10Priestess Of Hathor

While exploring the ancient Nile village of Deir el-Medina, archaeologists discovered an intricately tattooed, 3000-year-old mummy. The find came from an area that once housed workers who built the Valley of the Kings. Advanced imaging technology revealed 30 separate inkings across the mummy’s back, neck, arms, and shoulder. Designs include eyes, snakes, lotus blossoms, and cows. Many of the markings are linked with the goddess Hathor, leading to her nickname: Priestess of Hathor. The Priestess of Hathor’s tattoos are the oldest representative image tattoos in Egypt. Earlier Egyptian body marking are in the Nubian style—dots and lines formed into abstract geometric designs. Their Priestess’s designs differ. They are clear and easily identifiable depictions of real-world objects. Divine imagery in prominent positions on her body indicates they were most likely for religious cult activity.

9Filipino Fire Mummies

Mummies from the caves around Kabayan, Philippines, have been preserved through fire. Archaeologists believe the mummies belong to the Ibaloi tribe and date to 1200–1500. Smoking corpses over open fires died out around Spanish colonization. Experts suspect the smoke treatment was reserved for tribal leaders. Many fire mummies are covered with tattoos of geometric designs and omen animals like lizards, snakes, scorpions, and centipedes. Some feature circular tattoos around the wrists, which may represent solar discs. Others bear zig-zag patterns. Apo Annu is one of the most intriguing of the fire mummies. In the early 1900s, his intricately tattooed remains were stolen. The locals believed Apo Annu’s absence caused natural disasters like famine, earthquakes, drought, and disease. Eventually, the fire mummy was returned and reburied to reestablish balance.

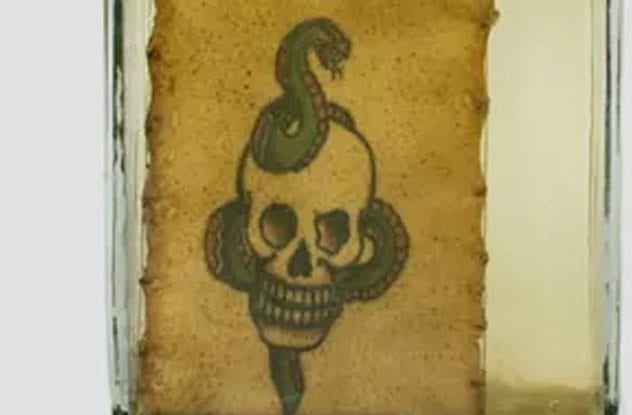

8Preserved Polish Prison Ink

In 19th-century Poland, authorities used to cut tattoos out of deceased convicts and catalog them. The process started to aid in identifying gang affiliations. The Department of Forensic Medicine at Jagiellonian University in Krakow now houses the grisly collection: 60 specimens, carefully preserved in glass jars filled with formaldehyde. Tattoos were strictly forbidden in Polish prisons. However, the inmates got around this through a variety of inventive techniques. Razor blades, glass, and wires, were used to pierce the skin. Ink was made with charcoal, burned rubber, cork, and pencil lead, which was mixed with water, urine, soap, or fat. The tattoos have a complex level of symbolism—the exact nature of which is known only to initiates within this bygone criminal underworld. These markings reveal profession, background, life experience, and even sexual orientation. Religious imagery and explicit scenes are the most common motifs in 19th-century Polish prison tattoos.

7Intimate Secret

In 2014, archaeologists discovered the tattoo of a man’s name on the inner thigh of a 1,300-year-old Sudanese mummy. The intimate inking spells out “Michael” in Greek. Experts speculate that this was a protective symbol of St. Michael the Archangel—not a lover. The symbol of St. Michael has been discovered before on stone tablets and churches but never on flesh. It is unknown whether the tattoo was intended to be seen or to remain a secret. Researchers used CAT scans and infrared technology to peek under the mummy’s wrappings. She is believed to have been between 20 and 35. Her remains were bundled in linen and woolen cloth. Unlike traditional Egyptian mummies, she was preserved naturally in the dry climate. The nature of her inner thigh tattoo indicates that she was part of a Christian community along the Nile.

