During this reign of terror, the various secret police organizations of the USSR are believed to have killed tens of millions of Soviet citizens. Under the reign of Joseph Stalin alone, the closest thing to an academic consensus is that 2.9 million people died in the dreadful work camps (known as gulags) or during forced peasant resettlements. Others argue that Stalin’s reign was far bloodier than this, and there is ample evidence to back up this supposition. However, many people know about Stalin’s crimes. Fewer people know about the crimes committed by the Soviet secret police. Tragically, many of the men who headed the various Soviet agencies were just as bloodthirsty and tyrannical as Lenin or Stalin. The following list hopes to provide a look at just how demonic these men and their actions truly were.

10 Yakov Peters Was A Bank Robber And A Murderer

The name Yakov Peters is not well-known. Peters was an ethnic Latvian who grew up in the hardscrabble world of rural Latvia during the days of the Russian Empire. At that time, Moscow officially ruled Latvia (then called Courland and Livonia), but Baltic Germans truly dominated. Men like Peters’s father worked for low wages on massive plantations run by ethnic Germans who enjoyed social and economic privileges. When he became a young adult, Peters joined the Latvian Social Democratic Workers’ Party, a revolutionary political party based in the city of Riga. After taking part in the Russian Revolution of 1905, Peters migrated to London where he joined fellow Latvian Communists. In late 1910, Peters and other political radicals, including an infamous bandit nicknamed “Peter the Painter,” began robbing several stores and even a train in the London area of Houndsditch. These crimes also included the murder of two police officers, both of which author Donald Rumbelow has blamed on Peters. The crimes committed by the Latvian terrorists came to a head in January 1911 when London police officers and riflemen with the British Army laid siege to a Sidney Street apartment belonging to “Peter the Painter” and his accomplices. The two sides exchanged gunfire for hours, and the battle did not end until that afternoon.[1] One police officer died months later of injuries sustained during the siege, while two of the radicals died outright. Peters escaped London relatively unscathed. He returned to Latvia and then went to Russia proper during the 1917 revolution. Once the Soviets took power, Peters was named as the first Deputy Chief of Soviet State Security (aka the Cheka). In this capacity, Peters oversaw several bloody purges against anti-Bolshevik forces in the Caucasus region, including the battles against the pan-Turkic and pan-Islamic Basmachi movement.

9 The Polish Operation

The history between Poland and Russia is a bloody one. This gore reached its apex in the 20th century, especially during World War II. Between 1939 and 1941, during the time when the USSR had a nonaggression pact with Nazi Germany, the Soviet Red Army bulldozed through half of Poland. The most infamous example of anti-Polish operations conducted by the Soviets was the Katyn Massacre of 1940, which killed approximately 22,000 members of the Polish Army officer corps.[2] Prior to this, the NKVD, the secret police organization used by Stalin during his murderous reign, carried out what it called its “Polish Operation.” This operation lasted from 1937 until 1938. This action was part of the larger “Great Purge,” which saw the mass execution of at least one million suspected “dissidents” within the Soviet Union. The “Polish Operation” was officially sanctioned by NKVD Order No. 00485. This letter from the People’s Commissar of Internal Affairs authorized the NKVD to eliminate “Polish spies.” This directive was liberally applied, and almost all ethnic Poles within the Soviet Union were targeted for execution or imprisonment. During the year-long operation, Polish citizens, Polish socialists, Polish Communists, and even prisoners of war from the Polish-Soviet War of 1919–1921 were executed. The death toll is believed to be in excess of 111,000 people. A further 28,000-plus Poles were sent to gulags in Siberia, where thousands died due to malnutrition, exposure, and disease. Michal Jasinski, a Polish historian, has also written that the NKVD mostly killed Polish men with families, while their wives, sisters, and other Polish women were deported to Kazakhstan.

