Lucy Locket lost her pocket And Kitty Fisher found it. Not a penny was there in it, Only a ribbon around it. Both Lucy and Kitty were real people, back in the 18th century. Lucy Locket was a barmaid and some-time prostitute. When one of her wealthy lovers (the ‘pocket’) lost all his money, she dropped him like a hot potato, only to learn afterwards that her rival, Kitty Fisher, had taken up with him despite his poverty (‘not a penny’). The spat between the two ladies was well known at the time, as Kitty taunted Lucy for dropping her lover. Kitty claimed she had found a ribbon around him – a serious jibe at Lucy, as prostitutes at that time kept their money tied around the thigh with a ribbon. So not such a nice theme for the kiddies … luckily, the passing of time has been enough to hide the truth: that this rhyme records a spat between two courtesans!

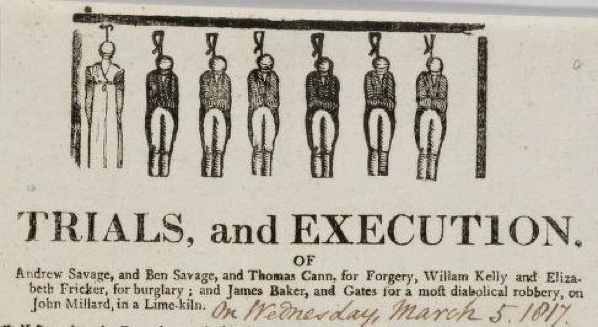

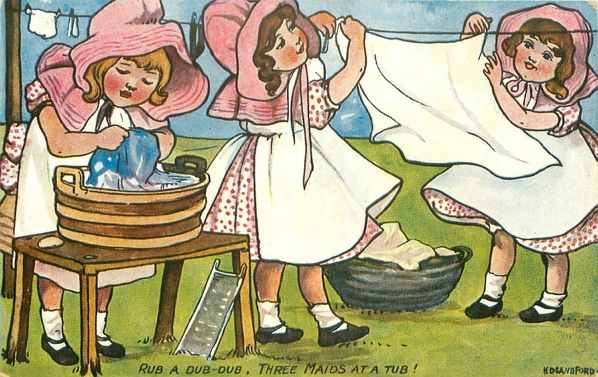

Georgie Porgy pudding and pie Kissed all the girls and made them cry When the boys came out to play Georgie Porgie ran away Georgie Porgie could be one of two men – either George Villiers (16-17th century) or Prince Regent George (late 18th century). The first was an up-start who wormed – or earned – his way into the court of King James I. George Villiers was likely a bisexual, who had an intense and fairly well-documented attachment to the king. King James was extremely fond of George, and gave him money and titles. While there is no sure, definitive proof of a homosexual relationship between the two, King James’s affection was without doubt. Either way, George still loved the ladies and was rumoured to be fond of seducing noblemen’s wives – sometimes without the consent of the ladies in question. This fact, together with well-known (and probably very necessary) ability to avoid confrontation, makes him a good fit for the nursery rhyme. As much as George Villiers may seem like the perfect candidate, my money is actually on Prince Regent George. He was enormously fat, and notoriously gluttonous. He couldn’t fit regular clothes, but he certainly fits the rhyme. He wasn’t the sharpest tool in the shed, but he definitely loved the ladies. The last couplet might refer to an incident where George attended a bare-knuckle boxing match which left one contestant dead. He ran away and hid himself, afraid of a potential scandal. So Georgie Porgie is really a coward, a cad and a glutton. Not the best moral for your children, perhaps. Oranges and lemons Say the bells of St Clemens, You owe me five farthings Say the bells of St Martins, When will you pay me? Say the bells of Old Bailey, When I grow rich Say the bells of Shoreditch, When will that be? Say the bells of Stepney, I do not know Says the great bell of Bow, Here