Each era of US manufacturing creates new industrial hazards. Prior to the advent of nuclear power and large chemical manufacturing, the largest industrial disasters in the US tended to be caused by the technology of the times. In the 1800’s, this included the advent of early high explosives like nitroglycerin, the beginning of steam power and thus boiler explosions, and the push to make factory buildings ever larger which led to collapses. In the early 1900’s, there came the danger posed by the mass production of arms for war, and the advent of manufacturing and storage of brand new (and dangerous) chemicals. The cutoff date I used for my first list of American industrial disasters was post WWII. This list will focus on disasters that took place in America from the end of WWII (1946) and earlier. Unfortunately, there is no shortage of them. So here are ten of the worst industrial disasters in the USA before WWII.

On February 4, 1850, just after work had begun for the day at 8:20 AM, an explosion rocked the press room and machine shops of A. B. Taylor & Co., hat manufacturing building on Hague Street, New York City. The boiler in the press room and machine shop had exploded. Over one hundred people employed by Taylor & Co. hatters were at work. Witnesses claimed the explosion lifted the building off its foundation and it collapsed into a pile of rubble, trapping those inside. Firemen responding to the scene had to dig to try to find survivors, including many young boys. One boy was buried in the rubble for 33 hours before finally being rescued, but he died a short time later. In total, sixty-three people were killed, while about seventy were injured. The cause of the explosion was attributed to the boilers – which were still relatively new pieces of equipment in 1850, and prone to disastrous explosions. The owners claimed it was a new boiler but others stated the boiler was an old one, taken from a ship and patched together.

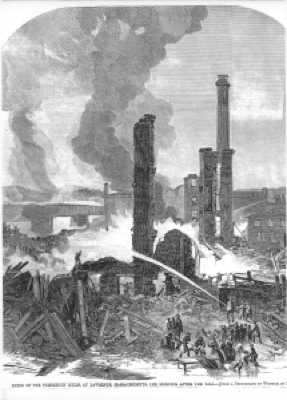

The Pemberton Mill was a large factory in Lawrence, Massachusetts, which collapsed without warning on January 10, 1860, in what was one of the worst industrial calamities in American history. An estimated 145 workers were killed, and 166 injured. The Pemberton Mill, built in 1853, was a five story building, 280 feet long and 84 feet wide. The original owners sold the mill, and the new owners jammed more machinery into their factory, attempting to boost its profits. Shortly before 5:00 p.m. on a Tuesday afternoon, workers in nearby factories watched with horror as the Pemberton Mill buckled, and then collapsed, with a mighty crash. Owner George Howe escaped as the structure was falling. Dozens were killed instantly, and more than six hundred workers, many of them women and children, were trapped in the twisted ruins. When the winter sun set, rescuers built bonfires to illuminate their efforts, revealing “faces crushed beyond recognition, open wounds in which the bones showed through a paste of dried blood, brick dust and shredded clothing.” Around 9:30 p.m., with many people still trapped in the twisted wreck of the factory, someone accidentally knocked over an oil lantern. Flames raced across the cotton waste and splintered wood — some of it soaked with oil. One trapped man cut his own throat rather than be consumed by the approaching flames; he was rescued, but died from his other injuries. As the flames spread, and now the terror of fire threatened those waiting to be saved. One trapped worker, Mary Bannon, handed her pay envelope to a friend and asked that it get to her father. ‘Bid him goodbye for me,’ she said, ‘You will be saved; I will not’. Rescuers, physicians, families of the trapped victims and spectators were all driven back by the fire. The screams coming from the ruins were soon silenced, leaving rescuers to eventually discover only the burned, smoldering remains of “brick, mortar and human bones … indiscriminately mingled”. The collapse of the Pemberton Mill was determined to have been caused by a number of preventable factors, including the deliberate ignoring of safe load limits, adding extra heavy machinery into the already crowded upper floors of the factory, and substandard construction. The mill was rebuilt and still stands today.

