10The Talking Mouse Mystery

Stuart Little, the talking mouse created by E.B. White for a children’s book that was later adapted into a movie, helped to solve the mystery of a Hungarian masterpiece that had been missing for over 80 years in the real world. The Robert Bereny avant-garde work is called Sleeping Lady with Black Vase. A black-and-white photo from a 1928 exhibition was the most recent public evidence of its existence. The painting simply disappeared in the 1920s, but no one seemed to know what happened to it. Then around Christmas in 2009, Gergely Barki, a researcher at the Hungarian National Gallery in Budapest, decided to watch the 1999 film Stuart Little with his young daughter, Lola. To his surprise, the missing painting was a prop hanging over the mantelpiece in the family home of the fictional Littles. “I couldn’t believe my eyes when I saw Bereny’s long-lost masterpiece on the wall behind [actor] Hugh Laurie. I nearly dropped Lola from my lap,” Barki said. “A researcher can never take his eyes off the job, even when watching Christmas movies at home.” But how did such a valuable painting end up as a prop in a Hollywood children’s movie? To find out, Barki fired off a string of emails to people working at Columbia Pictures and Sony Pictures. Two years later, a former assistant set designer for Sony Pictures emailed him with the answer. She had purchased the masterpiece for a mere $500 in a Pasadena, California antiques shop to decorate the Littles’ living room on the movie set. When filming ended, the designer took the painting home and hung it on her apartment wall. After the woman sold Bereny’s masterpiece to a private collector, the painting was returned to Hungary, where it was auctioned in Budapest for €229,500 ($285,700) in 2014. Barki believes the buyer from the 1928 exhibition may have been Jewish and left Hungary with the masterpiece around the time of World War II.

9The Altarpiece Mystery

The key to one of the art world’s greatest mysteries was held by Jean Preston, an elderly pensioner in Oxford, England, who always ate frozen dinners, bought her clothes from a catalog, and traveled only on foot or by bus. For a woman who possessed a fortune in missing masterpieces, she led a poetically austere life—almost as though she were emulating the modest values of Renaissance master painter and Dominican friar Fra Angelico (the “Angelic One”)—by understanding that the true worth of his paintings was in their spiritual beauty and not in the worldly coin they could bring her. The humble Fra Angelico was beatified in 1982 by Pope John Paul II. His most admired work, the San Marco altarpiece in Florence, was commissioned by patron Cosimo de Medici in 1438. The main panel of the altarpiece, depicting the Madonna and child, still resides at San Marco. But the eight smaller panels, portraits of saints, were originally lost during the Napoleonic wars. Six of them were later known to be in galleries and private collections throughout the world. But the last two had been missing for 200 years until they were discovered behind the door of Miss Preston’s spare bedroom. Miss Preston had first spotted the masterpieces in a “box of odds and ends” when she was working in a museum in California. No one else was interested. But she liked them and mentioned them to her art collector father, who purchased the pair for $200. When he died, Miss Preston inherited them. Throughout most of her life, Miss Preston didn’t know the monetary value of the paintings. But in 2005, she asked art historian Michael Liversidge to look at them. When she learned that she had the missing panels of the San Marco altarpiece, she simply hung them back behind the door of her spare bedroom. “She was very pleased but did not express astonishment,” Liversidge said. “As a medievalist, she was interested in them for their academic content—not remotely for their cash value.” Her nephew, Martin Preston, echoed the sentiment. “She was not interested in money, but in the artistic worth of things.” After her death, the two paintings were sold at auction in 2007 for approximately $3.9 million.