6Qilakitsoq Mummies

In 1972, hunters discovered a group of mummies near Greenland’s abandoned Inuit settlement of Qilakitsoq. Dating to the Thule culture of the mid-15th century, the group contained a baby, a two-year-old boy, and six women. The cold, dry climate naturally preserved the remains, which were stacked on top of each other with layers of animal fur. The two-year-old suffered from Down’s syndrome, and one of the older women was deaf, blind, and plagued by a malignant tumor. The baby was buried alive. The fate of the other mummies remains a mystery. Tattoos were once commonplace for Inuit women and often signified tribal affiliation. Infrared analysis revealed that five out of the six Qilakitsoq women had tattoos on their faces. Black lines with arched eyebrows were drawn on their foreheads. Dotted tattoos also appeared on two of the women. All five had tattoos on their cheeks and two had tattooed chins.

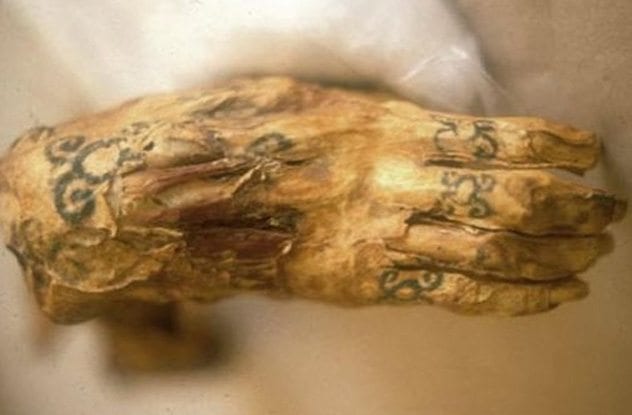

5Therapeutic Tattoos

Tattoos on a 1,000-year-old Andean mummy may represent acupuncture points. Archaeologists discovered the preserved remains unwrapped in the sands around Chiribaya Alta in Southern Peru. Researchers use molecular cytogenic technology to determine it was female and the most advanced imaging to study her tattoos. The mummy bore two distinctive types of tattoos—decorative ones with animal designs and some in a symbolic cipher. The abstract tattoos may have had a ritual, protective, or even healing function. Soot-based ink was used to make images of birds, monkeys, and reptiles. Four of her fingers are tattooed with rings. The marks that are of the most interest to researchers are 12 circular forms on her neck. Some believe these correspond to therapeutic points exploiting in acupuncture for pain relief. A 1999 study of Otzi the Ice Man’s tattoos suggested that his ancient ink might also have served a similar healing purpose.

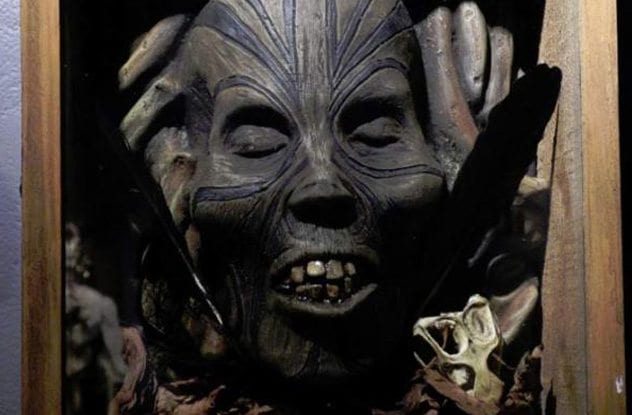

4Mokomokai

In Maori culture, the collective term for preserved, tattooed heads is “mokomokai.” Making these grisly war trophies is time consuming. First, the head is severed and then filled with flax fiber and gum. Next, it is boiled, before smoking over a fire. Once the head is dried in the Sun for a few days, it is finished with a shark oil rub. Mokomaki are covered in moko—ancient Maori tattoos. Generally, only men wore these high-status markings. The art is produced by carving flesh with a chisel-like tool known as an “uhi” and filling in the slices with ink. These were extremely painful and served as a mark of courage and adulthood. One of the most famous mokomai is Toi Moko, which along with 800 similar heads was traded to the British for guns and goods. Toi Moko made it to the Guernsey Museum before returning to New Zealand.