comes a candle to light you to bed And here comes a chopper To chop off your head! Chip, chop, chip, chop The last one is dead! The second part of this rhyme is a clue to the purpose of the first part – the poor fellow ends up dead! The bells belong to famous churches in London; it’s possible that these were the churches a condemned man would pass, on his way to his execution. St Clemens, the first church, is likely that in Eastcheap. The Eastcheap docks saw the unloading of cargo from the Mediterranean – often including oranges and lemons. But not only fruit was unloaded at Eastcheap: it was also the dock at which condemned men would disembark, to begin their final journey. Half a pound of tuppenny rice Half a pound of treacle That’s the way the money goes, Pop goes the weasel. Up and down the City Road In and out of the Eagle That’s the way the money goes, Pop goes the weasel. Every night when I go out The monkey’s on the table Take a stick and knock it off, Pop goes the weasel. A penny for a ball of thread Another for a needle That’s the way the money goes, Pop goes the weasel. “Pop goes the weasel” seems at first glance to be a nonsense rhyme, one without any purpose behind it at all – but really it’s an account of poverty, pawnbroking, minimum wage, and a serious night out on the town. The ‘weasel’ in the rhyme is a winter coat, which has to be pawned – or ‘popped’ – in exchange for various things. The first verse describes the cheapest food available; the narrator of the poem has no money, so ‘pop’ goes the weasel. The second verse describes a night out at a music hall called the Eagle Tavern, which was located on the City Road. But music halls – and drinks – cost money. Pop goes the weasel. The third verse is a bit more obscure than the first two; a monkey is slang for a tankard, while knocking off a stick was slang for drinking. The last verse probably refers to the narrator’s day job. So this little nonsensical ditty is actually about struggling to make ends meet. It’s still an upbeat tune, letting the reader see that a night on the town is well worth the week of terrible food, wages and general living conditions. Rub a dub dub Three men in a tub And how do you think they got there? The butcher, the baker and the candlestick-maker It was enough to make a man stare. At first it’s a bit homoerotic… then we read the original, or at least the oldest known version: Rub a dub dub Three maids in a tub And how do you think they got there? The butcher, the baker and the candlestick-maker And all of them gone to the fair. Well, it sounds like a peep show might be in town. Peep shows were a popular form of entertainment in the 14th century, and it appears that our friends have gone to catch a glimpse of the maids in the tub. Rub a dub dub…

