10The Lord Chamberlain’s OfficeBritain

For nearly 200 years, all the way up until 1968, the Lord Chamberlain’s Office was the undisputed ruler of the British stage. It was originally created in the late 15th century, and the man who held the post of Lord Chamberlain was just in charge of entertainment at Court. But by the middle of the 17th century, the Office began to interfere in and censor public theaters, often for political or religious reasons. Some of the most celebrated plays of the 19th and 20th centuries were banned from Britain, for reasons ranging from bad language (even as mild a word as “piss”) to the depiction of Queen Victoria and Florence Nightingale in a lesbian relationship (Edward Bond’s Early Morning). Most plays were sent back with a list of required changes and some playwrights refused to obey, showcasing their work in private clubs, which the Office usually left alone.

9The Australian Classification BoardAustralia

An out-of-touch, outdated mode of censorship, the Australian Classification Board is responsible for investigating and classifying video games, movies, and TV shows. Established as the result of a political bill in 1995, the ACB has the power to ban any item which it feels does not represent the established morality of Australia, especially in regards to violence or sexuality. However, items are usually given a chance to make changes based on the Board’s decision to receive classification. Video games seem hardest hit with this strictness, with examples like Saints Row IV and State of Decay refused classification. (The developers later edited out parts of the games to meet the Board’s requirements.) Though the games include over-the-top violence, movies with extreme amounts of violence are often allowed right on through.

8The Motion Pictures Producers And Distributors Of AmericaUSA

In 1922, after public outcry over the perceived vulgarity in cinema, as well as real-life scandals involving film stars, studios in the United States banded together and asked former Postmaster General William Hays to head a board to come up with a set of rules to govern films. They did this more out of a desire to keep the government out of their business, rather than a moral reason. In 1930, they developed the Motion Picture Production Code, a detailed list of the things acceptable for film. Items such as extreme profanity, nudity, or white slavery were normally banned by the Code. By the 1960s, the MPPDA was extremely outdated, and it was gradually turned into the Motion Picture Associations of America. The old rules were relaxed quite a bit, and the ratings system was changed to reflect the societal changes throughout the US

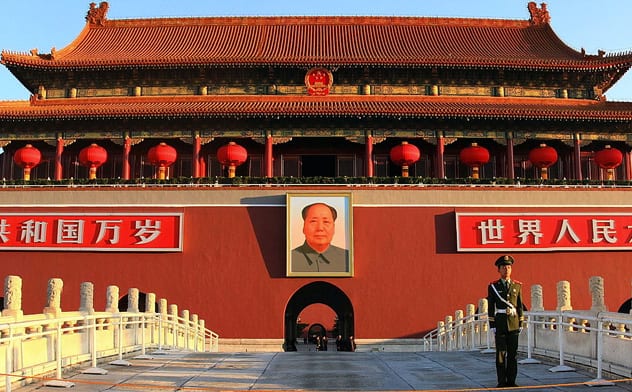

7The General Administration Of Press And PublicationChina

Established by the Communist Party of China, the General Administration of Press and Publication (GAPP) is responsible for monitoring all print, electronic, or Internet media distributed in China. Items are banned as content detrimental to the country, as well as for indecency or violence. Sometimes, regulatory overreach seems like their only goal, like in 2003, when they banned 19 dictionaries. They’re also responsible for investigating and prosecuting people or organizations who illegally publish banned materials. In addition, a few years ago, the GAPP merged with the board responsible for monitoring radio, film, and television (SARFT), which was just as restrictive with its censoring. The Internet was partly to blame for the necessity of the merger, as both censorship groups tried to exert their control over the new media.