Nitroglycerine was invented in 1846, by Ascanio Sobrero. Before the invention of dynamite by Albert Nobel, it was one of the primary explosives used for excavation and mining activities. Nitroglycerine is also highly unstable and reactive, and can explode with minor changes in heat or pressure, and even the slightest shock. Prior to 1867, nitroglycerine was shipped in liquid (not solid) form. This lead to one of the greatest industrial accidents of early California. In April 16, 1866, three crates of nitroglycerin were shipped to California for the Central Pacific Railroad. They wished to experiment with its blasting capability, to speed the construction of the 1,659-foot Summit Tunnel through the Sierra Nevada, for the building of the Transcontinental Railroad. The crates exploded, destroying a Wells Fargo office in San Francisco, and killing 15 people. The force of the explosion destroyed an area of 40 to 50 feet, including most of the Wells Fargo office and surrounding businesses. Windows were blown out as far as half a mile from the blast. For up to a quarter of a mile away, people thought they were experiencing an earthquake. The crates containing the liquid nitroglycerine had somehow made it across the Pacific Ocean to arrive at the docks of San Francisco. Someone noticed the crates were leaking. The crates were labeled as “general merchandise” and there was no notice that the crates contained such a powerful explosive. The crates were sent to the Wells Fargo Office, and put into the back storage room with other unclaimed freight. Soon, two unfortunate freight clerks went to examine the leaking and unclaimed package. When last seen, they were standing near the crates holding tools, ready to open it. No doubt the vibration of opening one of the crates with hammers or crowbars detonated the nitroglycerine. Fragments of human remains were found scattered in many places. A piece of human vertebrae was blown over the buildings on the east side of Montgomery Street, where it was picked up on Leidsdorff street. A human arm struck the third story window of the building across the street. This tragedy lead to a complete ban on the transport of liquid nitroglycerin in California. The on-site manufacture of nitroglycerin was thus required for the remaining hard-rock drilling and blasting, required for the completion of America’s First Transcontinental Railroad. A newspaper description of the tragic event stated: “This must be stopped at once … There must be a total discontinuance of the practice of carrying suspect packages under the term ‘merchandise.’ Public safety demands it.” Unfortunately, as the people aboard ValuJet Flight 592 found out on May 11, 1996, dangerous materials can still be shipped without proper labeling of their hazardous contents, and still result in tragedy.

As we learned from the previous list of American Industrial Disasters (Imperial Sugar Refinery explosion of 2008)– organic dust of any type can become explosive under the right conditions. On May 2, 1878: The Washburn “A” Mill in Minneapolis was destroyed by a flour dust explosion, killing 18 people. The mill was rebuilt with updated technology and the explosion led to new safety standards in the milling industry. The first Washburn A Mill, built by C. C. Washburn, in 1874, was declared the largest flour mill in the world upon its completion. On May 2, 1878, a spark ignited airborne flour dust within the mill, creating an explosion that demolished the Washburn A, and killed 14 workers instantly. The ensuing fire resulted in the deaths of four more people, destroyed five other mills, and reduced Minneapolis’s milling capacity by one third. Known as the Great Mill Disaster, the explosion made national news and served as a focal point that led to reforms in the milling industry. In order to prevent the buildup of combustible flour dust, ventilation systems and other precautionary devices were installed in mills throughout the country. By 1880, a new Washburn A Mill opened as the largest flour mill in the world. At the peak of the Washburn A Mill’s production, it could grind over 100 boxcars of wheat into almost 2,000,000 pounds of flour per day.