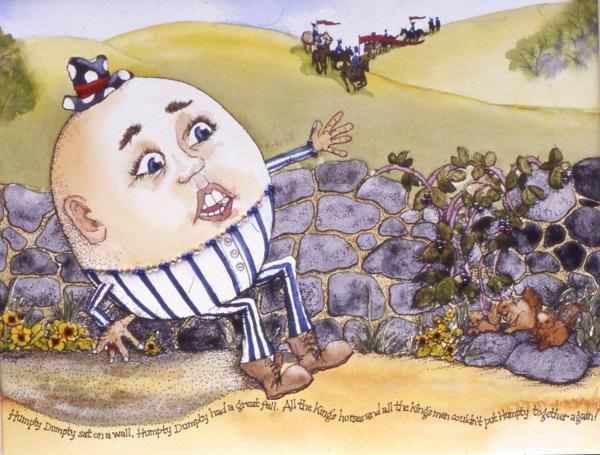

Mary, Mary, quite contrary How does your garden grow? With silver bells and cockleshells And pretty maids all in a row. This one has a bit of a sad, nostalgic ring to it – only increased when you realize that in some versions, ‘garden’ is replaced with ‘graveyard’. The Mary here is probably Mary I, daughter of Henry VIII and sister to Elizabeth I. Henry VIII was initially married to Catherine of Aragon, and the couple had one child, Mary. But Henry wanted a son – and always true to the notion of killing two birds with stone, he decided to do this by getting into the pants of Anne Boleyn, one of his wife’s ladies in waiting. To cut a long story short, Henry was refused a divorce by the Pope – so he created the Anglican Church with himself at the head, thereby isolating himself from Catholic Europe. After divorcing Catherine and marrying Anne, he had one child with the latter – Elizabeth. Needless to say, that marriage didn’t work out either. Henry had Anne executed, and went through another couple of wives in an attempt to find a son. After his death, the throne went to Mary, who promptly tried to make England Catholic again. So Mary went ‘quite contrary’ to England’s wishes – by this stage, a lot of people were happily Protestant. In the rhyme, ‘garden’ sounds a lot like Gardiner – the name of Mary’s only religious supporter. It could also be a dig at Mary’s own infertility, or if ‘garden’ is replaced by ‘graveyard’, a reference to the growing pile of dead Protestants. Given that silver bells, cockleshells and maids are also terms for torture devices of the age, it no longer seems such a pretty little rhyme. Baa baa black sheep, Have you any wool? Yes sir, yes sir, Three bags full. One for the Master, One for the Dame, And one for the little boy Who lives down the lane. And with the original ending… And none for the little boy who cries down the lane. The song is definitely not about black sheep, or even little boys – it’s about taxes! Back in the 13th century, King Edward I realized that he could make some decent cash by taxing the sheep farmers. As a result of the new taxes, one third of the price of a sack of wool went to the king, one third to the church and the last third to the farmer. Nothing was left for the shepherd boy, crying down the lane. As it happens, black sheep are also bad luck: the fleece can’t be dyed, and so it’s worth less to the sheep farmer. Baa Baa Black Sheep is a tale of misery and woe. Humpty Dumpty sat on the wall Humpty Dumpty had a great fall All the King’s horses and all the King’s men Couldn’t put Humpty together again! Humpty Dumpty wasn’t a real person; nor was he an odd, fragile egg-shaped thing. It turns out that Humpty Dumpty was a cannon. Owned by the supporters of King Charles I, Humpty Dumpty was used to gain control over the city of Colchester during the English Civil War. Once in Colchester, the cannon sat on church tower until a barrage of cannonballs destroyed the tower and sent Humpty into the marshland below. Although retrieved, the cannon was beyond repair. Humpty the cannon was a feared and effective weapon – as the full rhyme demonstrates: In sixteen hundred and forty-eight When England suffered pains of state The Roundheads laid siege to Colchester town Where the King’s men still fought for the crown. There one-eyed Thompson stood on the wall A gunner with the deadliest aim of all From St Mary’s tower the cannon he fired Humpty Dumpty was his name. Humpty Dumpty sat on the wall Humpty Dumpty had a great fall All the King’s horses and all the King’s men Couldn’t put Humpty Dumpty together again! And you though it was all about an egg? A 19th century illustration in Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass created this myth. When Alice talks to Humpty Dumpty on the wall, the illustrator – apparently at a whim – made him egg-shaped. Given the popularity of the book, a generation of kids grew up thinking that Humpty Dumpty was a nonsense rhyme about an egg, rather than a fearsome killing machine. Ladybird ladybird fly away home Your house is on fire and your children are gone, All except one called Anne For she has crept under the frying pan. This poor little ladybird is really a Catholic in 16th century Protestant England. Ladybird is a word that comes from the Catholic term for Our Lady. It was illegal for Catholics to practice their religion, and non-attendance of Protestant services meant hefty fines for absentees. Catholics were forced to say Mass and attend services in secret, often outdoors and in outbuildings. The fire may refer to the Catholic priests who were burned at the stake for their beliefs. Ring a ring a roses, A pocket full of posies A-tish-oo, a-tish-oo We all fall down This is one nursery rhyme origin we think we already know to be sinister. But it has nothing at all to do with the Black Death. The first known reference to the rhyme is in 1881, more than 500 years after the plague swept across Europe. By all accounts, it seems to be a nonsense rhyme – and in its 1881 form, there isn’t even any sneezing. Here’s a version from the mid 20th century: Ring a ring a roses, A pocket full of posies One, two, three, four, We all fall down down The sneezing was added sometime in the last 50 years or so. So this one really is just a nice little rhyme – no ulterior meanings at all!