8 The Vinnytsia Massacre

Ethnic Poles were not the only group who felt the wrath of the Soviet state. Ethnic Ukrainians were frequently targeted for mass deportations and mass violence as well. The citizens of one Ukrainian town, Vinnytsia, were virtually wiped out between the bloody years of 1937 and 1938. When the extent of the massacre first came to light in 1943, a total of 9,439 bodies were found, with most indicating that a .22-caliber gun had been used to kill them execution-style. Of these corpses, 169 were identified as women. Most of the victims had previously been sentenced to various prison camps in Ukraine. Most people quickly realized that since the camps were run by the NKVD, then it was likely that the victims had been killed by the NKVD. The Vinnystia Massacre, like Katyn, proved to be very controversial because it was the German Army that first reported finding mass graves. For the Soviets, this fact proved to be a propaganda coup because Moscow could simply say that the Nazis were blaming the Soviets for a crime that they had committed themselves. However, historians today almost unanimously agree that the NKVD was responsible for murdering the citizens of Vinnystia.[3]

7 The Massacre Of Jeltoqsan

The most well-known secret police organization of the Soviet state is the KGB. It was first formed in 1954, a year after Stalin’s death. The KGB was intended to erase the stain of the NKVD, which the post-Stalin leaders of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union blamed for several excesses. However, the KGB soon became known for committing plenty of atrocities all on its own. In December 1986, the KGB and the OMON (the Special Purpose Police Unit) were ordered to Kazakhstan to put down a nascent anti-Soviet protest movement. The true origin of the conflict began when Moscow replaced former Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic leader Dinmuhammaet Kunaev with Gennady Kolbin. Kolbin was an ethnic Russian with no connections to Kazakhstan or her people. The fact that Kunaev had been removed as part of an anti-corruption probe mattered very little. Thousands of people took to the streets of Almaty to protest the decision. As the protests happened in December, the incident is remembered as “Jeltoqsan” (the Kazakh word for “December”). To stop the protests from spreading, the KGB and OMON used violence to disperse the crowd. Hundreds were also arrested in an attempt to quell the revolt. All told, some 250 ethnic Kazakhs were executed during the operation while another 1,000 were sent to prison camps.[4]

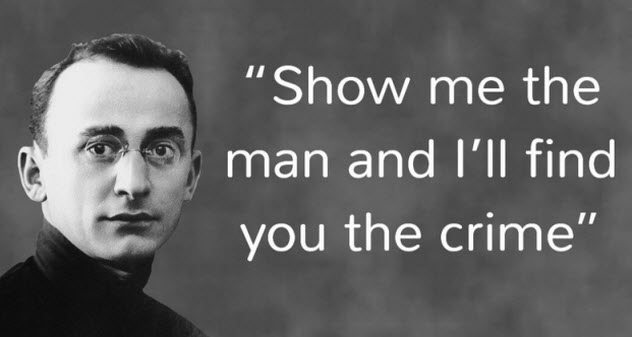

6 ‘Iron Felix’

Few people are as reviled in the annals of Soviet history as Felix Dzerzhinsky. Like a lot of the top Soviet officials, Dzerzhinsky was not an ethnic Russian. Instead, he was the scion of a noble Polish-Belarusian family and had once considered becoming a Catholic priest. However, this dream ended when Dzerzhinsky pledged his loyalty to Marxism while a college student in Saint Petersburg. Following the Russian Revolution of 1917, Dzerzhinsky was named as the first head of the Cheka, the dreaded secret police force that served under Vladimir Lenin. The spark that ignited “Iron Felix” to commit mass terror occurred on August 30, 1918. On that date, Fanny Kaplan, a member of the recently outlawed Socialist Revolutionary Party, tried to assassinate Lenin as he left a Moscow factory. When Kaplan refused to name her accomplices, the Cheka executed her on September 3, 1918. Subsequently, Dzerzhinsky began to argue in print about the necessity of using terror to suppress Soviet dissidents within the country. In the pages of Novaia Zhizn, Dzerzhinsky wrote that the Cheka stands “for organized terror.” He urged Soviet citizens to spy on each other and inform the Cheka about possible counterrevolutionary activity whenever possible. Dzerzhinsky made it clear that the purpose of spying was to help the Cheka kill as many counterrevolutionaries as possible.[5] Under Dzerzhinsky, a “Red Terror” campaign was orchestrated that killed at least 800 people without trial. His Cheka also executed thousands of White Russian soldiers, especially those who were captured by the Soviet Red Army during the Russian Civil War. It can be said with certainty that “Iron Felix” created the blueprint for the Soviet terror state.

