10First Chemical Warfare Victims Ever Found

With great power comes great enemies. The Romans were reminded of this in A.D. 256, when the cunning army of the Persian Sasanian Empire captured Dura, a Roman fortress-city in what is now eastern Syria. As a way to invade the fortress, the Persians dug a deep mine to cause a city wall and tower to buckle. The Romans tunneled from the other side to intercept them. When they met, the Roman countermine was above the Persian mine, creating a shaft like a chimney between the two. With no written records, what happened next is somewhat unclear. In the early 1900s, archaeologist Robert du Mesnil du Buisson discovered a pile of 19 Roman bodies in the mines. Only one Persian body was nearby. Du Mesnil believed the soldiers had engaged in a vicious battle, causing the Romans to fall back into their tunnel. Then the Persians set that tunnel on fire, which supposedly killed the Romans. But Simon James, an archaeologist from the University of Leicester, offered a different theory in 2009. “This wasn’t a pile of people who had been crowded into a small space and collapsed where they stood,” he said. “This was a deliberate pile of bodies.” According to his view, the Persians heard the Romans digging and ignited a fire to meet them. Then, the Romans opened the shaft between the two mines. James doesn’t know if the Persians directed smoke with a bellows or let the smoke rise naturally through the shaft. But archaeologists did discover sulfur and bitumen in the mine, possibly making these bodies the first chemical warfare victims ever found. James believes the Persians deliberately threw these chemicals in the fire to create deadly fumes, which became sulfuric acid in the lungs of their enemies. The one dead Persian soldier probably set the fire and couldn’t get out in time. James believes any Roman soldiers outside the countermine would have seen the smoke, realized their comrades were dying, and avoided entry. Meanwhile, once the smoke cleared, the Persians quickly piled the bodies like a shield in the countermine and destroyed it. Then they resumed trying to enter the city. Their mining efforts didn’t work to collapse the walls, but the Persians eventually got in anyway. They killed some residents and deported the rest to Persia. At that point, Dura was abandoned forever.

9Shackled Skeletons At Roman Necropolis

In southwest France about 250 meters (820 ft) from the Saintes amphitheater used for gladiator battles, a large Roman-Gallo necropolis has been discovered with the remains of hundreds of people, including five shackled skeletons. Three adults had iron chains around their ankles, one adult had a neck shackle, and a child had a shackle on the wrist. Archaeologists believe these shackled skeletons may be the remains of slaves killed in the arena. Gallo-Roman refers to the period when the Roman Empire ruled the area we now know as France. As a regional capital, Saintes was a bustling town with an amphitheater capable of holding 18,000 people during the first and second centuries, when these individuals are believed to have died. Some graves contained two people, often buried head-to-toe in trench-like pits. However, the necropolis yielded few artifacts. One man had some vases lying beside him, and one child had coins on his or her eyes. The coins were supposedly to pay a ferryman to transport the child’s spirit safely across a river that led from the land of the living to the afterlife. Archaeologists hope to figure out how these people died, if they belonged to the same community, and what their social standing was. In 2005, shackled skeletons were also found in a graveyard excavation from Roman days in York, England. Some of those human remains had bite marks, indicating they may have died in the arena from attacks by wild animals.

