The most famous of these units were the 100th Infantry Battalion and the 442nd Combat Regiment, which fought with distinction and remarkable heroism in Europe. They were two of the most decorated units in the war.

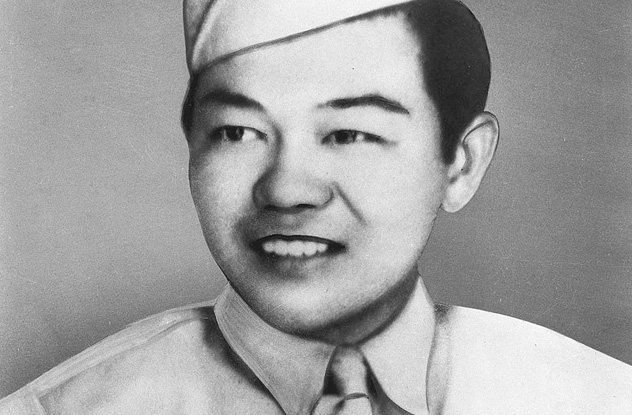

10Shizuya Hayashi’s Insane Charge

Shizuya Hayashi was drafted into the army in March 1941. He was nicknamed “Cesar” because the sergeant couldn’t pronounce his name. The day after his 26th birthday, November 29, 1943, Hayashi found himself on patrol in mountainous country near Cerasuolo, Italy. From the heights, the camouflaged Germans opened up with 88-mm cannons, taking out many US troops. Hayashi rose up amid the hail of grenade, rifle, and machine gun fire and charged a German machine gun nest. Firing his Browning automatic rifle from the hip, he cleaned out the nest, killing seven and dropping two more as they fled. Hayashi’s platoon caught up with him and advanced another 200 meters (600 ft). Hayashi faced a counterattack and killed nine more Germans and took four prisoners. A terrified teenage German soldier held up his gun, but Hayashi just couldn’t make himself shoot the crying kid. He told him to get up and took him prisoner. One of his captives had an Iron Cross, and Hayashi took it as a souvenir. Miraculously, Hayashi emerged from it all unscathed, though a sniper’s bullet had grazed his neck. Looking back, the elderly Hayashi acknowledged how insane his charge was. “I was just standing up and shooting,” he recalled. “Things happened so fast that now it seems so crazy.” For his extraordinary heroism, Hayashi received the Distinguished Service Cross, which was later upgraded to a Medal of Honor.

9Mikio Hasemoto And Allan Ohata: The Two-Man Army

In another part of the Cerasuolo battlefield, the Nisei of the A, B, and C Companies were on the approaches to Monte Pantano where German guns raining death on the troops below had to be neutralized. Inching forward through intense fire, a squad that included Sgt. Allan Ohata and Pvt. Mikio Hasemoto was protecting its platoon’s left flank when it was attacked by about 40 Germans. Though outnumbered and outgunned, Ohata braved the machine guns and advanced 15 meters (50 ft), while Hasemoto emptied four magazine clips at the enemy before his Browning was hit by gunfire. Hasemoto ran 10 meters (30 ft) back to find himself another weapon. Picking up an automatic rifle, he fired continuously until it jammed. By this time, Ohata and Hasemoto had cut the attacking force down to half. Weaponless a second time, Hasemoto again ran the gauntlet of bullets until he found an M-1. Using that, he and Ohata finally reduced the Germans to three men. In a final charge, the duo killed one, wounded another, and captured the last. But it wasn’t over yet. There was a second wave of attack, then a third. Ohata and Hasemoto fought side by side, holding their position until the next day, when an artillery shell finally killed Pvt. Hasemoto. In total, he and Ohata had killed 51 Germans and captured three. Allan Ohata survived the war but never talked about his experiences to his family. They didn’t even know of his Distinguished Service Cross decoration, and friends weren’t even aware he was in the war. Ohata died of colon cancer in 1977.