5 The Aardakh

Many would argue that the roots of the Russian-Chechen conflict can be traced all the way back to the 19th century. Another source of the conflict is the “Aardakh,” or forced migration of Chechen and Ingush Muslims during the 1940s. Despite fighting the deadliest war in human history, the Soviet state still found the time and energy to forcibly deport half a million Chechen and Ingush citizens from their homes. This operation was overseen by the NKVD, and it was justified as a punishment for the supposed support that Caucasian Muslims gave to the Nazis. While it is certainly true that many ethnic minorities in the Soviet Union—including Ukrainians, Latvians, Estonians, and Caucasian Muslims—provided troops for the Waffen-SS, the Soviets used this as a justification to physically deport one-third of the entire Chechen and Ingush populations to Central Asia. The best Soviet records indicate that 407,690 Chechens and 92,074 Ingush were sent to Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan in February 1944 alone. Like other ethnic minorities, including the Volga Germans and Crimean Tatars, the Chechens and Ingush were not allowed to return to their ancestral homelands until the 1980s.[6] It is unknown how many people perished on the journey to Central Asia. Historian Nikolay Bugay says that over 100,000 died while being transported to Kazakhstan and another 16,000 died from starvation and disease while en route to Uzbekistan. Another source says that as many as 200,000 may have died in prison camps.

4 ‘Iron Lazar’

Lazar Kaganovich was one of the great executioners of the Stalinist era. He was born into a Jewish family in Ukraine in 1893. As a young man, he eagerly joined the Bolsheviks at a time when they were officially outlawed by the tsarist authorities. Kaganovich’s first taste of power came when he was a propaganda commissar during the Russian Civil War. However, his bloodlust would not reach its zenith until the many massacres orchestrated by Stalin during the 1930s. According to one popular saying, Kaganovich “out-Stalined” Stalin.[7] As the First Secretary of the Communist Party of Ukraine, Kaganovich organized the forced collectivization of farms that killed thousands between 1925 and 1929. Then, between 1935 and 1939, he held several commissar positions in the transportation, heavy industry, and fuel industries. In this capacity, Kaganovich used forced labor to quickly industrialize the Soviet economy. Hundreds of thousands of workers died during their projects, and many more were sent to the gulags or outright executed as “saboteurs.” Kaganovich managed to survive the post-Stalin Soviet Union and died at age 97 in 1991.

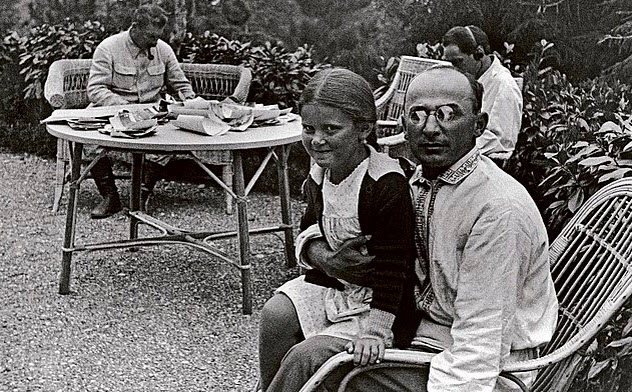

3 The Political Massacres Of Lavrentiy Beria

Lavrentiy Beria, the head of the NKVD during the 1930s and 1940s, was a man so awful that he committed crimes as a public official and in his private life. Again, like so many of the arch butchers of the Soviet period, Beria came from the Russian periphery and was not part of the ethnic majority. Of Georgian Orthodox extraction, Beria came from the same milieu as his future boss, the ethnic Georgian Joseph Stalin. Much like Kaganovich, Beria thrived during the Stalinist period because of his ruthlessness and his ability to please Stalin as one of his chief executioners. During his 15-year reign as the top cop in the NKVD, Beria was responsible for the execution of millions of Russians, including an untold number who were executed in the infamous Lubyanka prison. Under his watch, the NKVD carried out massacres in Poland and Ukraine, including the Katyn Massacre. Beria’s awfulness was legendary, with even other members of Stalin’s inner circle calling him “the bloodthirsty dwarf.” He more than lived up to this nickname, especially during World War II when his NKVD agents sent many Russian citizens to the gulags or worked them to death in factories to make sure that the Soviets would win the day against the Germans.[8]

