10 Marie Antoinette’s Missing Son

For about 200 years, no one could say what happened to the son of Marie Antoinette, queen of France. The eight-year-old uncrowned king was called Louis XVII. He was locked up in the Temple prison in Paris during the French Revolution, an event that resulted in both of parents losing their heads to the guillotine. Two years later, legend has it that he was reportedly smuggled from the prison. A deceased body of a lookalike was put in his place. Since prison conditions were harrowing and he was also being physically abused, there was no surprise when the news of the prince’s death reached the public on June 8, 1795. Nearly 100 people have since come forward claiming to be the missing king and rightful ruler of France, but their stories were tabled when DNA tests in 2000 performed on a preserved heart unmasked them as pretenders. The organ came from the child who had died in the prison, kept as a macabre souvenir by the doctor who performed the autopsy. When compared to genetic material grafted from locks of Marie Antoinette’s hair, the heart was a match. This disproved the popular story about little Louis escaping with the help of staff who took pity on him. The child king tragically succumbed in prison, fatally sick with tuberculosis, alone and nameless for two centuries. The heart was buried with full royal honors near his parents’ grave. More than 2,000 people, including European royalty, attended the funeral.

9 The Pharaoh’s Firstborn Son

Several historians have a name for the pharaoh’s heir who died during the biblical plague that smote Egypt’s firstborns: Amun-her Khepeshef. Going one step farther, respected Egyptologist Kent Weeks now believes that he has found Amun-her in the flesh. Well, in the bones. Weeks was working at a mammoth funerary complex in Egypt when his team made what could be a historic discovery. Like a scene from a movie, they found many burial rooms decorated with artistic scenes and inscriptions depicting the lives of Ramses II and his sons. Ramses is the most nominated pharaoh by biblical scholars for the position of “bad guy” in the book of Exodus. The most telling of the finds were canopic jars bearing the name of Amun-her Khepeshef and possibly his organs. There were also four bodies in a pit near the entrance to the tomb, all male. One of the skeletons was arranged in a royal posture and had a badly broken skull. Facial reconstruction of the murdered 3,000-year-old body showed that he had the trademark pointy features of Ramses II’s family. Amun-her was a military general, and the skull damage is consistent with a mace injury. However, the mystery remains. Is the body the fabled biblical firstborn or one of Ramses II’s other sons? DNA testing isn’t possible at this point in time due to the degraded condition of the tissue. Either way, Amun-her died before his father when he was in his late forties or early fifties.

8 Paul I Of Russia

Russia’s Catherine the Great gave birth to her heir, Paul, in 1754. Since Catherine’s husband, Peter III, was more interested in playing with toy soldiers and his mistress, it’s possible that the infant was the illegitimate bastard of Sergei Saltykov, a military officer who might have been Catherine’s lover. Either way, she wasn’t an affectionate mother. Young Paul’s parents despised each other. The marriage troubles eventually reached a deadly standoff. Paul was only eight years old when Peter III, the man he thought of as his father, was poisoned. This left him convinced in his later years that his mother was plotting to murder him, too. However, while his suspicions about murderous schemes were correct, Paul was focusing on the wrong enemy. Catherine the Great felt her son would make an incompetent tsar, but her way of dealing with it was to groom his son Alexander as her heir instead. Unfortunately for Catherine, a stroke felled her before she could make it official, and Paul took the throne. Catherine’s fears were not unfounded; Paul was indeed a neurotic and useless leader. His death is as much a whodunit as his paternity. He was strangled with a scarf. The mystery surrounds his son, Alexander, who might have been in cahoots with the assassins. The young Grand Duke Alexander had attended a dinner earlier that night with his father, but he had eaten almost nothing and appeared uncomfortable. One of the killers also visited his rooms while the rest of the assassins finished off the tsar.

7 Prince Arthur

In 1486, an English prince was born and named after the fabled King Arthur of Camelot. When the Prince Arthur of Wales was barely 15 years old, he was placed in an arranged marriage with Catharine of Aragon, daughter of Spanish monarchs Isabella and Ferdinand. The union, meant to strengthen the alliance between Spain and England, didn’t last long. Five months after the wedding, Prince Arthur died from a “sweating sickness,” a mystery affliction that hasn’t been solved to this day. The teenager, who’d been frail for most of his short life, lived with his new bride at Ludlow Castle near the Welsh border. Their home was inexplicably far away from the prince’s London doctors. His wife and several other people in the area also contracted the unknown epidemic, which some theorize to be tuberculosis or more likely a hantavirus. Catherine survived. In 2002, archaeologists found Arthur’s tomb under the limestone floor of Worcester Cathedral and hope to one day use non-invasive techniques to determine what killed the heir to the throne. His widow married Arthur’s younger brother, who eventually became Henry VIII. She was one of the few wives to survive his nasty spouse-killing habit.