6The Office Of CensorshipUSA

During World War II, the Office of Censorship was set up by President Franklin Roosevelt because, in his words, “Some degree of censorship is essential in wartime.” The US government didn’t want the Axis powers to have any additional information about how the war was going or how the public felt about it. However, its strictness led to some unbelievable censoring, such as when Eleanor Roosevelt was censored for writing an about the weather conditions of the area in which she and FDR were staying. (Her words on the subject were: “ . . . and so from now on I shall not tell you whether it rains or whether the Sun shines where I happen to be.”) A code was developed for news organizations, and they were encouraged to police themselves, which may have made the program easier to swallow. One of the major downsides to the Office of Censorship was when they refused to allow information about the Japanese balloon bombs to be given to the public, which may have led to deaths. The program officially ended on August 15, 1945.

5Index Librorum Prohibitorum

The Librorum Prohibitorum, or “Index of Forbidden Books,” was a Roman Catholic list of books deemed harmful to their faith or that corrupted the morals of the public. It was established by Pope Paul IV in 1559 and focused mainly on scientific work and most writings done by people who were of a different faith, especially Protestants. Roman Catholic canon law instructed them to censor writings in two ways: stop the publication if possible and condemn it if they couldn’t stop the publication. Heretical work was especially condemned by the Church. Nearly 20 different editions of the Index were created, banning works by authors like Galileo, Nietzsche, Martin Luther, and others. The final list was sent out in 1948 and the practice stopped in June 1966. (There was an informal banned list as early as 496, which was laid out by Pope Gelasius I.)

4The Publication Ordinance Of 1869Japan

Drawn up by the newly formed Meiji imperial government, the Publication Ordinance of 1869 was originally claimed to be a licensing system to protect publishers from piracy but didn’t do much for the authors themselves. Instead, it transformed into a way for the Japanese government to censor whatever it wanted, since every publication had to be preapproved by the board. People found publishing material deemed harmful to the government or to the public could be fined or even jailed, if they didn’t stop. Later laws, such as the Press Law of 1893, greatly enhanced the abilities of the government, even allowing them to shut down an entire newspaper on a whim.

3Nazi CensorshipGermany

As early as the spring of 1933, lists of “un-German” books were created. On May 10, 1933, more than 25,000 books by authors such as Einstein, Freud and Hemingway were burned in large bonfires while the Germans sang around the flames. When Helen Keller learned her books had been burned, she responded: “Tyranny cannot defeat the power of ideas.” To get around the book burnings, some Germans resorted to tarnschriften, camouflaging the illegal book as a more benign book. (One Joseph Stalin speech was labeled: “How to Keep Potatoes From Frost.”) Joseph Goebbels, in addition to being the Minister of Propaganda, was responsible for much of the censorship. Nearly every aspect of life was watched—music, news, and even private conversation. (It was considered highly illegal to even make jokes at Hitler’s expense.) In addition, schools were highly censored, creating a generation of children brought up to love the Fuhrer.

2KwangmyongNorth Korea

Kwangmyong (“bright”) is part of a larger, concerted effort by the North Korean government to stifle its citizen’s ability to interact with the outside world. Technically known as an “intranet,” the service functions as the Internet for nearly every person in North Korea. Very few people are allowed to have access to the actual Internet. Kwangmyong allows citizens a browser and email, but the unauthorized parts of the Internet are blocked off by China’s “great firewall.” In fact, an estimation in 2014 said there are only 5,500 sites accessible through the network. Many citizens are turning to black market Chinese cell phones, which can access the Internet if they are close enough to the border, but they are highly illegal and the penalties can be quite severe.

1The Padlock ActCanada

To curb what they felt was the tide of communism about to invade their province, the government of Quebec enacted the Act Respecting Communistic Propaganda in 1937. Vague in its description of what constituted communism or bolshevism, the law allowed the government to close any building suspected of trying to undermine the government for a year. (Hence the name “the Padlock Act.”) In addition, anyone found printing or distributing materials that promoted communism or bolshevism could be sentenced to a year in prison and were unable to appeal the decision. It wasn’t until 1957 that the Canadian Supreme Court struck the law down, stating it was unconstitutional.