2 Lavrentiy Beria—Sexual Predator

Besides orchestrating several mass executions, Lavrentiy Beria was also a noted rapist and sexual predator who used his powerful position to assault an untold number of women and girls. During his trial in the 1950s, many NKVD officers came forward to testify that Beria regularly used his Packard limousine to snatch up young women in Moscow. These same testimonies claimed that Beria would feed his captives wine and food before raping them in his soundproof office. A later inspection of Beria’s office in Moscow revealed that the NKVD official kept female underwear, sex toys, pornographic pictures, and torture implements in his office desk. Even famous actresses and breastfeeding mothers were not safe from his sexual depravity.[9] For these crimes and many others, Beria was put on trial by the Soviet authorities in 1953. He was eventually found guilty of several offenses, including treason (Beria was accused of maintaining relations with foreign intelligence services), anti-Soviet activity (he briefly worked for the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic, a breakaway democracy that lasted from 1918 until 1920), and terrorism for the great purge of the Red Army in 1941 that killed several generals and displaced many others after the Soviet army performed poorly in Finland. It is telling that not a single individual came to Beria’s defense during his trial.

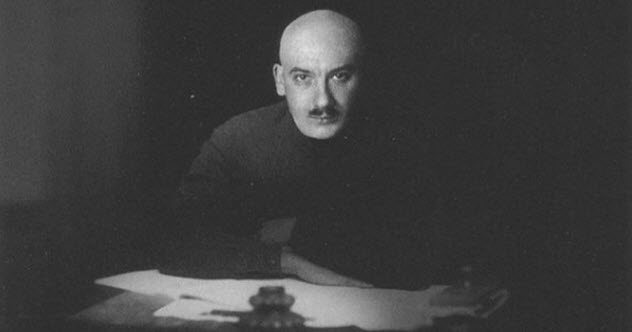

1 Genrikh Yagoda

Genrikh Grigoryevich Yagoda was the top man at the NKVD from 1934 to 1936. The son of a Jewish jeweler in a medium-sized Russian city, Yagoda became an atheist while a young man and joined the Bolsheviks in 1907. Between 1920 and 1934, Yagoda worked for the Soviet secret police as a director of the gulags. These forced labor camps killed untold millions of Soviet citizens, most of whom died either because of exhaustion, dehydration, disease, or starvation. None of this hurt Yagoda’s career prospects, and in 1934, he was named as the head of the newly created NKVD. In 1937, Yagoda dramatically fell from grace. During that time, the Great Purges began and anyone suspected of supporting Leon Trotsky rather than Joseph Stalin was put on trial and executed soon thereafter. That is exactly what happened to Yagoda, who was executed on March 15, 1938. During his short stint as an important Soviet official, Yagoda not only played a role in the first purge of the Red Army (a supposedly anti-Nazi purge that saw 30,000 officers arrested and thousands executed), but he and Kaganovich also played integral roles in creating the forced famine in Ukraine that is best known as the “Holodomor.”[10] Between 1932 and 1933, Stalin’s efforts to collectivize Soviet farms dovetailed with his desire to obliterate nascent Ukrainian nationalism. As a result, grain, including seed grain, was confiscated from semi-independent Ukrainian and Central Asian peasants. Many people were executed at this time for merely possessing grain. It is believed that somewhere between six and seven million Ukrainians perished during this famine. The Holodomor remains a controversial topic, with many Russians refusing to even acknowledge its existence. Although it is recognized as a genocide by many nations, that is not the case in the United States. This may be due in part to the fact that the once-respected journalist Walter Duranty of The New York Times deliberately covered it all up to please Soviet officials. Benjamin Welton is a freelance writer based in Boston. Read More: Twitter Facebook The Trebuchet