10 Athens Didn’t Invent Democracy

If there’s one thing we all remember from Western Civilization 101, it’s that Athens invented democracy. Not many of us remember the exact date (480 B.C.), but we remember the invention all right. And yet 18 ancient Greek city-states possessed a democratic government before Athens. Evidence says some of those states had democracy as much as a full century earlier. It seems that Athens, rather than inventing a more egalitarian form of government, actually reacted to a larger Hellenic trend, implementing an already tried-and-true type of governance. The city-state of Ambracia, for example, was ruled by a popular assembly starting in 580 B.C. And these democratic predecessors weren’t obscure cities. City-states like Syracuse and Elis—the city that hosted the ancient Olympics—are among those that beat Athens to the democratic punch. Syracuse and Elis were also the models for many successive democracies in their respective regions (Sicily and the Peloponnese). Athens gets all the credit mostly because more sources cover it, making it the easiest ancient Greek city-state to study. About one-third of nearly every Greek history book is devoted to Classical Athens thanks to the surviving literary riches from that city. Assigning the honor of the “first democracy” to Athens is like declaring Abraham Lincoln America’s “first president” because we have more photos of him than we do of George Washington.

9 Emperor Nero Was Incredibly Popular

In prior articles, we’ve dispelled the myths that Nero fiddled while Rome burned and that he was a stark-raving loon, but there is at least one more misconception about Nero. Today, Nero is remembered as one of Rome’s maddest and most reviled tyrants. Yet the Roman public actually adored Nero during and after his life. Though Nero persecuted the Christian minority who later came to dominate the empire and shape Western memory, Christians were just that: a minority. The rest of Rome loved him. The emperor was so popular with the rest of the Roman public that many had themselves buried with portraits of Nero even long after he died. He was especially beloved compared to his successors. It didn’t hurt that during his lifetime, he led relief efforts during the Great Fire he didn’t start. The emperor also made it known that he vastly improved the food distribution system for the poor. After his untimely death in a coup, Nero developed an Elvis-like following. Across the empire, people sighted Nero, widely believing he had not died. They thought he was in exile, waiting for the right day to return and liberate Rome from boring, short-lived emperors like Otho and Galba.

8 Caligula Didn’t Go Mad (Until The 19th Century)

Caligula’s madness seems not to have been accepted as historical fact until the 19th century, when scholars read literary source material uncritically without the benefit of advances in archaeology and numismatics. Reading the scanty ancient literature on Caligula uncritically is a big problem. The stories depicting Caligula’s insanity were all written long after his reign and conform to the common Greco-Roman literary tradition of the “ancient tyrant“—a recurring trope (like the evil stepmother) in ancient Greek and Roman stories. As early as 2,000 years ago, more reliable Roman historians complained about their peers distorting the lives of Caligula and other early emperors out of hatred. And over the past century, four major scholarly biographies have been written on the subject of Caligula (one each by Balsdon, Barrett, Winterling, and Ferril) with three concluding Caligula was sane but youthful and arrogant. The biography that concluded Caligula was insane—Arther Ferril’s Caligula—happens to be the least scholarly and most reliant on literary sources. We have only a single source actually contemporary to Caligula. Philo of Alexandria visited Caligula to petition the emperor for Jewish rights and wrote briefly about the experience in On the Embassy to Gaius. Philo encountered not a madman but a hostile, self-absorbed youth.

7 The Roman Empire Wasn’t Always Filthy Rich

The words “ancient Rome” conjure up an image of unending prosperity and opulence. All that lavish spending and empire-building came at a cost, though, and countless government ministers had to deliver the news of “We’re broke!” to an emperor—who replied, “Again?” The Roman Empire spent a good amount of its existence on the brink of bankruptcy or in the throes of financial crisis. The empire was continually negotiating money supply issues. A shortage of currency hit the empire in its nascent years, in 33 A.D. Diminished state spending followed, which practically killed the Roman economy. The government finally alleviated the disaster when it offered enormous loans at zero interest to promote trade and stave off complete stagnation. Beginning with the reign of Nero and continuing for centuries, Roman currency was repeatedly debased as the empire suffered through bouts of inflation, private hoarding, decreased revenue, and skyrocketing military and administrative spending. By the third century A.D., Roman coin was a bad joke whose actual precious metal content was questionable at best. Things got so bad that the Roman government wouldn’t accept tax payments in its own currency. To remedy this and keep paying the troops, crippling taxes were levied on the masses, which made Roman rule increasingly intolerable. Most Western Europeans became convinced they might be better off under barbarian rulers.

