Many know about some of the more famous items that were on board. A few were depicted in the 1997 film “Titanic” including the Renault automobile being shipped to the States by its owner, William Carter (he claimed an insurance loss of $5,000 for the car), and expensive paintings that Rose Dawson was carrying with her. Though in the movie the paintings were by French Impressionists, the real painting lost when the ship sank was an oil painting by Blondel, “La Circasienne Au Bain” (insurance claim amount of $100,000). We know the contents of the Titanic shipping manifest because it was delivered aboard the Mauritania (Titanic sister ship). The manifest survived because it had been sent to America via registered mail aboard the other ship. Insurance claims document even more lost items. Here are ten of the lesser-known items that sank with the Titanic that fateful night in April 1912, and some interesting stories of the people associated with these items.

On board the Titanic were three cases of coney skins headed for The Broadway Trust Company of Camden New Jersey. Coney skins was a term used to describe rabbit skins, which were used at the time to line clothing and children’s coats and sacks. The Broadway Trust Company was a bank which operated until shortly after the start of the Great depression, when many small banks closed their doors. The building itself is now on the National Register of Historic Places. One other bit of bad luck was destined to strike The Broadway Trust Company. On October 5, 1920, Broadway Trust’s bank messenger, David S. Paul, mysteriously disappeared while carrying tens of thousands of dollars worth of cash and securities. His body was found on October 16, near Tabernacle in the New Jersey Pine Barrens. He had been kidnapped, murdered and robbed by two acquaintances, Frank J. James and Raymond Schuck, who were tried and convicted of his murder. They were executed in New Jersey’s electric chair, on August 30, 1921.

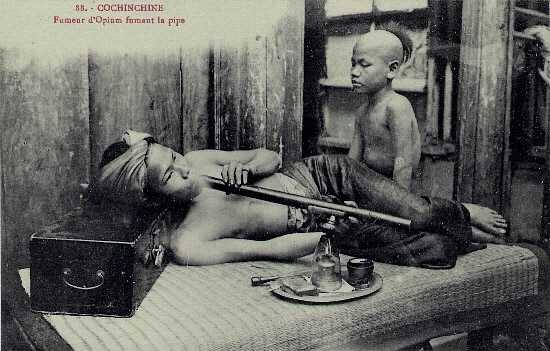

On board the Titanic were four cases of opium. Also aboard the Titanic was John Jacob Astor IV, who was the great-grandson of John Jacob Astor, whose fortune was made in opium, fur trade and real estate. Neither the opium nor Astor would reach New York. Only seven years prior to the sinking of the Titanic, the US Congress had banned opium, but it was still widely used in all manner of medicines and concoctions. A year later, the U.S. Congress passed the Pure Food and Drug Act, requiring contents labeling on patent medicines by pharmaceutical companies. As a result, the availability of opiates significantly declined. In 1909 the first federal drug prohibition was passed by Congress, outlawing the importation of opium. For some reason, the opium was still being shipped to the US in 1912, when the Titanic went down. Two years later in 1914, Congress passed the Harrison Narcotics Act, which tried to curb drug addiction (especially for cocaine and heroin) by requiring doctors, pharmacists and others who prescribed narcotics to register and pay a tax.

Another first-class passenger was Harry Anderson, a New York City stockbroker who was returning to America after a visit to England. He was married and lived in New York City with his wife, who did not make the trip to Europe with him. Apparently he did have company with him however, a pet dog. Anderson survived the sinking, escaping in lifeboat #3. The dog, however, met its fate along with 8 out of 12 of the other dogs reported to have gone down with the Titanic. He later put in an insurance claim in the amount of $50 for the loss of his pet Chow dog.

Mr. Emilio Ilario Giuseppe Portaluppi was an interesting survivor of the sinking of the Titanic. He was a second-class passenger heading for Milford, New Hampshire, after a visit to Italy, the country of his birth. He claims he was awakened by the force of the ship hitting the iceberg and initially thought the ship had docked in New York. He quickly realized something was wrong, put on a life vest, and went to the deck. He claims he slipped or tripped while trying to jump into a lifeboat and plunged into the water. Other accounts claim he jumped into the sea. However he got into the water, he was one of the fortunate four people who were rescued by the only lifeboat to return to search for victims after the Titanic sank. Portaluppi was picked up by lifeboat #14 under the command of Officer Lowe. One account claims Portaluppi clung to a chunk of ice and floated until he was rescued. After he was rescued and arrived back in the USA, he submitted an insurance claim for $3,000 for the loss of a picture of Italian national hero Giuseppe Garibaldi, signed by Garibaldi and presented to Potraluppi’s grandfather. This claim seems almost as fantastical as his surviving on a piece of ice floating in the freezing cold water of the North Atlantic, but who knows.