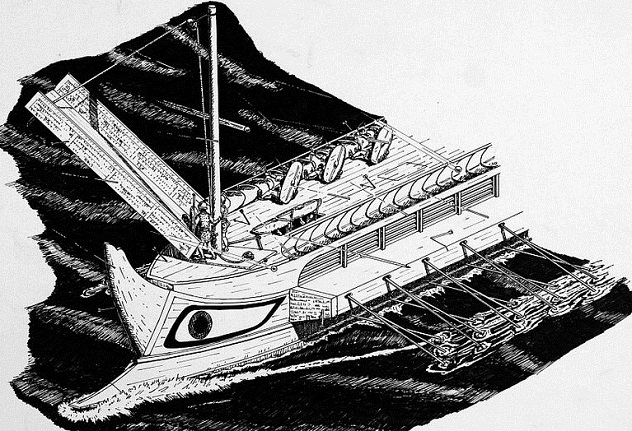

8Relics Of The First Naval Battle Site Ever Found

At the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea, archaeologists continue to excavate relics from the first naval battle site ever found. Lasting only a few hours, the Battle of the Egadi Islands off the coast of western Sicily ended the 23-year First Punic War between the Romans and the Carthaginians of North Africa in early March 241 B.C. With their 300 maneuverable ships, the Romans ambushed the enemy fleet and blocked their route. Only 250 of the 700 Carthaginian vessels were warships; the rest carried supplies. By the end of the swift battle, 70 Carthaginian ships were captured, 50 were sunk, and the remainder were able to escape. This conflict also changed history by propelling the Roman Republic toward its military future as an empire. The underwater site is about 5 square kilometers (2 mi2) and so far has yielded weapons, bronze helmets, tall Roman jars (called “amphorae”), and especially bronze battle rams. A ram is a part of a warship that extends from the bow to pierce the hull of an enemy ship. (You can see the ram in the picture above, as well as a boarding bridge being lowered.) Until this site was discovered, only three rams had been found worldwide. Now, there are at least 14. “Much of what we knew about ancient naval battles and ancient warships was based on historical text and iconography,” said archaeologist Jeffrey Royal. “We now have physical archaeological data which will significantly change our understanding. [These] rams were not just used as weapons, they were there to protect the ship. The discovery of these rams will help us learn more about the size of these ships, the way they were built, what materials were used as well as the economics of building a navy and the cost of losing a battle.” So far, we’ve learned that the warships were 30 percent smaller than originally believed. At only 28 meters (92 ft) long, it’s unlikely that they were triremes, warships propelled by three tiers of oarsmen on each side. The excessive height would have made the ships unstable. We’ve also discovered that a ram’s weight of 125 kilograms (275 lb) made it capable of slicing through a ship, not simply punching a small hole in its side. That means a damaged ship would shatter on the surface instead of sinking in one piece.

7The Abduction Of The Sabine Women

Titus Livius (also known as “Livy“), one of the great historians of Rome, recorded events in moral terms of the individual to reveal character, supposedly without political influence. According to the Livy’s account, Rome was founded by twins Romulus and Remus in 753 B.C. After a dispute, Romulus killed Remus and became ruler of Rome, which was named for him. To make the town grow, Romulus took in fugitives and outcasts from other areas, but they were mostly men. Rome became powerful enough to prevail in battles with violent neighbors. However, without enough women to produce children, Rome’s growth and power was expected to end in one generation. Romulus sent representatives to neighboring communities to ask for young women to marry the men of Rome. But these emissaries were turned down, sometimes in an insulting manner. This didn’t sit well with his men, so Romulus devised a crafty way to get the women he needed. He invited his neighbors to a grand celebration of Consualia, with games and sacrifices to honor the god Consus (also known as Neptunus Equestris). Many of Rome’s neighbors attended, including the Sabines, who brought their wives and children. All were impressed by Rome’s growth. During the festival, Romulus gave his men a prearranged signal to abduct the maidens. The Sabine parents escaped without harm but were obviously distraught by what had happened. Meanwhile, Romulus visited each abducted woman to let her know that she would have the full status, rights, and material reward of a Roman wife and that her husband would treat her well from then on. About a year later, the Romans and the Sabines went to war over the women. But the Sabine women were now content to remain Roman wives, so they interceded between the two sides in the midst of battle and brought about peace. After a treaty was signed, the two sides united under Roman rule, making Rome even stronger. However, Livy’s historical accounts are mixed with legend, especially in the early days of Rome, which makes it difficult to know how much of his writings are true.

6The Sudden Disappearance Of The Gateway To Rome

Between the second and sixth centuries, Portus was a valuable Roman harbor at the mouth of the Tiber River, where as many as 350 ships could dock at one time. Through Portus, the Romans received olive oil, wine, wheat, luxury goods, and slaves. This shipping hub was so important to them that they built one of their most elaborate palaces there, adorned with exquisite artwork such as mosaics and frescos and extending over several acres with walls up to 15 meters (50 ft) high. They also built an amphitheater and a massive warehouse, possibly for the construction and maintenance of ships for commerce and war. However, in the sixth century, as the Roman Empire was crumbling, the grand palace and massive warehouse were abandoned, with the structures appearing to vanish. By this time, the Roman Empire had been divided into two halves. With Byzantium (Constantinople) as its capital, the Byzantine Empire became its eastern half, fighting against marauders like the Ostrogoths to control Rome. Archaeologists from the University of Southampton, who are excavating the Portus site, have a theory as to what happened. “By the sixth century, the Byzantines felt the port could be a threat as it was vulnerable to being occupied by the Ostrogoths, so they took the decision to destroy it themselves,” said Simon Keay, who headed the dig. Rather than allow their enemies to dock in the great port, archaeologists believe the Byzantines flattened the structures, methodically pulling down each pillar and wall until nothing usable remained.