3Razzouk Ink

Jerusalem’s Razzouk family has tattooed Christian Pilgrims for 700 years, and they are still open for business. Their tattoo shop opened in 14th-century Egypt. 300 years later, the Razzouk’s relocated to Jerusalem due to the high demand for holy tattoos. Originally, they applied their sacred designs with a long wooden stick with thick needles attached to it. The process was painful, slow, and much less precise than modern tattoos. Many of their designs come from stencils—some of which are 500 years old. Tattoos have long served as a way to commemorate a pilgrimage. It was a way of proving to the world what you had experienced. Pilgrims tend to prefer tradition designs. Young Christians in Jerusalem gravitate toward modern versions of iconography with bold colors. Tattoos are extremely common among Christians where they are a minority. In Egypt, Coptic Christians often tattoo their children with small crosses.

2Solomon Islands

Archaeologists in the Solomon Islands have unearthed obsidian tools used for tattooing 3,000 years ago. The black, glass-like volcanic rock contained traces of charcoal, ochre, blood, and fat. What’s more, researchers were able to replicate tattoos on pigskin using these simple tools. An alternative theory proposes the obsidian tools were used for bloodletting. However, this does not explain the presence of pigments like ochre and charcoal. The Solomon Islands are a vast chain that cuts through both the Melanesian and Polynesian areas of tattoo influence. The islands have at least three different traditional tattooing techniques. Sometimes, ink was applied into cuts. Other times, the ink was applied first and sliced into the skin. In other cases, pigment was applied at the end of a sharp tool. Thorns, fish spines, and bones could all be used to puncture the skin. Obsidian, quartz, and bamboo were used to cut or make incisions.

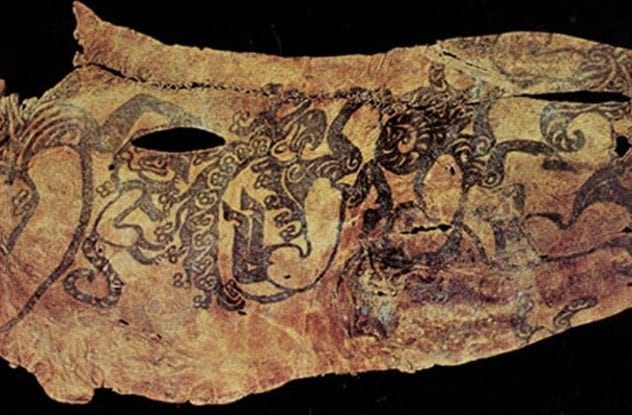

1Pazyryk Mummies

In 1993, archaeologists unearthed an Iron Age grave the Altai Mountains of Siberia. The burial contained mummified Pazyryk tribesmen. The Pazyryk were nomadic herders who used tattoos as a social identifier. The mummies and their markings were in a remarkable state of preservation. Water seeped into the subterranean chamber and froze into a solid block of ice. Along with the mummies, researchers discovered Chinese silk, carpets, and a sack of cannabis in the graves. One of the mummies is believed to be a chief. Aged around 50, the man is covered with intricate designs of intertwined beasts. Along with familiar creatures, there are unidentified carnivores and monsters. The man also has a series of circular tattoos on his neck. These may have had therapeutic purpose. A female mummy dubbed “Princess Ukok” is also cloaked in similar tattoos. Her head is shaved, but she wears a wig and headdress. Abraham Rinquist is the executive director of the Winooski, Vermont, branch of the Helen Hartness Flanders Folklore Society. He is the coauthor of Codex Exotica and Song-Catcher: The Adventures of Blackwater Jukebox.