8The Agony Of Monte Cassino

The venerable abbey founded by St. Benedict of Nursia in 529 stood sentinel-like atop the 5,500-meter-high (1,700 ft) peak of Monte Cassino. Destroyed and rebuilt numerous times in its history, it was fortified by the Germans in early 1944 to block the American advance on Rome. But the home of the Benedictine Order was such a historical treasure the Allies were reluctant to bomb it. Monte Cassino had to be taken by infantry assault. It would be the fiercest and toughest battle of the Italian Campaign. Two full US regiments were annihilated just trying to cross the river to their objective. The 100th Nisei Battalion was ordered to do what seemed an impossible task. In nighttime darkness, the unit slogged through the knee-deep mud of the flooded riverbank, trying to avoid the thousands of mines. As German fire opened up on the opposite bank, the Nisei huddled along a 2-meter-high (8 ft) stone dike, where they were pinned down. The next day was spent merely trying to survive. The following morning, the 187 men of B Company attempted an advance but were repelled. Only 14 managed to return to the dike. Told to withdraw, the 100th tried again some days later to capture Hill 165, which commanded the road leading up to Monte Cassino. The Nisei held for a short while until lack of support forced another retreat. The Allies had no choice but to bomb the magnificent monastery into rubble. On February 15, Pope Pius XII finally gave the go-ahead to pulverize the abbey. But the stubborn Germans dug in deeper among the ruins. The Japanese boys charged again, but though they had the courage and aggressiveness, they had been badly damaged by three weeks’ fighting. In one attack, a platoon of 40 men returned only with five. The entire 100th was down to 512 men from an original 832. They were already halfway up the mountain but simply couldn’t go on for lack of support. For their sacrifices, the 100th became known as the “Purple Heart Battalion.” Monte Cassino was a heartbreaking loss for the brave Nisei, yet they almost succeeded. The mountain was not to fall to the Allies until May 17, 1944.

7Kasuo Masuda’s Last Patrol

On the day of the Pearl Harbor attack, December 7, 1941, Gensuke Masuda, a farmer from Orange County, California, was thrown into jail by the sheriff. No charges were filed, and 10 days later, after being interrogated by the FBI, he was interned at Ft. Missoula, Montana. Eventually his entire family was forcibly incarcerated along with him. Masuda had never committed an act of disloyalty against the United States. He had always considered it his country and raised his children as Americans. Four sons would serve in the US armed forces. One of them, Kazuo, was shipped to Italy with the 442nd Regiment. Two years earlier, Kazuo had implored officials in a letter to release his family, but it fell on deaf ears. Nevertheless, Kazuo entered combat with his loyalty undiminished. On July 6, he manned an observation post as the 442nd advanced on Hill 140 near the town of Pastina. Coming under heavy fire from the Germans and lacking firepower, Masuda spotted a mortar tube 200 meters (600 ft) away. Amid withering fire, Masuda crawled to retrieve it and 20 rounds of ammunition then returned to his post. Using his dirt-filled helmet as a base plate, Masuda single-handedly fired on the enemy for 12 straight hours, repelling two big counterattacks. On August 27, Masuda and two companions undertook a night patrol of a booby-trapped and mine-infested area of the Arno riverbank. Sensing movement nearby, Masuda discovered too late that the Germans had them surrounded. He ordered his men to slip away as he held back the enemy. Masuda died, but his sacrifice enabled his companions to escape with valuable intelligence that aided the Allies in crossing the Arno. The Masuda family was released in July 1945. Returning to Orange County, the Masudas were threatened with bodily harm if they tried to settle down. Sympathetic members of the community rallied behind the Masudas, which led to a backlash against discrimination toward Japanese Americans. Gen. Joseph Stilwell presented Kazuo’s posthumous Distinguished Service Cross to the family. An Army Captain named Ronald Reagan said: “Blood that has soaked into the sands of a beach is all of one color. America stands unique in the world, the only country not founded on race, but on a way—an ideal. Not in spite of, but because of our polyglot background, we have had all the strength in the world. That is the American way. Mr. And Mrs. Masuda, just as one member of the family of Americans, speaking to another member I want to say for what your son Kazuo did—thanks.”