Not much is known about young second-class passenger Sidney Clarence Stuart Collett. He appears to have been a student of Theology, on his way from England to be with his parents in Port Byron New York. One account has the young theological student taking part in one of the most memorable events just before the sinking. It is said Stuart Collett was assisting the Reverend Mr. Carter in the Sunday evening hymnal and prayer service on the Titanic. This service was held the evening of April 14, 1912, in the second-class dining saloon and was attended by about 100 passengers. The Reverend Carter and Collett led in the singing of ‘There is a Green Hill far away,’ ‘For Those in Peril on the Sea’ and ‘Lead, Kindly Light,’ accompanied by piano. At the close of the event, Reverend Carter noted that the ship was unusually steady and how everyone was looking forward to their arrival in New York. He is reported to have said: “it is the first time that there have been hymns sung on this boat on a Sunday evening, but we trust and pray it won’t be the last.” After the ship hit the iceberg, all that is known is Collett assisted two women to the lifeboats. As the women were about to get into them, Collett explained to the crew that they had been entrusted to his care. Collett was allowed to join them in lifeboat #9 and he was saved. Upon arriving in the US, Collet was said to have met his brother, and the first thing he did was to hand a small Bible to him. Apparently, his brother had given Collett the Bible before he departed for England, saying that Collett should return it the next time they met. He then put in an insurance claim for the amount of $50, for the loss of hand written college lecture notes from a 2-year course.

A farm hand from Ireland making his way as a third-class passenger to New York City, Mr. Eugene Patrick Daly was 29 years-old when he boarded the Titanic at Queenstown, having paid his 7 pounds 15 shillings for the passage. When he boarded, he came with his uilleann (elbow) pipes (a traditional Irish instrument), and played “Erin’s Lament” for his fellow steerage passengers, as the Titanic steamed for the new world. He would later file a claim for $50 for the loss. Decades later, a set of bagpipes, possibly those belonging to Daly, were recovered at the wreck site. As the Titanic was sinking, Daly was one of the fortunate third-class passengers who managed to make their way from the depths of the ship out onto the deck. With him at the time were two women, Maggie Daly and Bertha Mulvihill. He helped them board lifeboat #15 and was left behind on board the soon-to-sink ship. Daly told the story of what happened next, one of the most dramatic moments on board the ship just before it sank: “…an officer pointed a revolver and said if any man tried to get in he would shoot him on the spot. I saw the officer shot two men dead because they tried to get into the boat. Afterwards there was another shot, and I saw the officer himself lying on the deck. They told me he shot himself, but I did not see him.” Daly jumped into the sea with only his heavy jacket keeping him warm enough to survive against the freezing water. Daly somehow managed to make his way to overturned collapsible boat B, from which he was later saved by The Carpathia. He later claimed he always took this same coat with him whenever he traveled, for good luck.