8The Sloppy Restoration Mystery

When they were neighbors in Vermont in 1960, Donald Trachte, the illustrator of the Henry comic strip, bought a painting for $900 from Norman Rockwell. Called Breaking Home Ties, the painting had been featured on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post in 1954. After Trachte died in 2005 at age 89, his family and art experts couldn’t understand why the painting in Trachte’s home had so many differences from the version on the Post cover. For example, the boy’s face and the coloration appeared to be inconsistent with the cover version. At first, the experts assumed the painting had been preserved poorly and restored in a sloppy manner. But eventually, they realized the painting hadn’t been restored at all. Convinced they were dealing with a fake, Trachte’s grown sons began to scour their father’s studio for clues. One of the men spotted a gap in the room’s wood paneling. They pulled out the fake wall and discovered a hidden room housing the genuine Rockwell painting. It’s now believed that Trachte forged the painting around 1973 during a bitter divorce. Although the painting remained hidden, he was awarded the Rockwell in the divorce settlement. The original painting was sold at auction for $15.4 million in 2006, the most ever for a Norman Rockwell at that time.

7The Lombardy Mystery

This masterpiece had been missing for so long that some people doubted its existence. Then, in 2013, the Leonardo da Vinci painting of Isabella d’Este, Marquesa of Mantua, was discovered in a private collection inside a Swiss bank vault, and a 500-year-old mystery appeared to be solved. It’s believed the painting was purchased by the owner’s family around the early 1900s. Da Vinci drew a pencil sketch of d’Este in 1499 in Mantua, located in the Lombardy region of Italy. That pencil sketch hangs in the Louvre Museum in France today. The marquesa wrote to da Vinci to ask for a painting from the sketch. Until recently, art experts assumed he never found the time to complete the painting or simply lost interest in it. Some experts like Martin Kemp of Trinity College, Oxford doubt the painting’s authenticity. “Canvas was not used by Leonardo or anyone in his production line,” Kemp said. “Although with Leonardo, the one thing I have learned is never to be surprised.” But other experts like the world’s leading da Vinci scholar, Carlo Pedretti of the University of California, Los Angeles, disagree with Kemp. “There are no doubts that the portrait is the work of Leonardo,” he said. Pedretti believes da Vinci painted the face, and da Vinci’s assistants painted a palm leaf held by d’Este in the painting. Carbon dating suggests a 95-percent probability that the painting was created between 1460 and 1650. The pigments and primer are the same as the ones used by da Vinci. Also, da Vinci is believed to have met d’Este at the Vatican in 1514. Some experts think he may have completed the painting there. But one clue suggests that da Vinci did finish his masterpiece. While visiting France in 1517, he showed some of his work to Cardinal Luigi d’Aragona. The cardinal’s assistant wrote: “There was a painting in oil depicting a certain Lombardy lady.” With no more than 20 authentic da Vinci works in existence, this painting may be worth tens of millions of dollars.

6The Autoworker’s Kitchen Mystery

In 1975, two stolen masterpieces were purchased for $25 by an unwitting Italian autoworker at an auction of items from the Italian national railway’s lost and found department. The paintings were The Girl With Two Chairs by Pierre Bonnard and Still Life of Fruit on a Table with a Small Dog by Paul Gauguin. They had been stolen from a British couple in 1970. Together, they were valued at $50 million. The autoworker had no idea how valuable the paintings were. He simply hung them in his kitchen for almost 40 years. When his son tried to sell the masterpieces in 2013, art experts who were examining them realized they were stolen works. The police were alerted, but the man and his son were not under suspicion. The British couple who originally owned the paintings had already died without heirs. So the legal system now has to determine who owns the paintings.

5The Garbage Bag Mystery

As Elizabeth Gibson walked to get coffee one morning in March 2003, she saw a colorful abstract painting sandwiched between two large garbage bags in front of a Manhattan apartment building. She felt the painting was powerful but never suspected it was a masterpiece, especially with its cheap frame. But the painting she rescued from the garbage that day was Three People, a 1970 work by Mexican artist Rufino Tamayo. It had been stolen in the 1980s from the true owners, a married couple in Houston. Ms. Gibson hung the painting in her apartment. Eventually, she examined the painting and noted gallery stickers on the back. Although she tried to find more information, it wasn’t until three years after she first spotted Three People that someone in a gallery informed her that it was a “famously stolen” painting. Ms. Gibson did a Google search, found a reference to an Antiques Roadshow TV episode and went to Baltimore to view a rerun of the “Missing Masterpieces” segment featuring Tamayo’s painting. When she returned to New York, she went to see the expert from Sotheby’s who had appeared on the show to talk about Three People. At first, she identified herself only as “Mystery Woman.” But she eventually let the expert see the painting in her apartment. He confirmed it was the missing masterpiece and gave her a $15,000 reward from the original owners and a finder’s fee from Sotheby’s. The painting, also known as Tres Personajes, was sold at auction by Sotheby’s for over $1 million in November 2007.