6The Lost Battalion

In late October 1944, the Allies were closing in on Germany’s western frontier. Around the densely wooded and difficult terrain of the Vosges mountains in Northern France, the battle had turned into a slugging match, from tree to tree and ridge to ridge in fog and rain. The 1st Battalion of the 141st Texas Regiment found itself cut off and surrounded by the Germans, its food and supplies running dangerously low. Major General John Dahlquist pulled out the 442nd from its rest behind the lines to save the Texans. With Adolf Hitler himself ordering the Germans to prevent rescue at all cost, the ensuing fight proved one of the bloodiest in US Army history. In such a battle at close quarters, the Japanese Americans were in constant danger of being hit by friendly artillery fire. In some engagements, they were outnumbered four to one. In tense cat-and-mouse situations, firing their weapons risked betraying their positions to camouflaged German machine gun nests and snipers. After four days of almost nonstop action, the Nisei approached the Texans from two sides. Pvt. Barney Hajiro (screaming “Banzai!”) led the bayonet charge up what came to be known as Suicide Hill for the large losses the Nisei sustained. Hajiro ran 100 meters (300 ft) through the hail of bullets and across a booby-trapped area to single-handedly take out two German machine gun nests. “We yelled our heads off and charged and shot the head off everything that moved,” recalled Pfc. Ichigi Kashiwagi. “We didn’t care anymore . . . We acted like a bunch of savages.” Pvt. George Sakato saw his best friend die by his side. In his rage, he plunged heedlessly into a German counterattack, killing 12, wounding two, and capturing four of the enemy. The Germans were shaken by the banzai charge and left the hill to the Japanese. On October 30, the Nisei finally reached the Texans. The 442nd suffered over 100 dead and 1,000 wounded to rescue 211 men.

5Bob Kubo: The Cave Flusher

On the other side of the globe, in the Pacific, Nisei linguists served with equal distinction as their comrades in Europe. In Saipan, Hoichi “Bob” Kubo worked as a “cave flusher,” one of the most dangerous jobs around. He would penetrate the island’s deep lava caves to search for hidden Japanese civilians. Japanese propaganda had told the inhabitants that the Americans would torture and rape them if captured. The terrified people preferred to commit suicide than fall into the hands of US soldiers. Shocked Americans came upon piles of bodies, including young women and their babies, at the bottom of the cliffs from where they had thrown themselves. Many sought refuge in caves, where they would sometimes be joined by desperate soldiers. As a linguist, it was Kubo’s job to dispel the propaganda by directly speaking to the civilians in the caves. Since propaganda had also spread the lie that all Japanese in the US had been executed after Pearl Harbor, Kubo’s appearance helped assure people that what they had heard was false. One day in July 1944, Kubo, armed with only a pistol, entered a cave where 122 women and children held hostage by eight soldiers waited, ready to commit suicide at the approach of the Americans. Disarmed by the sight of a Japanese face, the soldiers listened as Kubo explained that they had nothing to fear. Building rapport with the trapped Japanese, he shared his C-rations and told the commander that his grandfathers had fought in the Russo-Japanese War, thus gaining his respect. The soldiers asked Kubo how he could serve the enemy Americans. Kubo replied by quoting from an ancient Japanese story about a son meeting his father on the battlefield. When the father asked his son how he could fight him, the son replied, “If I am filial, I cannot serve the Emperor. If I serve the Emperor, I cannot be filial.” The soldiers understood Kubo’s point that, though both his parents were Japanese, he owed a higher loyalty to the country of his birth, America. After two hours, the soldiers surrendered, and Kubo emerged from the cave with all the civilians and soldiers alive. He continued to save lives during the murderous battle of Okinawa. Kubo was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross and eventually ended the war the most decorated Nisei in the Pacific theater.