– 1905

It’s hard to believe today, but at one time shoe manufacturing was a major business in the United States. New England was an especially productive area of the country for shoe manufacturing. One of the largest shoe manufacturers was the R. B. Grover shoe factory, located in Brockton Massachusetts, a town that employed about 35,000 shoe workers, at the time. The Grover Shoe Factory was a wooden building, shaped like a letter E, that occupied half a city block. Business had been good enough of late that Grover decided to add a fourth floor to the building to increase production. At the time, most industrial facilities had large coal-fired steel boilers installed in brick boiler houses, which were usually attached to the factory. These huge boilers fed steam to radiators which heated the plant. At the Grover plant, when the fourth floor was added, the original boiler was replaced by a larger one, and the old boiler, 17 feet long and six feet in diameter, was left in place as a backup. Since the new boiler could generally meet the factory’s demands on its own, the old one was seldom used; and when used, was used reluctantly. Reluctantly because the Grover plant engineer did not trust it. The new boiler had to be flushed out as part of its regular maintenance, so the old boiler was put back into service, temporarily. On that cold damp Monday, before day shift workers arrived, the engineer and his boiler plant workers fed coal into the old boiler and fired it up. At 7:45 a.m. the plant manager noticed strange noises coming from the radiators along one wall. He called the plant engineer who assured him everything was fine. A few minutes later, on March 20, 1905, the old boiler exploded, rocketing up through three floors and the roof. The flying boiler knocked over an elevated water tower at one end of the building, and its full tank smashed through the roof, causing one end of the building to immediately collapse. The floors pancaked down and the walls fell in on the workers inside the building. Many workers who survived the initial explosion and collapse were trapped by broken beams and heavy machinery. To make matters worse – burning coals thrown from the boiler’s fire pit landed throughout the debris, starting fires that were fed by broken natural gas lines. The factory’s more than 300 windows, now blown out, created a chimney effect in the parts of the factory still standing, resulting in a fire hot enough to melt iron pipes and radiators. The wooden floors, treated nightly with linseed oil to keep the dust down, burned quickly. Firefighters and local citizens were able to lift some of the wreckage and rescue some workers before the flames reached them. But, when it seemed the disaster could get no worse, barrels of highly volatile naphtha, stored in a wooden shed directly behind the boiler house, exploded, throwing sheets of flame onto the wreckage and driving rescuers away. Between 300 and 400 workers were in the factory at the time of the explosion. Workers in the sections still standing escaped down stairways or climbed to the roof; others had to jump from windows because the explosion had knocked some fire escapes off the building. About 100 workers escaped unharmed, and 150 were injured. But 58 workers were killed. Due to the extreme heat of the fire, only a few bodies could be positively identified. Police later related the story of a worker so dazed that he left the scene, applied for a job at another shoe factory, worked all day, then went home to find his family mourning him. The plant engineer was among the dead. What caused the old boiler to explode was never proven. It appears it simply failed under the repeated stress of years of operation. Engineers estimated the force of the boiler explosion as equal to 660 pounds of dynamite. By 1890, some 100,000 boilers were in service throughout the USA, with over 2000 boiler explosions since 1880. Boiler inspections were rare, and operating guidelines almost nonexistent. The Grover disaster brought new cries for improved industrial safety. A Board of Boiler Rules was formed, drafting a simple three-page set of rules. Though they had overcome manufacturer objections to “needless government interference”, (Heard that one recently in the US? The more things change the more they remain the same don’t they?) Massachusetts passed one of the first boiler inspection laws, in 1909. The Massachusetts laws eventually led to passage of a national boiler safety code. Pesky government interference. Always saving lives.

On January 20, 1909, during the construction of a water intake tunnel for the city of Chicago, a fire broke out on a temporary water crib, used to access an intermediate point along the tunnel. Water cribs are offshore structures that collect water from close to the bottom of a lake to supply a pumping station onshore. The temporary water crib was located a mile and a half off shore in Lake Michigan, and was being used to construct a new submarine water tunnel to Chicago. There were about 95 men working on the crib when the fire began, in a dynamite magazine stored in a small out building. This then set fire to the wooden dormitory that housed the tunnel workers. With literally nowhere to run to safety, 46 workers survived the fire by jumping into the lake and climbing onto ice floes on the frozen lake. However, about 60 men died, with 29 men burned beyond recognition. Most of the remaining men drowned or froze to death in the lake, and were not recovered. One of the workmen made his way through the smoke to a telephone that communicated with the shore station. His frantic call awakened the drowsy attendant on shore who heard the following call for help: “The crib is on fire! For God’s sake send help at once or we will be burned alive! The tug” — At this point communication ceased. On shore, through the fog, the flames of the blaze could be seen rising from the water crib. The crew of the tugboat Morford made a heroic effort to save the men and fought through the ice, getting as close to the site of the fire and explosion as they could get. They rescued a few survivors in a boat, and plucked others from the water or the ice floes.

