Not this time. Many of the best finds—the history changers and mystery makers—came from places that have been excavated for years. Pyramids bearing palaces, identical towns, and recycled monuments are just a few of the finds that recently came to light.

10 A Hidden Passage

The city of Teotihuacan is a historical gem. Located in Mexico, this pyramid-filled metropolis once saw around 125,000 inhabitants. During ancient times, Teotihuacan also ranked among the busiest places that received visitors. Today, it keeps researchers occupied with stunning architecture and a few mysteries. (For example, nobody knows why the population disappeared.) Recently, scanning technology was used to “excavate” unreachable places. A peek inside the so-called Pyramid of the Moon, which was constructed around the third century AD, detected a hidden passage. The corridor was not alone. There was also a chamber, measuring around 15 meters (50 ft) wide. This cavity was 8 meters (26 ft) underground. The tunnel also linked the room to a large plaza. Previously, other non-temple corridors at Teotihuacan yielded human remains within a funeral-type setting. If the structures inside the Pyramid of the Moon contain burials, they could explain one purpose of the pyramids. Researchers suspect that “tunnel graves” inside the monuments could represent a kind of journey to the underworld.[1]

9 Origins Of Chocolate

In 2002, the discovery of an unknown people caused a sensation. Called the Mayo Chinchipe culture, they once lived in the highlands of Ecuador. In 2018, artifacts were removed from a site called Santa Ana (La Florida). Scientists wanted to test for the key ingredient of chocolate—seeds from the cacao tree. The results changed the history of chocolate. For one, the popular assumption that it originated with the Maya and other Mesoamericans was turned on its head. Over 40 stone and ceramic items showed traces of theobromine, the concentrated signature of cacao seeds. This proved that chocolate was first used by the Mayo Chinchipe culture over 5,000 years ago. It moved the origins of the popular treat back almost 1,500 years as well as out of Central America and into South America. Analysis showed that, besides adopting the hot drink, the Maya also learned how to grind the seeds from the Mayo Chinchipe.

8 A Secondhand Monument

In 2018, archaeologists and volunteers gathered on a farm near Beaulieu in England. They investigated what appeared to be a Bronze Age barrow (grave). Despite no evidence of a burial mound or funeral activity, the 3,000-year-old barrow did not disappoint. Inside were four urns, each containing a human cremation. They were found in an unexpected position. The team first identified what they believed to be a mere ditch circling the barrow, but this ring contained the urns. The vessels, which were domestic pots, were also placed upside down inside small pits. Archaeological digs in this region are rare enough, but to find an intact burial was even more exciting. A unique twist came to light when the shovels dug deeper. A pair of flint tools, one of them a spearhead, was recovered and determined to be around 5,000 years old.[3] A scan also revealed the possibility of two entrances that belonged to a now-missing Neolithic monument. This building was later found by a Bronze Age community and recycled as a memorial.

7 Temple Under A Pyramid

In September 2017, an earthquake rocked Mexico. The 7.1-magnitude event was devastating. Among the places affected was the archaeological site of Teopanzolco. Archaeologists were shaken to find that the settlement had been badly damaged. One pyramid suffered serious reshuffling. A scan attempted to determine the level of damage inside, and to everyone’s surprise, several walls showed up. They had nothing to do with the pyramid. In fact, they were much older and belonged to a separate temple. The main parts of Teopanzolco were constructed during the 13th century, but the walls date back to at least AD 1150. The temple was the work of the Aztec people, in particular, the Tlahuica culture.[4] During its heyday, the building would have measured 6 meters (20 ft) by 4 meters (13 ft) as a sacred building dedicated to the rain god, Tlaloc. Few artifacts remained inside, but pottery bits and an incense burner were recovered.

6 Corridor Full Of Idols

Chan Chan was the capital of the Chimu Kingdom (AD 900–1430) in Peru. The city was awarded World Heritage status in 1986, and archaeologists have puttered about ever since. After decades of this, the discovery of large artifacts inside an unknown corridor was a surprise. In 2018, wall renovations fixed a section called the Utzh An complex. At some point, somebody stumbled upon a new passageway. It measured 33 meters (108 ft) long and likely served a ceremonial purpose. Images decorated the walls, showing motifs that resembled waves, landscapes, and feline creatures. However, what stunned those who first entered the passageway were the idols. Recessed into the walls were 19 rectangular windows, each holding a figurine. The 19 wooden statues, shaped like humans, were carved with unique features. Standing 70 centimeters (28 in) tall, some gripped scepters and carried shield-like objects. Clay masks also covered some of the idols’ faces. The collection is not the first of Chan Chan idols. But at 750 years old, they are the most ancient.[5]

5 Unexpected Segregation

In the distant past, Alpine villages stood on stilts. Many eventually collapsed into moist soil, preserving artifacts that wouldn’t normally survive. Things like textiles and wood, rarities in the archaeological record, have been recovered from stilt sites in Switzerland. In 2010, construction workers prepared an area near the shores of Lake Zurich for a parking garage. Told to expect “a few archaeological finds,” they instead discovered a village as big as two football fields. The 5,000-year-old settlement sparked the largest local excavation effort in 30 years. Among the thousands of artifacts was one of the oldest doors in Europe. In 2018, a new report revealed an unexpected aspect about the Neolithic occupants. They practiced blatant social segregation. It appeared that the affluent did not want to live among those who were less fortunate. Separated by a wooden fence, one side held all the biggest homes and the other did not yield a single high-status artifact. This was something nobody truly expected to find at a fourth millennium BC site.[6]

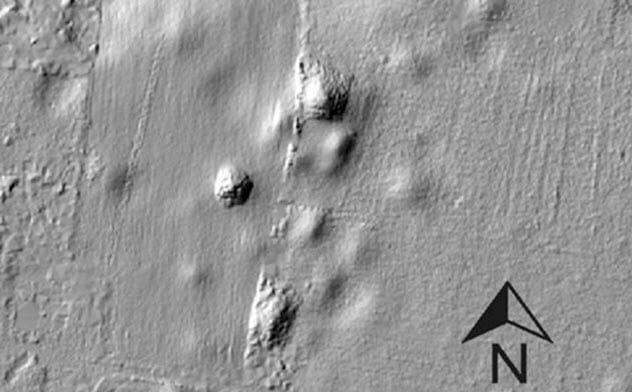

4 Copycat Towns

In 2018, archaeologists conducted surveys in Mexico. The object of their affection was a city called Izapa, the capital of the Izapa kingdom (700–100 BC). Since the 1940s, the site has churned out pyramids, ball courts, plazas, and monuments carved with exquisite details. The surveys aimed to learn more about what surrounded the capital. Incredibly, the scans found that Izapa was far from alone. About 40 towns in various sizes encircled the famous ruins. They covered an area of 584 square kilometers (225 mi2) and shared an intriguing trait.[7] Each settlement’s layout was identical to Izapa’s. This required immense dedication and coordination from the kingdom’s people, an astounding feat in itself. Most towns had a pyramid on a platform in the northern section (believed to be a ceremonial stage). The south held plazas and mounds, raised just enough to give a person a good view of the stage. Three lower-order sites also had ball courts in the south as well as mounds resembling known Mayan observatories. The important structures showed that even the smaller towns were tied to the capital and expected to perform specific ritual activities.

3 Thousands Of Ruins

The heat wave of 2018 ruined crops and summertime for many in the United Kingdom. However, the event was an archaeological bonanza. The scorching temperatures removed a lot of vegetation and revealed landscapes littered with hidden lines. Mostly foundations, the original structures were long gone. The geometric shapes showed the ancient presence of what was once burial mounds, farms, and monuments. Field borders, villages, and military camps were also found. Aerial surveys logged over 1,500 new sites, including rare structures. In Yorkshire, square barrows from the Iron Age could contain spectacular grave goods. (Past barrows held chariots.) Cornwall produced an unusual prehistoric village. Concentric ditches from prehistory as well as Iron Age foundations suggested that the site was inhabited continuously for 4,000 years. A new henge turned up in Ireland and a rare medieval graveyard in Wales.[8] The oldest finds were two Neolithic cursus monuments raised between 5,600 and 5,000 years ago. Measuring several miles long, the corridor-like structures were found near Milton Keynes, Britain’s famous collection of ancient field monuments.

2 Pyramid Of Shimao

Years ago, a city was discovered in China. No trace of its name survived, but the ruins are known as Shimao. At first, archaeologists thought it was a part of the Great Wall, but recent work proved it was older. The wall’s construction started 2,700 years ago while the city was 4,300 years old. Recent excavations at Shimao unearthed gory and spectacular new features. Near one gate, pits contained the skulls of sacrificial victims. For 500 years, the city also bustled around a pyramid. The latter was majestic, measuring 70 meters (230 ft) high and 59 acres at its base. Images of eyes and animallike human faces decorated the pyramid, both thought to be talismanic art to give the monument power.[9] The top level (there were 11) was a wonderland. The surface supported a small city of its own, including palaces and a massive water reservoir. This was the place from which the elite ruled the 988-acre settlement. The pyramid served as a production site for art and industrial processes. In addition, sophisticated walls guarded the entrance to protect and restrict access to the upper levels.

1 Electromagnetic Giza Pyramid

The Great Pyramid of Giza is more than just a popular tourist attraction. The monument is an engineering feat with properties not fully understood. In 2018, the pyramid revealed another astounding possibility—the ability to focus electromagnetic energy. This wavelike energy is found in sunlight or household appliances like radios and Wi-Fi. Researchers were curious about whether the waves would have any effect on the Great Pyramid. The study used a mix of a smaller-scale model of the pyramid, theoretical physics, and analysis. The results showed how the limestone behemoth gathered electromagnetic energy underneath its base and inside the chambers. Researchers believe that the Egyptian engineers had no idea the pyramid’s design could pool electromagnetic waves. The work that produced the remarkable results is entirely theoretical and yet to be reproduced in real life. However, if successful, this kind of energy concentration could advance nanotechnology.[10] Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages