10Demolishing The Whole Of Glasgow

The largest city in Scotland, Glasgow is one of the best places on Earth to experience both Victorian architecture and public drunkenness. Had 20th-century planning officials gotten their way, only one of those would now be true. In 1945, city officials published a report suggesting they demolish the whole of Glasgow. Had they just left it at that, the plan might at least have elicited some support from Glasgow’s Edinburgh rivals. But the Bruce Report didn’t want to get rid of Glasgow so much as render it completely unrecognizable. All the old buildings of the city center would be swept away, along with countless Victorian houses, a handful of slums, and the Glasgow School of Art. In their place would be erected a swath of communist-style concrete blocks circled by an endless motorway. This wasn’t just a harebrained scheme that nobody took seriously. In 1947, the plan was given the official go-ahead. So how come we’re not now living in a world where “Glasgow” is a byword for concrete? For that you can thank Adolf Hitler. With Britain utterly broke after over half a decade of fighting in World War II, the proposal was simply too expensive to be feasible. Two years later, the city quietly ditched the plans, but not before several old sections of Glasgow could be destroyed and replaced with concrete monstrosities.

9Carving Two Highways Through The Heart Of Manhattan

A world of artist’s lofts and rapid gentrification, SoHo in Manhattan is one of New York City’s most renowned districts. The whole area was even declared a protected National Historic Landmark in 1978. Yet it’s only by a miracle there was anything left to protect. In the 1950s, New York came close to bulldozing the whole district and building two expressways over it. Proposed in 1946 and known as LOMEX, the Lower Manhattan Expressway would have connected the Williamsburg Bridge and Manhattan Bridge over the East River, as well as the Holland Tunnel into New Jersey. This coiling tangle of roads would have bulldozed right through the heart of Manhattan before converging above SoHo. If you’re thinking that sounds hideously impractical, you’re right. Construction would have destroyed 14 blocks, wiped out Little Italy and most of SoHo, and involved the forced eviction of nearly 2,000 families and over 800 businesses. Those that were left would have to put up with the constant roar of traffic, not to mention the grim reality of living under a concrete overpass. Like the absurd Glasgow plan above, LOMEX officially got the go-ahead. In 1968, the project was approved by the Federal Bureau of Public Roads. Thankfully, by this point, public support for the project had ebbed. In 1971, Governor Nelson Rockefeller shelved the project indefinitely.

8Filling In Santa Monica Bay

One of California’s most popular stretches of coast, Santa Monica Bay is basically nature’s silver lining to the cloudy fact that you’re living in downtown Los Angeles. The beaches are cool, the surf good, and the marine ecosystem wonderfully diverse. In the 1960s, it was decided the most intelligent thing to do with this little slice of heaven was to fill it with rubble. At the time, the Pacific Coast Highway in the nearby Santa Monica Mountains was constantly clogged with traffic. This was affecting downtown LA’s streets and causing gridlock in Santa Monica itself. Fed up with waiting in traffic, city officials decided to build a new freeway connecting Santa Monica with distant Malibu. With no space to build it on the land, they turned to the ocean. Stretching 10 kilometers (6 mi) and requiring the creation of dozens of artificial islands, the Santa Monica Bay Causeway would cost half of what the entire city was worth. It would also have required leveling a good deal of the nearby mountains and pouring the rubble into the bay, filling it up. The result would have been the destruction of ecosystems, beaches, and one of California’s most beloved views. Thankfully, it also would have been very expensive and perhaps even impossible to maintain. Faced with a multitude of technical challenges, the city eventually abandoned the project.

7Thomas Willson’s Pyramid Of Death

It sounds like something from a creepy sci-fi film. A vast, forbidding pyramid looming 94 floors over a storm-lashed metropolis. Inside, winding catacombs lead through endless chambers of the dead. Bodies upon bodies, stacked high into the heavens. Five million dead, all crammed into this one spooky space. In 19th-century London, this morbid vision nearly became a reality. Proposed by Thomas Willson, the Pyramid of Death would have been 7 square kilometers (2.7 mi2), sitting on top of Primrose Hill as a repository for all of London’s dead. If you’ve ever been to London, you’ll know what a fundamentally insane idea this was. Primrose Hill is one of the most beloved viewing points in the British capital, a stretch of awesome parkland enjoyed by locals and visitors alike. Placing such a megastructure on it would not only have destroyed all that, it’s likely its weight would have literally flattened the hill. Even creepier were Willson’s intentions for the monument. Rather than designing it as a noble work for public good, he hoped to make £10 million in profit from selling spaces for storing London’s deceased. Eventually, the project was nixed because of the damage it would cause to Primrose Hill. Remarkably, taste didn’t come into it, despite the proposed structure later being likened to a “giant car park of the dead.”