5Roman Military Camps Outside The Empire

Beyond the Empire’s northern frontier along the Rhine River, the Romans had repeatedly tried to conquer unruly German tribes but were unsuccessful. That didn’t stop the Romans from boasting in written records that their military occasionally pushed into Germany, most likely to retaliate for German attacks in Roman territory. Until recently, many historians believed it was just empty talk. However, in 2010, an 18-hectare (44 acre) Roman military camp was accidentally discovered in eastern Germany near the village of Hachelbich when land was being excavated to build a road there. The camp may have accommodated up to 5,000 soldiers. Combined with the 2008 discovery of another battlefield around Hannover, the encampment at Hachelbich suggests that the written reports are true. Many elements of the camp are consistent with construction and use by the Roman military. Surrounded by trenches about 1 meter (3 ft) deep, the area is a rectangle with rounded corners. As part of the perimeter defense, a dirt wall was erected with tall stakes on top to make a 3-meter-high (10 ft) barricade. The actual wall is gone, of course, but archaeologists could see discolorations in the ground where it used to stand. They also found nails from Roman boots, bread ovens, and a few other Roman artifacts that appear to be from the first and second centuries. “Now we have the first camp that’s clearly more than a day trip from the edge of the empire,” said Michael Meyer, an archaeologist from the Free University of Berlin. “It’s no isolated frontier outpost but something that clearly points to the Elbe River [deep in German territory].”

4Roman Head-Hunting

Executed criminals, Roman gladiators, or war trophies? That question has yet to be answered about the 39 male human skulls discovered in the late 1980s in a burial pit near a Roman amphitheater and Walbrook stream in London. These men, most of whom were 25–35 years old, led hard lives judging by the evidence of decapitation, fractures, sharp-edged weapon injuries, and blunt-force trauma on their skulls. Their deaths have been dated to 120–160 when Londinium (now London) was a thriving capital in Roman Britain. Immediately after the skulls were unearthed, there was no money to analyze them in depth. For decades, they sat untouched at the Museum of London, until bioarchaeologist Rebecca Redfern and earth scientist Heather Bonney did a more thorough analysis a few years ago. They published their findings in early 2014 in the Journal of Archaeological Science. Although the skulls don’t look as though they were mounted on posts, the researchers believe they may have been exhibited in the Londinium amphitheater after the men died. They could have been thrown into the burial pit later. But Kathleen Coleman, a Roman gladiator expert from Harvard, disagrees. Without gravestones proving these men were gladiators, she believes they may have been killed in riots, common assaults, or gang warfare. Redfern doesn’t buy that argument. “There is no evidence for social unrest, warfare, or other acts of organized violence in London during the period that these human remains date from,” she said. “[Instead, there are] two possible outcomes—that these are fatally injured gladiators, or the victims of Roman head-hunting—a tantalizing prospect.” Were these head-hunting trophy skulls, such as those displayed by the military at Hadrian’s Wall in Roman Britain? The archaeologists want to do isotope analyses to determine where these men resided originally. The answer to whether they were locals or distant strangers may help scientists to narrow the possibilities of how and why they died.