Being from the United States, I was not even sure what marmalade was, let alone a “marmalade machine,” so I did some research to find out. Marmalade is a fruit preserve made from the juice and peel of citrus fruits, boiled with sugar and water. The benchmark citrus fruit for marmalade production in Britain is the “Seville orange” from Spain; it is higher in pectin than sweet oranges. The peel has a distinctive bitter taste, which it imparts to the marmalade. Marmalade can be made from lemons, limes or other fruits. In languages other than English, “marmalade” can mean preserves made with fruit other than citrus. Marmalade is sometimes described as jam containing fruit peel, but manufacturers also produce peel-free marmalade. Marmalade is often eaten on toast for breakfast. So fine, marmalade is what we call “jelly” or “jam” made and then preserved in jars with wax seals. But what is a marmalade machine? And more specifically, what was a 1912 vintage marmalade machine and why was its owner, Miss Edwina Trout, carrying one with her from Europe to America aboard the Titanic? It turns out, a 1912-vintage marmalade machine was a device used to cut and peel the citrus slices into just the right shape, size and texture to make perfect marmalade. Apparently, getting the orange peel slices just right is very important to make marmalade the correct way. The “machine” (more like a “cutter”) looks like a combination of a meat grinder and an antique applesauce maker. Miss Edwina “Winnie” Celia Troutt, was 27 years-old and traveling back to America from a visit to England, where she assisted her sister in giving birth to her child. She was originally set to sail on the Oceanic, but she was transferred to the Titanic because of a coal strike in 1912, that was forcing the White Star line to consolidate and stretch its coal reserve, and necessitated delaying some voyages. She boarded the Titanic at Southampton as a second-class passenger. When the ship hit the iceberg, she left her cabin to investigate and was told of the ship’s fate. She also saw the crew uncovering, and getting ready, the lifeboats. She went back to tell her cabin mates but only found one. She put on her heaviest coat against the cold, and encouraged her roommate to hurry up, at one point tossing the woman’s corset down the isle while telling her this was no time for a corset. Winnie later recalled hearing the ship’s band playing Nearer My God to Thee, in the ship’s last moments. Winnie was in lifeboat #16, waiting for it to be lowered to the sea when a man came up begging her to save his child. Winnie took the child into the boat with her. As the boat was lowered Winnie held in her hands a toothbrush, a Bible and the child. She did not carry with her her marmalade machine. She later filed a claim against White Star Line for her lost marmalade machine, valued at 8s 5d. Winnie was a favorite at Titanic functions and conventions, even until she was in her late 90s. She died on December 3, 1984, in California.

On the Titanic manifest was listed “one case of film” for The New York Motion Picture Company. As was the case with automobiles, electronic equipment and phonographs, motion pictures were just becoming hugely popular in the early 1900s. The New York Motion Picture Company was one of many small filmmakers in the New York area and East Coast of the USA (before the movie industry packed up and moved west to Hollywood). The company was formed in 1909, and was operating up until about 1914. It operated at 42nd Street and Broadway in NYC. It was owned and operated by two men, one of whom, Charles O. Baumann ran several successful early motion picture companies, most notably The Keystone Film Company. The short-lived New York Motion Picture Company released films under the brand names Broncho, (for westerns) Domino (for comedies) and Kay-Bee (for dramas). It is not known which type of early silent film would have been made using the film being shipped to New York aboard the Titanic. Given the events of the sinking of the ship, one would hope it was meant for Kay-Bee, the makers of drama films.

One of the first-class passengers aboard the Titanic was a perfume maker from England by the name of Adolphe Saalfeld. He was chairman of the chemists and distillers Sparks, White, and Co. Ltd. He carried with him a leather bag, in which he had 65 vials of different perfumes. As the perfume trade in New York City and America was booming at the time, he may have been traveling with his perfume samples to try to entice potential buyers, such as New York City department stores and boutiques. He claimed to have been in the Titanic smoking room and saw the iceberg when the ship hit it. He went to his room, but left behind the satchel containing his perfume samples. The satchel and vials sank with the ship and there they remained for 89 years until 2001, when they were discovered by members of an artifact search team. When they brought the satchel to the surface and back onto their ship and opened it, they were overwhelmed with the aroma of lavenders and roses from the Edwardian perfume. Some of the vials had broken, but most were, amazingly, intact. Plans were immediately made to decipher the chemical fingerprint of these long lost fragrances in the hope of reproducing them for sale today, possibly with clever names such a Eau de Disaster. As for Saalfeld, he survived aboard lifeboat #3, and was rescued by The Carpathia.

In the mailroom of the Titanic was a package containing the manuscript of “Karain: A Memory” by noted author Joseph Conrad. “Karain: A Memory” was a precursor to Conrad’s ”Lord Jim.” His third short story, “Karain: A Memory” was written in 1897, and published later that same year. Conrad was sending the manuscript to John Quinn in New York. John Quinn was a second-generation Irish-American corporate lawyer in New York, who for a time, was an important patron of major figures of post-impressionism and literary modernism, and collector, in particular, of original manuscripts. This manuscript would never reach him.

Some other interesting items that went down to the bottom of the Atlantic with the Titanic included 856 rolls linoleum, 1 case cretonne, 1 case auto parts, 41 cases filter paper, 76 cases dragon’s blood (pictured above), 15 cases rabbit hair, 1 barrel earth, 1 case Edison gramophones, and 2 barrels of mercury.