculpting outright forgeries. Driessen is particularly known for his copies of the work of Alberto Giacometti, whose art can sell for millions of dollars. The profession of forger can be a very lucrative one, and for a time, Driessen became extremely rich. It is believed that he earned millions of dollars from his artworks.[6] Robert Driessen moved to Thailand in 2005 after a warrant was issued for his arrest in Germany. He claims that he was paid to skip the country by art dealers who had made millions selling his work and didn’t want to be involved in the scandal. It is estimated that there are still over 1,000 Driessen forgeries in circulation, most of which have not yet been discovered.

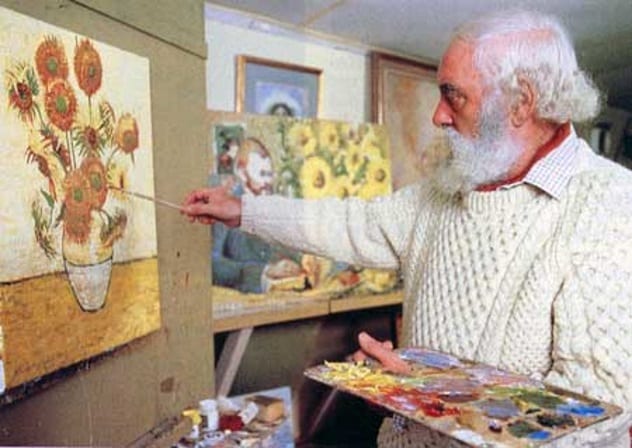

5 Tom Keating

Tom Keating has been described as the most important forger of the 20th century. He specialized in producing watercolors by Samuel Palmer and oil paintings by old masters. Having failed to achieve fame as an artist in his own right, Keating turned his back on the art gallery system, which he regarded as “utterly rotten.” He believed that galleries and dealers were taking advantage of artists and making millions from their efforts, while paying the artists a pittance. His forgeries were a means of redressing the balance.[7] Keating planted “time bombs” in all his pictures, writing rude comments on the canvas in white lead before he began the painting. When the painting was X-rayed, the messages would show up. He also included obvious mistakes in the pictures and used materials not in keeping with the period. He even painted one picture backwards! Anyone, except a greedy art dealer with an eye to making a fast buck, should have been able to spot the forgeries. But they clearly didn’t, and Keating is estimated to have created over 2,000 pieces “in the style of” 100 different artists. Keating and his partner, Jane Kelly, were finally arrested in 1977, when 13 very similar Samuel Palmer watercolors aroused suspicion. Kelly pleaded guilty. However, Keating’s trial was halted due to his ill health. He went on to make a number of TV appearances and write a book about his forgery career before passing away in 1984.

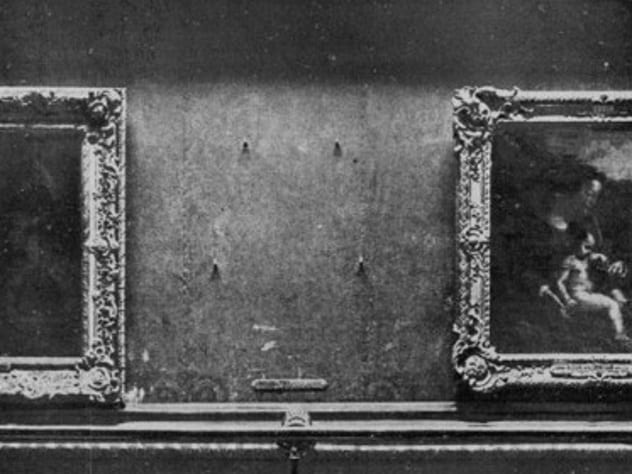

4 Yves Chaudron

Yves Chaudron was a French forger who is believed to have made six copies of the Mona Lisa as part of a conspiracy to steal the original. The plan was to steal the da Vinci masterpiece from the wall of the Louvre and then sell the six copies to prospective buyers, who would each believe that they had bought the stolen original. And, of course, the thieves would get to keep the finest painting in the world for themselves. The plan was brilliant because even if the forgeries were detected, the buyers would be unable to report it to the police. The original was stolen in 1911 and was missing for two years before it was discovered in the bottom of a trunk. At this time, La Gioconda, as the painting is officially called, was merely famous, rather than world-famous. The thief simply took it off the wall, and the theft was not discovered until the next day. Rumors persist that the painting that was returned to the Louvre was one of the six forgeries. No one has ever admitted to buying any of the fake Mona Lisas, and the story of the greatest art swindle has never been proven.[8] (Some even claimed that Yves Chaudron never existed!)