4Richard Sakakida’s Epic Prison Break

In October 1943, 500 Filipino guerrillas were sprung from Bilibid Prison in one of the largest jailbreaks of World War II. The man behind the operation was a Nisei spy named Richard Sakakida. A native of Maui, Sakakida was recruited by US Intelligence in early 1941 to use his knowledge of Japanese language and culture to infiltrate the Japanese community in Manila to identify possible military agents. Together with fellow Nisei Arthur Komori, Sakakida was able to gather valuable information about Japanese designs on the Philippines. After Pearl Harbor, both Komori and Sakakida were thrown into prison by Filipinos who were unaware that they were American citizens. Their superior at Military Intelligence got them out, and they made their way to Bataan, where the Filipino and US forces were making a desperate last stand against the Japanese invaders. Here, they interrogated captured Japanese, translated confiscated documents, and deciphered enemy codes. Bataan fell. Realizing that the island bastion of Corregidor was also doomed, Komori escaped to Australia, but Sakakida opted to stay behind. Sakakida was brutally tortured by the Japanese Kempetai (secret police). As an ethnic Japanese, he faced the death penalty for treason. Fortunately, the Japanese figured they could use Sakakida, who had always denied he was ever a spy, as a translator and all-around assistant at 14th Army HQ. Incredibly, the Japanese were so lax about security at HQ that Sakakida was able to gather information from documents left carelessly around. How to transmit it to the Allies was another matter. Opportunity came when Sakakida became acquainted with the wife of jailed guerrilla leader Ernesto Tupas, who had come to HQ to ask for a visitor’s pass to Bilibid Prison. Through her, Sakakida got in touch with Tupas’s men, and together they planned to liberate Tupas from prison. Donning a Japanese officer’s uniform, complete with medal ribbons and a sword, Sakakida and four Filipinos dressed as Japanese soldiers strode into Bilibid. Barking orders at the guards, he had them open the gates. Then all the lights blacked out as part of a prearranged plan. Amid the confusion, a larger force of guerrillas stormed in and opened the cell doors. Ernesto Tupas was free. Tupas returned to the mountains, where he established radio communications with Gen. Douglas MacArthur in Australia. He relayed the information Sakakida was supplying from the very heart of enemy headquarters. The intelligence helped thwart a Japanese land invasion of Australia. With the smashing successes of the American reinvasion of the Philippines, Sakakida came increasingly under suspicion. He decided it was time to escape. Braving the surrounding jungles, he endured wounds, disease, and starvation until he was finally rescued by a US patrol. After the war, Richard Sakakida was awarded the Bronze Star, Legion of Merit, and the Commendation Medal. He was inducted to the Military Intelligence Corps Hall of Fame in 1988.

3The Gothic Line

After the Allies captured Rome, German Field Marshal Kesselring had his forces fall back on the last defensive position to block the approach to Austria, the seemingly impenetrable Gothic Line. This forbidding series of fortifications stretched from the Ligurian Sea inland through mountaintops, rising ever higher, culminating in the 1,000-meter-high (3,000 ft) Mt. Altissimo. For five months, the US 5th Army had been pounding the Gothic Line without much progress. By this time, the 442nd had earned a reputation for pulling off near-impossible assignments. It was decided to send the Nisei back to Italy to help crack the Gothic Line and break the stalemate. The Nisei had to take the Germans by surprise, so they moved into their assault positions in total silence at night. The troops climbed a sheer cliff face, weighed down by backpacks laden with supplies and ammunition. Some men slipped and fell without making the slightest sound that might alarm the Germans. As dawn of April 5, 1945, broke, they still were not aware that the Japanese were already just below their fortifications, ready to spring. The Nisei attack caught the enemy totally off guard—half of them were still asleep. Nevertheless, the German reaction was swift. Guns and grenades began to greet the attackers who pressed on, taking one strongpoint after another. The battle was over in about 30 minutes. That first day, the Germans suffered 30 killed and more wounded and lost a dozen fortified bunkers, 17 machine guns, and three 75-mm howitzers. From this foothold, the Allies captured the rest of the other mountaintops in the following days. The reduction of the vaunted Gothic Line was an accomplished fact by April 7.