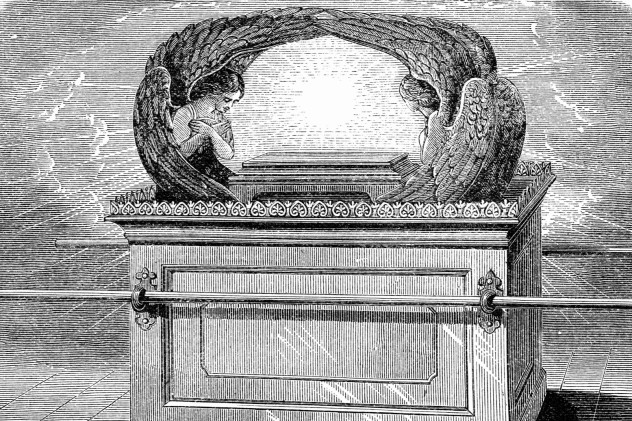

6 Menelik

Menelik was the son King Solomon fathered with the Queen of Sheba. If the Ethiopians are to be believed, he’s also the reason why no tourist today can have his or her photo taken with the Ark of the Covenant. The founding myth for Ethiopia tells how Menelik was raised by his mother in her kingdom but as a grown man eventually met with his father in Jerusalem. When Solomon offered Menelik the opportunity to become his officially recognized heir and rule after his death, the grateful royal offspring decided to make off with the Ark of the Covenant instead. Despite the fact that the Queen of Sheba is mentioned in both the Bible and the Quran, her existence—let alone her son’s—remains largely unproven. Menelik is said to have learned his father’s religion and brought Judaism to his people, a religion still practiced in Ethiopia today. What remains an interesting mystery to most is serious business for one monk in Aksum, where the Ark of the Covenant allegedly remains under his lifelong protection in the holiest sanctuary of Ethiopia. Thousands of years prevent anyone from finding or publishing proof of King Menelik’s life, but for someone who maybe never existed, he had a remarkable influence on one country’s identity, history, and religion.

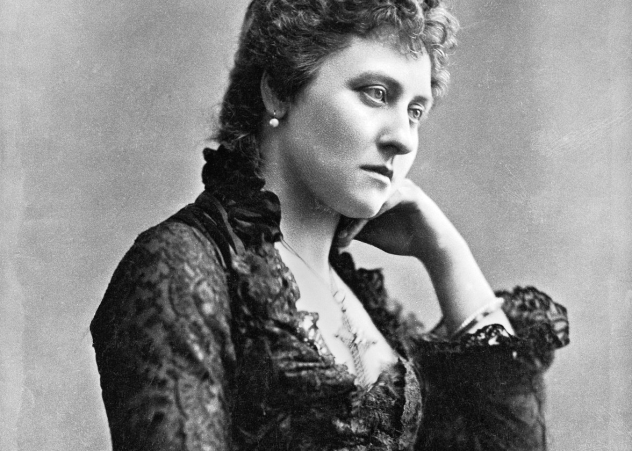

5 Victoria’s Secret Grandchild

While it’s never been proven, a persistent rumor surrounds one of Queen Victoria’s daughters, Princess Louise. Historical notes on Louise are known for describing her beauty, rebellious disposition, and rumored love affairs. Biographer Lucinda Hawksley believes that the princess had an illegitimate son with one of the servants, a man called Walter Stirling. Stirling was the private tutor of Louise’s younger brother, and his dismissal after only four months on the job and subsequent treatment by the royal family was not exactly standard. Stirling never worked for them again, but he continued to be paid an allowance. The baby was purportedly a boy called Henry, born in 1866 or 1867 when Louise was in her late teens. He was given no birth certificate and was quickly adopted by another royal staff member, Sir Frederick Locock, Queen Victoria’s gynecologist. While no one has yet proven whether or not the story is real, the descendants of Sir Frederick Locock and his family sure are. The Locock family has been lobbying for DNA tests since 2004—without success.

4 The House Of Royal Children

In the mid-19th century, Henry Rhind, a Scottish Egyptologist, was excavating at Thebes when he found an ancient mass burial. The bodies all belonged to Egyptian princesses. Not a lot is known about them, and an inscription that gives them the collective title of the “House of Royal Children” opens a mystery that might not be solved for a long time. Nobody is really sure what sort of institution the House of Royal Children was—only that it was populated by palace women and girls of royal blood and that something wiped them out. Many of the names recorded in the tomb are recognizable, such as Tiaa, the sister of Pharaoh Amenhotep III who most likely ruled the mysterious female-only residence. Other familiar names paint a picture of three generations living together, and there is a big chance that they also died together. For so many princesses from one pharaoh’s reign to be buried in the same place hints that they were interred as a group and not individually over a period of time. Inscriptions mention the deaths of an embalmer and possibly some of the women’s servants during the same time. If the reason was some sort of infectious disease, it is likely that the House of Royal Children was physically demolished to prevent its spread—at the cost of an interesting piece Egyptian culture.