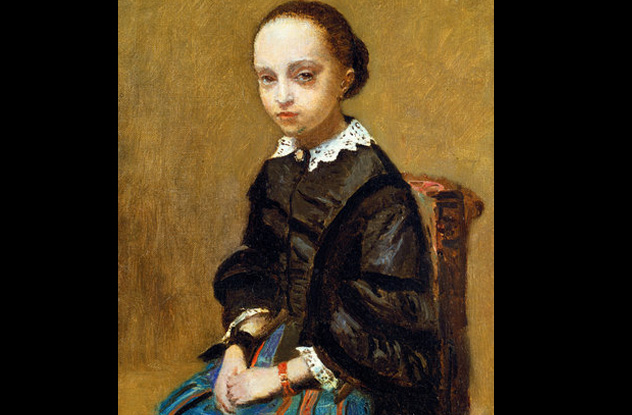

4The Drunken Middleman Mystery

At first, no one else in this strange tale may have known that Thomas Doyle was a felon with 11 previous theft convictions over 34 years. This time, he convinced investor Gary Fitzgerald to pay $880,000 for a supposed 80-percent share of the oil painting Portrait of a Girl by 19th-century French artist Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot. Doyle had paid just $775,000 for the masterpiece, not $1.1 million as he told Fitzgerald. Doyle also told Fitzgerald that another buyer was ready to snap up the painting for $1.7 million. Again, not true. In fact, Doyle allegedly knew the painting had been appraised at not more than $700,000. Now the strange part happens. Doyle’s alleged girlfriend, Kristyn Trudgeon, was supposedly the real majority owner of the painting, with Doyle as her co-owner. She also supposedly didn’t know of his criminal background. On July 28, 2010, the two partners sent one of Doyle’s associates as a middleman sales agent to meet with a potential buyer for the painting at a Manhattan hotel. The buyer didn’t want it. The middleman got drunk and was later seen stumbling out of the hotel at about 12:50 AM with the painting. But he arrived at his apartment around 2:30 AM without the Corot masterpiece. The middleman claimed he lost the painting, so Trudgeon (Doyle’s girlfriend and co-owner) sued the middleman. Then Doyle was arrested on wire fraud and mail fraud charges for swindling Fitzgerald (the man who paid him $880,000 for 80 percent of the painting). The girlfriend saw Doyle’s mug shot, realized she was in league with a felon, and dropped her lawsuit against the middleman. But no one knew where the missing masterpiece was until a doorman at another Manhattan building close to the hotel returned from a vacation. He had found the painting in the bushes. Believing that the work might belong to someone living in his building, he placed the masterpiece in his locker. When he returned from vacation, he learned the painting was missing and gave it to the police. Doyle received a six-year prison sentence, and the Corot masterpiece was sold to make restitution to the swindled investor, Fitzgerald.

3The Flea Market Mystery

As the old saying goes, if it sounds too good to be true, it probably is. So when a Virginia woman claimed to have purchased the napkin-sized Renoir painting On the Shore of the Seine for $7 in 2009 at a flea market, it seemed improbable. At first, the woman called herself “Renoir Girl” as she tried to sell the painting through an auction house. But she was later identified as Marcia “Martha” Fuqua, and the painting was found to have been stolen from the Baltimore Museum of Art in 1951. The woman’s brother, Matt Fuqua, disputed her story. Their mother, Marcia, had gone to art college in Baltimore when the painting went missing in 1951. Matt thought the painting had been a gift to his mother years earlier from a suitor, but she had never revealed the details. Matt said the painting had hung in his mother’s home for years. Other family friends and acquaintances confirmed this. In early 2014, a judge returned the painting to the museum. The judge didn’t comment on the veracity of Renoir Girl’s story. But Matt Fuqua was happy with the outcome. He claimed that, before her death, his mother had told Martha to return the Renoir to the museum. “My mother wanted this,” Matt said.