2Sadao Munemori’s Sacrifice

As a child, Yaeko Munemori was in the habit of taunting her younger brother Sadao as a good-for-nothing in their playful tussles. One day, an exasperated Sadao told Yaeko, “You just wait. When I grow up, they’re going to name a ship after me. And I’m not going to let you ride on it.” The tomboyish Yaeko replied, “I don’t care. I wouldn’t ride on your ship anyway.” Yaeko and Sadao came from a brood of five children, all born in Los Angeles. Their father Kametaro arrived in California from Hiroshima at the turn of the century. Living with discrimination was painful. Once, young Sadao was turned away from a swimming pool by a sign: “NO JAPS ALLOWED.” Kametaro died in 1938 and was not there to witness his family uprooted in the wake of Pearl Harbor and sent to a relocation camp. Having enlisted in the Army a month before the attack, Sadao spent two years training in various locations. Observing his fellow recruits and comparing himself to them, Sadao came to the conclusion, “I’m just a good-for-nothing like Yaeko used to say.” Sadao was assigned to the 100th Battallion and arrived in Anzio in May 1944. From Italy, the 100th/442nd saw action in France before being brought back to Italy to take the Gothic Line. “Do be careful,” Yaeko wrote her brother. Three days later, Sadao’s Company A led the assault that April morning. As the Germans recovered from the shock and fought back, Sadao’s squad leader fell, injured. Pfc. Munemori took over, and with two other men crawled into the shelter of a shell hole as machine guns belched fire. Grenades rained around the crater as Sadao climbed out to attack the two machine gun posts alone. He silenced the enemy with grenades and crawled back to the crater, at which point a grenade bounced off his helmet and landed in the hole. There was no time to run away or throw the grenade out. In a split-second decision, Munemori threw himself over the grenade and absorbed the full force of the blast. Death was instantaneous. Sadao had saved the lives of two men at the cost of his own. Sadao had written Yaeko from France: “All of us boys are already thinking of the future and the fellows want me to come to Hawaii and visit them for sure. That’s one thing that I’ll have to do when I return. You know how I couldn’t get along too good with Japanese boys back home. Well I can get along pretty good with these guys because they don’t try to hold back anything. Yes, Keech! I’m gonna have to visit them after the war.” Tragically, it was not to be. Pfc. Sadao Munemori was the only Nisei to be awarded the Medal of Honor during the war. In 1948, the troopship that bought the Nisei boys back home was renamed the Sadao Munemori. When it docked in Honolulu, Yaeko was the first to be invited aboard it. Sadao would have been very happy.

1Daniel Inouye Fights With A Severed Arm

Daniel Inouye had dreams of becoming a doctor when the Pacific War broke out. Inouye had always thought of himself as a pure American. When he was 15, he was expelled from his Japanese-language school for protesting when his instructor expressed anti-Christian and pro-Japanese political sentiments. On the morning of the Pearl Harbor attack, Inouye was a first-aid worker for the Red Cross and worked five straight days tending to the wounded. The 17-year-old immediately went to enlist in the Army but was turned away with a 4-C classification: “Enemy Alien.” Inouye’s patriotism wasn’t dampened, and when the all-Nisei 100th and 442nd were created, Inouye signed up. In the fight to rescue the Lost Battalion, Inouye was shot near the heart, but his life was saved when two silver dollars in his pocket that he won in a poker game stopped the bullet. He kept the coins as good luck charms. On April 21, 1945, Inouye’s unit was tasked to capture a ridge near San Terenzo, Italy, that served as a strongpoint of the Gothic Line. That morning, Inouye couldn’t find his silver coins. With a sense of foreboding, he told a friend, “Today’s my day. I’m going to get it.” Three German machine guns pinned down Inouye and his men as they advanced. Inouye stood up and was shot in the stomach. The severe wound did not stop him from annihilating the first machine gun post. Refusing treatment, Inouye led an attack against the second one and took it before collapsing from loss of blood. Rallying himself, Inouye approached the final bunker. As he raised his right arm to throw his last grenade, his elbow was shattered by a shot from the bunker. For a few seconds, there was the danger of his injured fist involuntarily relaxing and dropping the grenade, and Inouye yelled at his men to step back. Meanwhile, the German in the bunker was reloading to finish him off. With his left hand, Inouye pried loose the grenade from his right and hurled it in time at the German. He mowed down the rest of the enemy with his Thompson before a dying German gave him another bullet in the leg. Inouye fell unconscious at the bottom of the ridge. When he came to, his men were gathered around him. Inouye ordered them back to their positions. “Nobody called off the war!” he cried. Inouye had single-handedly killed 25 of the enemy. When Inouye finally got to the field hospital, he had to be given 17 blood transfusions. His mangled arm had to be amputated without anesthesia as doctors feared giving him more morphine could lower his blood pressure enough to kill him. They didn’t even notice Inouye’s leg wound until later because he was so covered with blood. Inouye’s actions earned him the Distinguished Service Cross, upgraded to Medal of Honor in 2000. But losing an arm ended Inouye’s ambition to become a surgeon. He turned instead to politics and eventually served as a Democratic senator from Hawaii. In 2010, Inouye became President Pro Tempore of the Senate, making him third in line in the succession for the US presidency. Larry is a freelance writer whose main interest is history.