3 Ely Sakhai

Ely Sakhai was not himself an artist, but he employed a number of artists to create forgeries for him. He owned a high-end art gallery in New York, and it is alleged that he created forgeries for over 20 years before he was caught.[9] Sakhai purchased authentic artworks by such well-known painters as Renoir and Gaugin perfectly legitimately, at respectable auction houses. He then employed artists to make copies of the paintings before selling them with the original certificates of authenticity. It was only when Christie’s and Sotheby’s both offered the same painting by Gaugin at the same time that the scheme fell apart. One of the paintings being sold was owned by Sakhai, the other by a private seller who, ten years previously, had bought the picture from, wait for it, Ely Sakhai. Oops. It was just Sakhai’s bad luck that the other owner decided to sell at the same time that he was offloading his. Further investigations showed a whole lot more fakes sold from Sakhai’s gallery, and he was charged with eight counts of wire fraud. He is thought to have made over $3.5 million from his crimes. In 2005, Sakhai pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 3.5 years in prison and given a $12.5 million fine. He was also ordered to forfeit the 11 authentic artworks in his possession, from which his copies had been made. Hardly seems worth it.

2 John Myatt

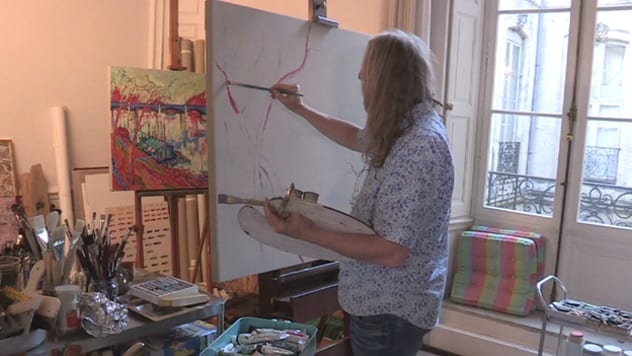

John Myatt began his career selling “genuine fakes” for £150 each. However, when one of his clients came back to him and said he had sold the painting for £25,000 and suggested that they go into business together, a new career was born. Myatt is said to have created more that 200 forgeries of famous 19th- and 20th-century painters. Myatt and his partner were convicted of conspiracy to defraud in 1999, and Myatt was sentenced to one year in prison, although he only served four months, during which time he swapped his pencil drawings for phone cards. When he left prison, he decided that his art career was over, until he was commissioned by his arresting officer to paint a family portrait, followed by requests from the prosecuting barristers. Another career as a celebrity art faker beckoned.[10] There are still an estimated 120 undiscovered Myatt fakes in circulation, but the artist refuses to disclose where they are. “I can’t see who gains,” he says. If he spoke up, the $100,000 paintings on the buyers’ walls would suddenly be worth nothing, so everyone involved appears to have agreed to live in blissful ignorance. John Myatt continues to create paintings “in the style of” Monet, van Gogh, and Vermeer, among others, and his paintings are regularly offered for sale through a gallery, though they are now clearly labeled as his own work.

1 Wolfgang Beltracchi

Wolfgang Beltracchi is probably one of the most famous art forgers ever. He was certainly one of the richest. Beltracchi forged paintings by some of the world’s most famous artists, and his work was, and probably still is, in some of the most famous galleries in the world. One of his paintings even graced the cover of Christie’s catalogue, though Christie’s didn’t know it at the time. A gifted painter, he spent years studying the work and styles of the painters who he copied. He never copied an existing painting, instead choosing to paint a picture that the artist might have painted and allowing a new work to be attributed to the master. While he painted the pictures, his wife acted as a seller, auctioning off “family pieces” and faking provenances. The couple were living in luxury, with several homes, fast cars, and even a yacht. However, the party was over when he created a Campendonk painting using titanium white paint. When the painting was analyzed, it was clear that such a pigment would not have been available at the time the painting should have been made. He and his wife were both arrested and sent to prison. Since his release, Beltracchi has resumed painting, this time signing his work with his own name.[11] When asked if he would change anything about his life, he has said, “I would never, never use titanium white.” Ward Hazell is a writer who travels, and an occasional travel writer.