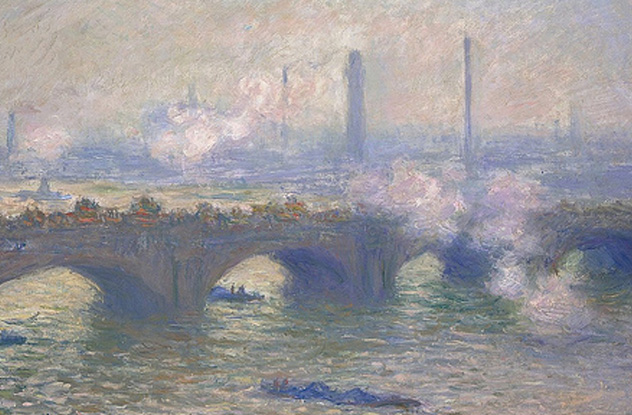

2The Oven Mystery

Part of the mystery of these missing masterpieces has been solved; part may never be solved. In October 2012, seven paintings worth tens of millions of dollars were stolen from the Kunsthal museum in Rotterdam. They included works by Meyer de Haan, Lucian Freud, Paul Gauguin, Henri Matisse, Claude Monet, and Pablo Picasso. According to security camera footage, it was a daring raid by two men who disarmed the security system and stole the loot in less than two minutes. Some art dealers suspect that it was a contract job by organized criminals. Nevertheless, the artwork was believed to have been taken to Rotterdam then to a poor village called Carcaliu in Romania, where at least one of the thieves lived. There, the mother of one of the thieves claimed to have burned the artwork in an oven to destroy evidence that could incriminate her son. In court, she recanted that statement. “We found a lot of pigments used in professional oil paints and a large number of these fragments of pigment were attached to canvas primer, which bore the imprint of canvas,” said Ernest Oberlander-Tarnoveanu, director at the museum that analyzed the ashes. “The conclusion is that somebody burned oil paintings in the stove.” At best, the analysis would show that paintings were burned, but not which ones. The three young male Romanian thieves were convicted in court, so we know who stole the missing masterpieces. But we may never know where they are, and if they’ve truly been burned or just hidden away. The oven mother got two years in jail for helping a criminal and breaking the law on guns. A separate court case was to be conducted into her alleged burning of masterpieces.

1The Nonexistent Man Mystery

Cornelius Gurlitt, 81, “was a man who didn’t exist,” according to a German official. He wasn’t registered with any German government agencies, and he didn’t have a pension or health insurance. But he did have a big wad of cash when customs authorities stopped him on a train to Munich. As part of a tax probe, authorities searched his squalid flat in the suburbs of Munich in 2011. Hidden among the junk, they found a collection of more than 1,400 artworks worth over $1.3 billion. Some were masterpieces by Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso, among others. The works included drawings, engravings, paintings, prints, and woodcuts. Much of the art was believed to have been seized by the Nazis. “I think it’s the biggest single find of Holocaust pictures that there’s been for years,” said Julian Radcliffe, chairman of the Art Loss Register. “They were the sort of pictures that the Nazis would have looted, either to sell for hard currency, or in certain cases because they wanted them for their own museums.” An unemployed recluse, Gurlitt occasionally sold some of the art for living expenses. Gurlitt’s father, Hildebrand Gurlitt, had been an art collector when the Nazis came to power. Even though he had a Jewish grandmother, Hildebrand was valuable to the Nazis because he had the contacts to sell art to foreign buyers. However, Hildebrand sold some of the pieces secretly and stashed the others, while claiming that these masterpieces were destroyed when his flat was bombed during the war. Another collection of over 200 items was discovered at Cornelius Gurlitt’s Salzburg home. According to his lawyer, Cornelius Gurlitt has told his legal team to return any looted works to their Jewish owners.