3The Mystery Of The Bar Kokhba Revolt

Simeon bar Kokhba was a Jewish leader who spearheaded an unsuccessful rebellion against the Roman Empire in Judea Province around 132–136. The exact reasons for the revolt have been a mystery to historians, but many suspected that the Romans’ harsh treatment of the Jews was the primary cause. In mid-2014, a new archaeological clue was discovered in Jerusalem by the Antiquities Authority as they excavated north of Damascus Gate. They found a large limestone fragment that commemorated Roman Emperor Hadrian, who ruled from 117–138. Originally, the stone slab may have been part of a gateway. But at some point, it had been recycled into a floor around an opening for a cistern. This new find is the right half of a full inscription; the left half was discovered in the 1800s. Dedicated to Hadrian in 129–130 by Legio X Fretensis, a Roman legion, the clear Latin inscription on the slab has been translated into English: “To the Imperator Caesar Traianus Hadrianus Augustus, son of the deified Traianus Parthicus, grandson of the deified Nerva, high priest, invested with tribunician power for the 14th time, consul for the third time, father of the country (dedicated by) the 10th legion Fretensis Antoniniana.” This inscription is important because it provides Hadrian’s name and titles and a date. In Jewish history, Hadrian is infamous for the “Hadrianic decrees” that persecuted Jews and forbade them to practice their faith. The date confirms that the Roman 10th Legion was in Jerusalem just before the Bar Kokhba revolt. The inscription may also allude to a reason for the uprising: the creation of a Roman colony in Jerusalem, “Aelia Capitolina,” which appears to be named after Hadrian, whose complete name is Publius Aelius Hadrianus. “There is no doubt that the discovery of this inscription will contribute greatly to the longstanding question about the reasons that led to the outbreak of the Bar Kokhba revolt,” said Dr. Rina Avner, who led the excavation. “Were the reasons for the rebellion the construction of Aelia Capitolina and the establishment of the pagan temple on the site of the Jewish Temple Mount; or conversely perhaps, these were the results of the revolt—that is, punitive action taken by Hadrian against those who rebelled against Roman rule?”

2The Lost Roman Legion At Liqian

How did so many natives of a remote Chinese village come to possess Caucasian features like hooked noses, blonde hair, and green or blue eyes? The ancient mystery has generated an ongoing controversy that shows no signs of abating, especially when that impoverished town is trying to strike tourism gold in modern times. As we previously discussed, a legend says some members of a defeated Roman legion founded the town called Liqian (which means “Rome”) in what is now Gansu Province in China. The theory originated with Homer Dubs of Oxford University in the 1950s. According to Dubs, it all started in 53 B.C. when Roman General Marcus Licinius Crassus led his men into the Battle of Carrhae in what is now Turkey against much stronger archers from the Parthian Empire. In a crushing defeat for the Romans, the Parthians killed 20,000 Roman soldiers and captured 10,000 more. Dubs believed that some of the captured soldiers escaped and became mercenaries for the Huns. In 36 B.C., when the Huns were defeated in the Battle of Zhizhi in Kazakhstan by Chinese troops from the Western Han Dynasty, 145 Romans were tapped to guard the newly created town of Liqian. But there’s no physical proof of this. No Roman artifacts such as money or weapons. No definitive DNA proof that today’s Liqian residents are related to the ancient Romans. In 2005, DNA tests showed that the Liqian villagers were 56-percent Caucasian, but it’s not proof of a direct link to a Roman legion. Later DNA testing may be interpreted as severing the link when researchers drew this conclusion: “Overall, a Roman mercenary origin could not be accepted as true according to paternal genetic variation, and the current Liqian population is more likely to be a subgroup of the Chinese majority Han.” But the debate rages on. In 1989, the ancient ruins of a settlement were discovered outside Liqian from the time in question. However, Chinese authorities stopped the research at that time because of political strife after the massacre at Tiananmen Square. Now, the Chinese and the Italians are working together to find a Roman link to Liqian’s residents by resuming the dig for archaeological evidence.

1Mysterious Remains At Ham Hill

South Somerset at Ham Hill is a modern country park where people walk their dogs and enjoy picnics. Here, archaeologists secured special permission to excavate a mysterious site at Britain’s largest hill fort from the Iron Age. The ancient purpose of the 88-hectare (217 acre) site is unknown. Some people think it was constructed for defensive purposes, but researchers say it’s too big to defend properly. They believe it was probably a monument of some sort to bring the community together. Nevertheless, the biggest mystery concerns the ancient remains of hundreds or thousands of people who may have been massacred by the Romans in the first or second century as they began to invade Britain. Certainly, there’s evidence of a Roman military presence with the discovery of ballista bolts among the remains. A ballista looks like a mounted crossbow, but it launches bolts that are as sharp as arrowheads although much bigger. It’s possible that the Romans killed members of the indigenous tribes while policing them. But the strange part is that the corpses were then either chopped up or stripped of their flesh. Typically, Romans didn’t do that, although ancient Britons did. The researchers have two theories. The first one says that the Romans killed these victims, then the local people dealt with the bodies in their traditional manner. The second theory says that a neighboring clan is responsible for the murders. So far, the excavations have simply added to the Roman mystery instead of resolving it.