6 The Coalition Against Persia Wasn’t Exactly Willing

If you haven’t seen 300: Rise of An Empire, much of the film’s suspense revolves around whether the multifarious Greek city-states will band together and fight off the Persian invasion. A Greek alliance did ward off the second Persian invasion, and Sparta was very suspicious of Athenian motives. That concludes the documentary portion of 300: Rise of An Empire. Many Greeks, chief among them the Athenians, weren’t satisfied with just sending Xerxes back to Persia. So an alliance stayed intact after the Second Persian Invasion under the guise of liberating the Greeks of Ionia (modern-day Turkey). This alliance became known as the Delian League, although perhaps “alliance,” is the wrong word. Working with Athens to fight the Persians was a matter of choosing one of two evils. Joining the confederacy led by Athens was like joining the mafia: You were in for life. Freedom-loving, democratic Athens ensured cooperation by conquering the cities that tried to leave its coalition. City-states that refused alliance altogether fared even worse. One, the island of Melos, refused, and Athens blockaded it, starved the inhabitants, and then enslaved the surviving women and children. The League’s supposedly shared treasury? Athens eventually just requisitioned that. The rule of Athens became so intolerable that many city-states joined Sparta in a series of wars against the Athens-led Delian League, devastating the Greek peninsula for the better part of three decades. The Peloponnesian Wars only ended when Sparta allied itself with Persia.

5 Many Greek Cities Collected Taxes Via Shame

Most ancient Greek citizens considered direct taxes tyrannical. Cities with republican or democratic governments avoided direct taxation as much as possible. While it was perfectly acceptable to tax non-citizens, such taxes were mostly symbolic, and the revenue was minor enough that it could never pay for armies, temples, columns, or anything else a city might need. Someone had to pay for those things, so the Greeks developed a system that ensured civic commitment. The Greeks believed a wealthy citizen was morally obligated to his city because the city and its laborers enabled the wealthy man to accrue those riches. A duty or debt to the public good was implicit among wealthy citizens in Greek cities. No written law stipulated what a given citizen was to contribute. Service to the community came in the form of construction of common buildings and naval ships, supplying the military, and so on. In theory, a rich man could refuse to contribute at all. Iin practice, however, the weight of expectations was great enough that the shame of refusal compelled the wealthy to support the community. The honor associated with serving one’s city in this way was so great that it inspired competition among the wealthy in Athens. Many citizens took on additional civic or religious projects to assure their prominence within the city and outdo their peers. Who needs tax codes and laws when you have morals, ethics, and shame?

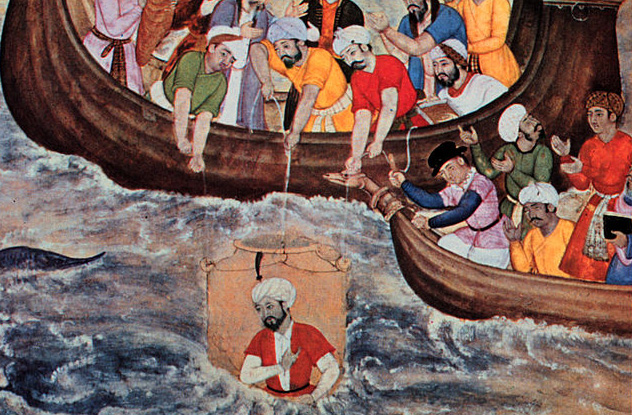

4 Ancient Underwater Exploration

Long before submarines and scuba suits, the ancient Greeks were devising ingenious ways to extend divers’ and explorers’ time underwater. The Greeks pioneered the use of diving bells, which were inverted kettles and barrels submerged with weights. The trapped air displaced the water and created an air pocket, allowing divers to repeatedly return to the bell to breathe without surfacing. If you’ve watched Pirates of the Caribbean, you’ve seen something approaching this. Aristotle recorded the diving bell in use by Greek divers in 360 B.C. About 30 years later, Alexander the Great supposedly manned a similar submersible on multiple occasions. Using either a glass barrel or a barrel with a glass window, Alexander dove with the express purpose of undersea exploration. Later, Alexander used diving bells at the siege of the island city of Tyre. The Romans later made their own contributions to undersea technology. Writing in the late first century A.D., Pliny the Elder described Roman divers using snorkel-like apparatuses to stay beneath the sea’s surface.