3 Saint Dmitry

When it comes to the crown princes of Russia, two of them always steal the show. The hemophilic Alexei Romanov was murdered by the Bolsheviks in 1918. The equally unfortunate Ivan was murdered by his own father, Tsar Ivan the Terrible. Shortly after the tsar fatally clobbered his son, his wife gave birth to another boy. When the infant Dmitry was two years old, his father died. Dmitry’s older half brother ascended the throne and became Tsar Feodor I. At the same time, the toddler was exiled to the small town of Uglich. The sickly Tsar Feodor I wasn’t expected to produce an heir, so Dmitry became the Tsarevich. But in 1591, the nine-year-old crown prince met his end under mysterious circumstances. Officially, he had a knife in his hand, suffered a seizure, and stabbed himself in the neck by accident. Considering the dangerous political environment he lived in and an official death investigation full of irregularities, it’s equally plausible that he was knocked out by an ambitious throne seeker. One legend holds that he was killed on the orders of Boris Godunov, who eventually became the tsar. Dmitry’s mother also accused Godunov of the killing. The boy’s death will probably never be solved, but despite his short life, he is not forgotten. In 1606, 15 years after his death, Dmitry was declared a saint by the Russian Orthodox Church.

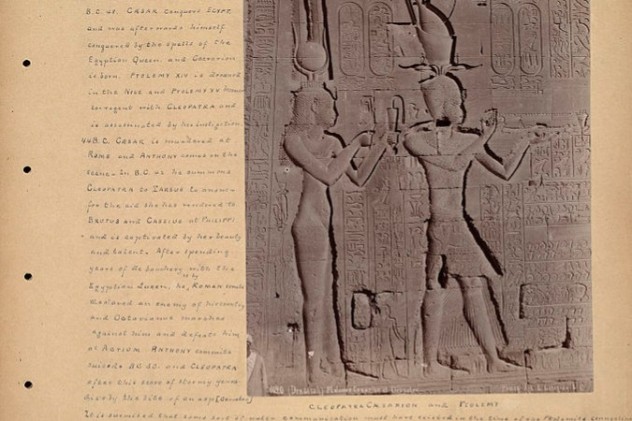

2 Little Caesar

The son of Julius Caesar and Cleopatra only lived for 17 years—officially. He was born in the year 47 BC, three years before Caesar’s murder. During that time, the toddler ruled over Egypt together with Cleopatra. Depending on the source, the little pharaoh may or may not have been acknowledged by Caesar as his son. Caesarion, or “Litte Caesar” as he was sometimes called, was the king of Egypt, but for some mysterious reason, his name was smudged from all official documents after he turned 10. One theory is that Cleopatra wanted to continue her dynasty through the twins she later bore with Marc Antony, but this remains unproven. When Caesarion was a teenager, he became a pawn in a deadly power struggle between Marc Antony and a nephew of Julius Caesar, Octavian. Marc Antony and Octavian shared the rule of Rome, but each wanted full power. Antony tried to tout the boy as the more worthy to rule as Caesar’s supposed son, which no doubt made Octavian determined to kill the young pharaoh. Tensions came to a climax, and when Octavian crushed Antony’s army, which was financed by Cleopatra, both she and Antony committed suicide. Her son had already fled Egypt, and what happened next is hazy. Stories differ. Caesarion may have been murdered on his way to Ethiopia. He could have been strangled after he was lured back to Egypt by the Romans. Maybe he escaped. His body was never found. Whatever the case, the young king was gone when Octavian became the sole ruler of Egypt and Rome.

1 The Missing Romanovs

One of the most intriguing royal puzzles was always that of Anastasia, one of two Romanov siblings missing from the mass grave that contained their slaughtered family’s remains. In 2007, another grave was unearthed about 70 meters (230 ft) from the first. The find was shocking. It revealed the brutalized remains of two murdered children. One was a boy in his early teens and the other a girl between the ages of 17 and 24. Forty-four bone fragments and some teeth were recovered, all badly burnt and shattered. Due to the close proximity to the grave site of the tsar and his family, tests were performed to see if the skeletons were the two imperial children who had never been found. Three different genetic tests were used to reach absolute certainty. When those results came back, they ended one of the world’s greatest mysteries and the claims of Anastasia pretenders everywhere. They were the missing Tsarevich Alexei Romanov and one of his sisters. But questions still remain. Why they were buried in a separate grave cannot be explained, and then there’s the elusive identity of the sister found with Alexei. Was it Maria or Anastasia? Anthropologists don’t agree. One thing is certain though: All the bodies of the Romanov girls are now accounted for, which means that Anastasia didn’t survive her family’s execution in 1918. Whichever grave was hers, she died on the same terrible night that brought an end to the 304-year-old Romanov dynasty. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages