10 Jules Goux

On May 30, 1913, French racer Jules Goux became the first European to win the Indianapolis 500. The following year, the race organizers instituted a ban on drinking alcohol while driving. That’s because Goux, according to racing legend, drank six bottles of champagne on his way to victory. The story changed over the years, and the version best remembered says that Goux had a bottle of champagne at each pit stop. However, modern historians believe that figure to be exaggerated. They claim Goux “only” had four or five bottles of champagne or chilled wine which he politely shared with his riding mechanic, Emil Begin. Either way, Goux definitely drank more than advisable while racing one of the fastest cars of the time. Jules Goux won by 13 minutes and afterward said, “Without the good wine, I would not have won.”

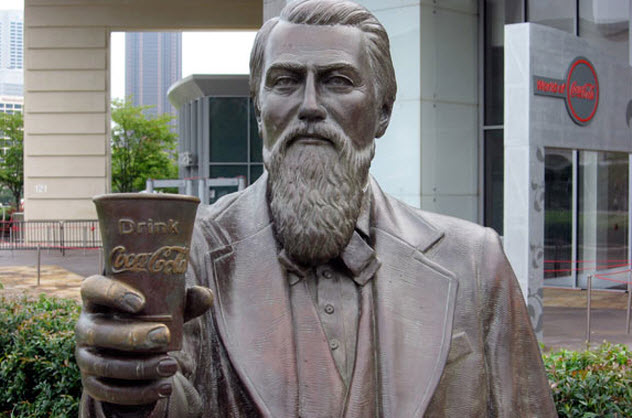

9 John Pemberton

Before John Pemberton invented Coca-Cola, he fought in the US Civil War as a Confederate soldier. He developed a morphine habit during the war to cope with his various injuries and struggled with it for the rest of his life. Pemberton used his pharmacological experience to develop a tonic that might cure his addiction. The result was Pemberton’s French Wine Coca. It was an alcoholic drink that mixed wine with cocaine and kola nuts, primarily based on an earlier Parisian concoction named Vin Mariani. As was common at the time, Pemberton promoted his drink as a panacea that could cure a wide range of ailments. However, the temperance movement forced him to develop a nonalcoholic version. Pemberton took out the wine (but kept the cocaine) and created his first batch of Coca-Cola in 1886. He never overcame his morphine addiction, though, and his financial troubles soon forced him to sell his formula.

8 Sons Of Liberty

When the Sons of Liberty dressed up as Native Americans and threw tea into Boston Harbor in 1773, they contributed to one of the most important chapters of US history. Prior to the event, some of the participants gathered at the house of journalist Benjamin Edes to discuss their next actions. Key to that meeting was a bowl filled with strong punch which sustained the conspirators as they formulated their plans. That bowl is now in the possession of the Massachusetts Historical Society, as well as correspondence from Benjamin Edes’s son, Peter. He recalls that his duty on that day was to make more punch and keep the bowl filled at all times. He had to do this several times throughout the afternoon. During the actual Boston Tea Party, several participants had to stop as they fell ill from too much rum.

7 Alexandre Dumas

Between 1844 and 1849, Alexandre Dumas was part of the Hashish Club—an exclusive Parisian group whose members enjoyed indulging in various drugs, particularly hashish. Hashish had only recently been introduced to France after Napoleon’s campaign in Egypt. Dr. Jacques-Joseph Moreau pioneered the recreational use of the drug and was soon joined by many prominent Parisian intellectuals including Victor Hugo, Charles Baudelaire, and Alexandre Dumas. Many club members wrote about their experiences with hashish, but it was Dumas who was arguably the most productive during that time. He wrote his best-known novels between 1844 and 1846—The Count of Monte Cristo and The Three Musketeers. The former even contains a memorable scene where Baron Franz d’Epinay smokes hashish with the main character, who assumed the guise of Sinbad the Sailor.

6 Paul Erdos

Paul Erdos was one of the greatest mathematicians of the 20th century, authoring hundreds of papers on a wide array of subjects. He also had a 25-year amphetamine habit. Erdos developed a reputation in the mathematical world of being an aloof wanderer. He kept most of his possessions in a suitcase, traveling from conference to conference all over the world. He’d stay at other mathematicians’ homes, where other people tended to his basic needs while he focused solely on the numbers. A bet from 1979 with his friend and fellow mathematician Ronald Graham illustrated how essential amphetamines had become to Erdos’s thought process. Worried about his friend’s health, Graham bet Erdos $500 that he couldn’t give up amphetamines for a month. Erdos accepted and won the bet. But afterward, he complained that he’d had no ideas during that time and immediately resumed taking the drug.