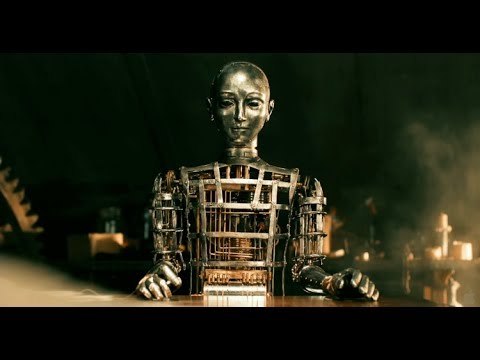

3 Animatronics (And Robots) Are Ancient

The mechanical figures and animals speaking and moving automatically in theme parks all over the world seem like they must be recent inventions. They’re not, however, because 2,000 years ago, Heron of Alexandria was entertaining Greco-Roman Egypt with an incredible array of automata. Heron was a mathematician, engineer, teacher, and all-around scientist who lived and worked in Alexandria during the first century A.D. In addition to writing at least 13 books on mathematics and physics, Heron created automatic spectacles for religious and theatrical purposes. To open and close temple doors, Heron devised a steam-based mechanism that needed only a lit brazier to operate. As impressive as that is, it pales in comparison to Heron’s automatic theaters. Using sand as a timer to operate a system of hidden weights, Heron created a theater of miniatures that was programmed to act out an entire play. Dolphins leaped and dove, nymphs danced, ships sailed, and puppet-sized figures entered and exited the stage. And none of the movement required human intervention beyond the initial switch. Heron even staged battles between large figures of Heracles and dragons. His most impressive achievement might have been his programmable robots that used counterweight motors and carefully arranged ropes to dictate the figures’ and contraptions’ movement patterns. The scope of Heron’s inventions is enormous, and their mechanisms resist neat summary. Detailed enough records exist of his automata that modern researchers have recreated some of them successfully.

2 Alexander Transformed The Island Of Tyre Into A Peninsula

While there’s some debate as to whether the Macedonian conqueror counts as Greek, there’s no denying his central place in later Greco-Roman culture. After conquering Asia Minor, Alexander the Great turned his attention toward the Levant in 332 B.C. At this point, Alexander possessed a fine army, but he lacked naval power. Thus, it seemed the important island city of Tyre might be unconquerable for the conquest-minded Alexander. Located just off the coast of what is now Lebanon, Tyre’s defenses extended beyond its island geography. Even if Alexander could somehow cross the kilometer of water separating Tyre from the mainland, his army would still have to contend with the city’s 45-meter (150 ft) walls built on the edge of the sea to prevent landings. And then there were Tyre’s defenders—tens of thousands of them. Undaunted, Alexander had his engineers embark on one of history’s greatest siege works: a 60-meter-wide (200 ft) land bridge connecting Tyre to the coast. Since Alexander’s builders had to work within range of Tyre’s catapults, the Macedonians constructed two mobile 45-meter-tall (150 ft) siege towers to protect the laborers. Despite constant attacks from Tyre’s defenders, the land bridge was completed. Alexander’s capture of another city’s fleet and subsequent use of that armada then ultimately enabled Tyre’s defeat. Alexander’s land bridge, built on a stone foundation, still exists today, connecting Tyre to the coast of Lebanon.

1 Rome’s Amazing Concrete

Modern concrete, unsurprisingly, is 10 times stronger than the ancient Roman variety. Nonetheless, Roman concrete is countless times more durable than modern mixtures. For all its brute strength, the typical concrete of today can’t withstand the elements, especially seawater. Against seawater, erosion sets in after just 50 years. Not so with the blend that the Romans used for their harbors and breakwaters—which, after almost 2,000 years of marine abuse, are still serviceable. Even outside of the water, there’s a significant difference in durability, with many recent concrete structures having been built with only about a century of service in mind. Roman concrete is also significantly more environmentally friendly, using less resources and requiring less heat. The exact recipe for Roman concrete seemed to have been lost to time—until recently. Mineral analysis reveals that Roman builders used an admixture of volcanic ash. Not just any volcanic ash will do, though, and the Romans knew it. Under Emperor Augustus, concrete production was standardized, and concrete was mixed with volcanic ash from carefully chosen deposits. As the Romans built large and enduring structures all over the Mediterranean, they shipped thousands of tons of this volcanic ash to their far-flung builders. And now, thanks to mineral analysis of samples of Roman construction, researchers know the composition of this ash and are unraveling the mechanisms by which this pozzolan ash reacts with saltwater to enhance the resistance of Roman concrete to erosion. If you feel so inclined, you can reach J. here.