6Demolishing Manhattan’s Entire West Side

New York’s a real love-it-or-hate-it city. For every person raving about its vibrant arts scene or gritty street life, there’s another secretly wishing the whole place could just be chucked in the Hudson River. If you’re the latter type, the Hudson River Terminal might sound like a dream come true. In 1946, it was proposed that the whole West Side of Manhattan be demolished and replaced with an impossibly large airport. The project was the brainchild of William Zeckendorf, a real estate mogul responsible for a significant chunk of modern NYC’s urban landscape. In other words, he wasn’t just a nut with an impossible dream. He was a nut with an impossible dream and the means to possibly achieve it. When Life covered his plans in a 1946 issue, it assured readers that increasing air traffic meant the design would eventually become a necessity. If it had been given the go-ahead, the airport would have covered 144 blocks, been roughly the size of Central Park, and handled as many planes an hour in the 1950s as JFK Airport manages today. For reasons of cost and obvious insanity, the Hudson River Terminal was shelved before it ever got off the ground. That wasn’t the end of Zeckendorf’s dreams, though. Around the same time, he tried to build his own private city-within-a-city on the land now occupied by the UN Headquarters.

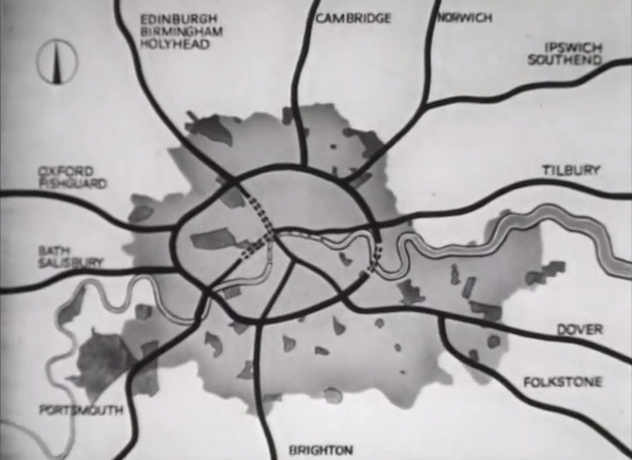

5Turning London Into One Giant Motorway

For millions of people, the idea of living next to a busy motorway is like a dream come true. If your reaction to reading that sentence was to immediately think, “no, it isn’t,” then congratulations: You’re smarter than London’s city council. In the 1960s, a plan was quietly authorized that would have seen a network of wide, concrete roads bring waves of cars zipping into every corner of the British capital. Known as the London Ringways project, it was almost scary in its cavalier attitude to preservation. Consisting of four concentric loops heading deep into the city’s heart, it would have put London into a kind of concrete chokehold. Gone would be the outer parks and green spaces, replaced with something from J.G. Ballard’s nightmares. Worst of all was Ringway One. The central loop in this spiral of madness, it would have smashed through some of London’s greatest districts, suffocating them under concrete and motorway noise. Camden Town, Hackney, Hampstead, and Islington would all have been plowed under, along with Brixton and Clapham Junction. In 1973, the Conservative government officially gave the project the green light. Thankfully, Britain in the latter half of the 20th century apparently had no money to do anything, because the project was once again halted for being too expensive. Turns out being utterly broke isn’t always a bad thing.

4John Stuart McCaig’s Scottish Colosseum

In 1896, Scottish businessman John Stuart McCaig decided to give something to his hometown of Oban. A tiny bay community on Scotland’s west coast, Oban was a town in need of many things. The one thing it didn’t need, however, was a gigantic, life-size replica of the Colosseum in Rome. Yet that’s exactly what McCaig decided to build. Known as McCaig’s Tower, everything about the project was both impractical and crazy. McCaig designed the building himself and picked its site on a hill, looming over the little bay. But while it would have been visible to everyone in town, its purpose wasn’t exactly to promote the public good. A monstrous egotist, McCaig intended to fill the finished Colosseum with numerous statues of himself and members of his family, then keep the whole thing off-limits to members of the public. It was one of the biggest vanity projects the world had ever seen—like a Victorian Trump Tower, if Donald Trump was even more of a narcissist than he already is. When McCaig died in 1902, he left behind the equivalent of £6 million in today’s money to finish the tower. His sister begged a judge to throw his will out, and the judge complied. Today, the unfinished shell is considered a local landmark.

3Demolishing Grand Central Station

We recently told you about the architectural crime that was the demolition of NYC’s Penn Station. Little did we realize that that was almost a footnote in an even more barbaric act. Between 1954 and the mid-1970s, New York Central Railroad did everything in its power to have the Grand Central Terminal pulled to the ground. If you’ve ever even set foot in there, you’ll know what a terrible idea this was. Grand Central is like something from a magical past, when catching trains was something you put a suit on to do. Yet the extent to which the station’s owners attacked it over the decades bordered on the pathological. In 1963, New York Central tried to destroy the terminal’s upper levels by building a bowling alley over them. Just weeks after it was declared a historic landmark in 1967, its new owner Stuart Saunders—the same guy who tore down the beautiful Penn Station—opened bids to raze the terminal and build a big, boxy tower in its place. When the Landmarks Commission protested, Saunders sued it. By the early 1970s, a judge had even ruled that Grand Central should be demolished, potentially invalidating the entire concept of protecting historic landmarks. It was only because Jackie Onassis wrote a very public, very eloquent letter to the mayor pleading the city to reconsider that the ruling was voted down in an appellate court by a 3-2 vote. The same lunatics who wanted to tear the place down then went on to nearly bankrupt NYC when their company suddenly went bust, requiring what was at that point the biggest bailout in history.

2Tearing Down Central London

If there’s one thing we can conclude from this article, it’s that London’s council hates everything about the city. Before the government was planning to drive motorways through the middle of the city, it was seriously considering multiple proposals to knock down just about every historic building in the center. One of the main targets was Piccadilly Circus. One of the most famous destinations in the British capital, Piccadilly Circus is a glorious ensemble of grand 19th-century architecture. Yet in the 1960s, London County Council’s Sir William Holford set out a plan calling for the demolition of three quarters of its buildings. The aim was to solve the problem of traffic congestion, which is kind of like chopping your leg off to solve the problem of an itchy foot. Tottenham Court Road was also earmarked for hideous redevelopment. Craziest of all were the plans for London’s notorious Soho district. A maze of winding streets, historic pubs, and seedy red-light clubs, Soho is today a world-class attraction. Yet in 1954, a plan was put forward to demolish the entire district and concrete the remains. In its place would be built a series of forbidding office towers and a network of sunken motorways.

1Driving A Railway Through The Middle Of Stonehenge

Stonehenge is one of the greatest monuments on Earth. A collection of ancient stones raised thousands of years ago in a corner of England, it’s as mysterious and awe-inspiring as the Pyramids or Machu Picchu. It’s also an area of great scientific value, with the entire Stonehenge site covering many kilometers and including the equally mysterious nearby stone circle of Avebury. In the 19th century, the Victorians went seemingly out of their way to destroy the whole lot. The worst attempt came in 1886, when the London South West Railway company tried to drive a railway right through the middle of the site. Aside from coming right near to Stonehenge itself, the line would have cut across the Stonehenge Cursus, a kind of ancient ditch that scientists believe predates the henge. The motion was defeated, but 10 years later, another railway line was proposed that brushed right up against the standing stones. Even this has nothing on Avebury. A vast henge that’s in some ways even grander than its more popular sibling, Avebury was sold off for housing in 1872 and nearly demolished. It’s only because a British MP named John Lubbock hastily brought up all the building sites in a desperate bid to save it that Avebury still exists today. Had the Victorians gotten their way, this famed corner of England would currently be a much culturally poorer place.