5 Doug Ingle

In 1968, Iron Butterfly released In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida. It became one of the best-selling albums of all time and the first album awarded a platinum certification by the Recording Industry Association of America. Most of that success is due to the album’s eponymous 17-minute psychedelic epic which was written and named by lead vocalist Doug Ingle in a drunken stupor. At the time, Iron Butterfly was technically disbanded as three members had just left the band. Remaining members Ron Bushy and Doug Ingle shared an apartment, living off Bushy’s pizza delivery job. One day, Bushy came home to find Ingle completely wasted after drinking 4 liters (1 gal) of wine. Ingle tried to show Bushy the new song he’d written, but Ingle was slurring his words so badly that Bushy wrote down phonetically what Ingle was trying to say. That’s how “in the garden of Eden” became “in-a-gadda-da-vida” and rock history was made.

4 Douglas Adams

In 1978, English author Douglas Adams developed a radio comedy series entitled The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. It went on to spawn one of the biggest franchises ever, consisting primarily of a five-book series written by Adams which sold over 15 million copies. According to Adams, he got the idea for The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy in 1971 when he was an 18-year-old traveling through Europe. One night in Innsbruck, Austria, Adams got drunk and wandered in a field. He sat down, gazed at the star-filled sky while clutching a hitchhiker’s guide for Europe, and thought that someone should write one for the whole galaxy. Afterward, he fell asleep, nearly forgetting his drunken revelation.

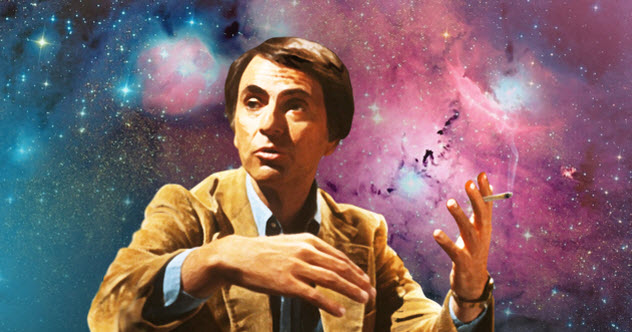

3 Carl Sagan

At the time of his death, Carl Sagan was one of the best-known scientists on the planet. Today, he is remembered not only as one of the foremost popularizers of science but also one of the most ardent advocates of marijuana. Sagan was an avid smoker for most of his adult life but kept it a secret from the general public. His friends and family knew that marijuana helped him work, and several papers were directly inspired by his cannabis use. Although Sagan kept his passion private, he couldn’t refrain from contributing an essay on marijuana for a 1971 book written by his friend and fellow smoker, Dr. Lester Grinspoon. The book was titled Marihuana Reconsidered, and Sagan published under the pseudonym Mr. X but left hints regarding his identity. In the essay, the author shares many happy experiences with the drug and credits marijuana for helping him appreciate food, music, and art better as well as improving his academic work.

2 William S. Burroughs

In 1959, Beat Generation figure William S. Burroughs published one of the most successful, most controversial novels of the 20th century—Naked Lunch. It divided critics and was banned in several places in the United States and Europe on obscenity charges. The book follows the disjointed exploits of junkie William Lee who was a thinly veiled alter ego for the author. At the time, Burroughs was a heavy drug user who had to move from place to place to evade the authorities. They were looking for him for various crimes brought on by his drug use. Most notably, in 1951 in Mexico City, Burroughs shot his wife, Joan Vollmer, in the head after a drug-fueled attempt to play “William Tell.” When he wrote Naked Lunch, Burroughs was in Tangier, Morocco. He found it hard to obtain his usual supply of heroin, so he turned to eukodal, an opioid better known today as oxycodone.

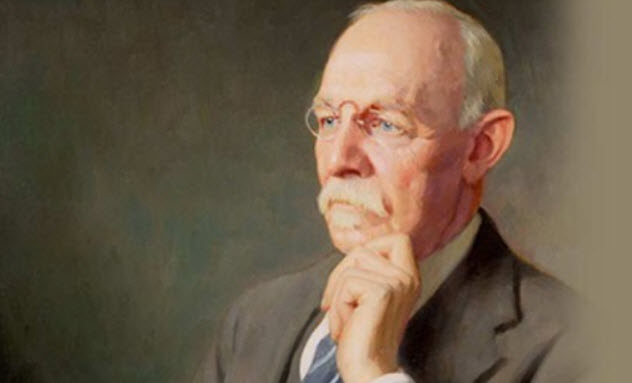

1 William Halsted

William Halsted, one of America’s most renowned surgeons, championed anesthesia and the importance of cleanliness in hospitals. He also spent most of his career dealing with a severe cocaine and morphine addiction. Halsted started his medical career in New York. Back then, the addictive properties of cocaine weren’t fully understood and it was considered one of the most effective anesthetics in the world. Halsted decided to test it on himself and soon developed a habit. As Halsted succumbed to his addiction, he lost his position in New York. Afterward, he went to an up-and-coming hospital in Baltimore named Johns Hopkins. By this time, Halsted had tried to treat his cocaine habit with morphine, failed, and developed another addiction. However, Halsted became the definition of a functioning addict. In the operating room, his work was impeccable. Between surgeries, though, Halsted was erratic, bipolar, and prone to disappearing.

![]()