The Morgan Depot Explosion, occurred at 7:30 p.m. on October 4, 1918, at an ammunition plant operated by the T.A. Gillespie Company and located near Sayreville, in Middlesex County, New Jersey. The initial explosion triggered a fire and subsequent series of explosions which continued for three days. The facility, said to be one of the largest in the world at the time, was destroyed, along with more than 300 buildings, forcing reconstruction of South Amboy and Sayreville. According to a 1919 government report, the explosion destroyed enough ammunition to supply the western front for six months. Among many others involved in rescue operations, a number of United States Coast Guardsmen stationed in Perth Amboy, New Jersey, were involved in rescue operations. Twelve of the Coast Guardsmen received Navy Crosses for their heroic actions. Two Coast Guardsmen died in the effort. The award citations indicate that during the conflagration they risked death when they relocated a train loaded with TNT, that was threatened by the fire. Despite these and other heroics, the carnage from the explosion and fires was so complete that martial law was declared following the accident, and the 60,000 residents of Sayreville, South Amboy and Perth Amboy, were evacuated. The death toll for the accident is unknown, because the number of people working inside the plant at the time was lost, when the employment records were destroyed. Over 100 people were probably killed, with hundreds more injured. The unidentified remains of 14 to 18 workers were buried in a mass grave. The disaster occurred at the same time the 1918 influenza epidemic was sweeping the nation. Many survived the explosion and fires, but died due to the epidemic. The explosion was so powerful that debris was scattered around a large area and never recovered. In 2007, unexploded ordnance and other material from the facility was found at an elementary school, while grading an area for a playground.

The Nixon Nitration Works covered about twelve square miles on the Raritan River, near New Brunswick, in what was then unofficially known as Nixon, New Jersey. It was originally created at the outbreak of World War I to supply some of the warring nations of Europe with gun powder. The company manufactured cellulose nitrate, the first plastic, which is highly flammable. The cellulose nitrate was piled in large stacks of sheets in the surrounding buildings. Within the Works, Nixon leased a building to the Ammonite Company. Ammonite was using the facility to salvage the contents of artillery shells for use as agriculture fertilizer. The building reportedly contained one million gallons of ammonium nitrate in storage and fifteen tank cars, each holding 90,000 gallons of ammonium nitrate in the process of crystallization. On Saturday morning, March 1, 1924, at approximately 11:15 AM, the Ammonite building exploded. Windows for a mile around the scene were crashed in, and in many instances doors were blown from their hinges. The blast shook Staten Island, where business buildings rocked, windows rattled and doors were slammed. The explosion was heard as far away as lower New York City and Brooklyn. The flaming debris from the explosion of the Ammonite plant set the highly flammable cellulose nitrate sheets on fire. Fires began to consume other buildings, including the offices of the Nitration Works. Six hours after the explosion, flames were still burning over an area of one square mile. That night, the wind shifted and started pushing the flames toward freight cars and toward the adjacent Raritan Arsenal. In the arsenal were 500,000 high-explosive shells. Exhausted firefighters managed to keep the flames away from the arsenal, preventing an even larger catastrophe. As it was, several square miles around the plant were wiped off the map, as was the small town of Nixon, New Jersey. Twenty people were killed, over one hundred were injured and forty buildings were destroyed. The dead included the wife and three children of an employee of the plant, who lived one hundred yards from the scene. The following year Ammonite pled guilty to charges arising from the explosion and was fined a total of $9,000 (reflecting a $600 fine for each of 15 employees killed in the blast). In 1954, the citizens of Middlesex County’s Raritan Township renamed their community by referendum. The name Edison was chosen over Nixon. However, the Nixon name is still used by the local post office and postal district.

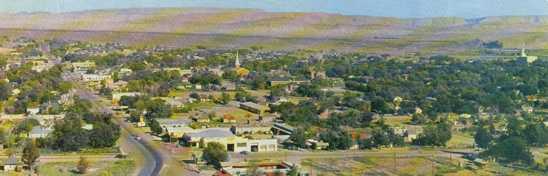

Drilling for oil, whether in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010, or on land in 1935, is dangerous business. One of the most dangerous points in the entire oil drilling process is called “shooting the well”. On January 21, 1865, Col. E.A.L. Roberts made the first successful oil well shot, on the Ladies Well near Oil City, Pennsylvania. This was the spot where, five years earlier on August 27, 1859, Col. Edwin L. Drake completed the first well drilled specifically for oil. Roberts used 8 pounds of black powder (nitroglycerin was not used until 2 years later) to blast open or “shoot” the well. Oil Well Shooting in no small measure saved the fledgling Pennsylvania oil industry. Over time, black powder was replaced by nitroglycerine, dynamite, TNT, and other more powerful, effective (and safer) high explosives. In March of 1935, owners, workers, their families and spectators gathered to watch the first “shoot” of a Utah oil well in the St. George Utah area. One of those looking on was Mr. George Aslop, owner and manager of the Arrowhead Oil Corporation, who was drilling the well, along with his wife. A specialist in shooting wells was brought in for this shoot, and he was lowering a charge of nitroglycerine into the unfinished well when it exploded prematurely, ripping the derrick from its moorings and hurling it onto the crowd surrounding the well. The terrific blast could be felt as far as five miles away. The explosion killed 10 persons and injured at least a dozen others who had gathered to watch the spectacular “shooting”. Scores were thrown to the ground. One man watching from his car survived, but the force of the explosion ripped the roof off his car. Among the victims were George Aslop and his wife, as well as CM Flickenger, who was the “expert” brought in to shoot the well.

The Cleveland East Ohio Gas Explosion occurred on the afternoon of Friday, October 20, 1944. The resulting gas leak, explosion and fires killed 130 people and destroyed a one square mile area on Cleveland, Ohio’s east side. The natural gas storage tank at the East Ohio Gas Co. plant in Cleveland, Ohio, was located north near East 61st and East 62nd Streets. The explosion occurred at 2:40 PM on a Friday afternoon. Fortunately, the explosion occurred when schools were still in session, keeping many children away from the heart of the explosion. To increase storage capacity in the tanks, the gas company had liquefied the gas. Apparently, storage tank #4 sprung a leak along a seam and started to release the liquefied gas. The prevailing winds off Lake Erie forced the vapor towards the city. The gas settled into the sewer system through catch basins and gutters. Mixing in the sewers with sewer gas and oxygen, it created a volatile mixture that a spark must have ignited. The resulting explosion caused manhole covers to fly into the air and created a fireball underground that ignited numerous homes and businesses. One manhole cover was found several miles east, in the Cleveland neighborhood of Glenville. The fireball supposedly was more than three thousand degrees Fahrenheit in temperature. With the country in the midst of World War II, some residents initially suspected a German saboteur. The explosion caused fires and follow up explosions at other storage tanks. Cleveland residents could see the resulting fireballs from at least seven miles away. The force of the explosion broke windows more than one mile away, and rang the bells of a local church. For the people who survived, most lost everything. The flames destroyed several blocks of homes. As a result of the explosions, the East Ohio Gas Co. began to store its natural gas underground, and this became industry practice (to store gas outside city areas and/or below ground). The company also helped rebuild the community by paying more than three million dollars to neighborhood residents, and an additional one-half million dollars to the families of the fifty-five company workers who lost their lives. The final death toll was 131 people killed. Twenty-one of the victims were never identified.

I included this as a bonus on the list because it demonstrates that most industrial accidents or disasters do not kill scores of people, they usually kill just one, or a few. Not that this makes the disaster any less tragic. These accidents seldom make more than local news and are not often recorded for history. I also included it because it took place back in 1912, right here in my hometown of Lancaster, PA. Workers at the Belmont quarry were thawing dynamite to prepare it to be used for blasting quarry rock, when it exploded. The dynamite was stored in a small shed, and Linarolo Pugliez was just entering the shed when the blast occurred. He was killed instantly, and the building was blown to pieces. One other worker was badly injured by flying debris. Fifteen other workmen were nearby, but none was injured. A mule they had with them at the time escaped injury. Unfortunately, Pugliez’s dog was with him, and it was also killed.