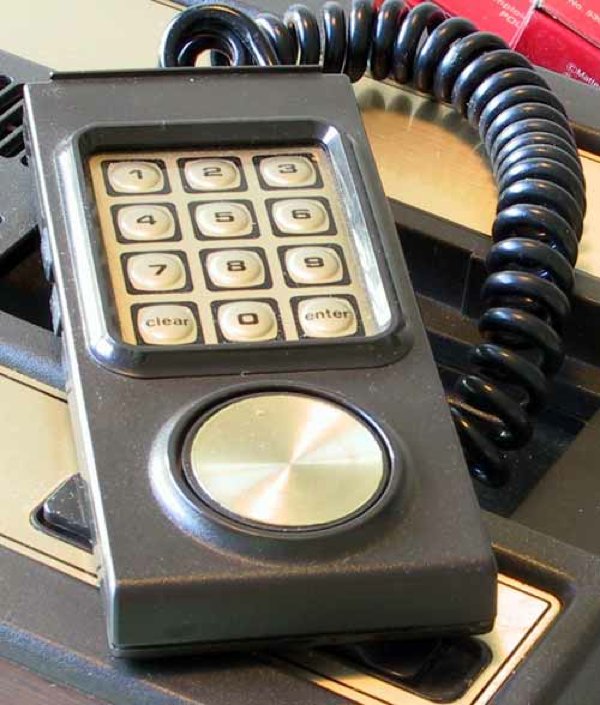

The Mattel Intellivision was a home game console released in 1979. Development began less than a year after the introduction of its main competitor / arch-nemesis, the Atari 2600. It had graphics and sound capabilities that put the 2600 to shame, but that was only the beginning of its innovations. Intellivision was the first 16-bit gaming system, the first to feature voice synthesis, and easily the first to feature downloadable games via cable. But poor marketing, along with a poorly designed non-ergonomic 16-direction control pad lead to Mattel selling only 3 million units over its lifetime. Not bad, you say? The underpowered Atari machine sold ten times that number. In 1983, the video game market crashed – only to be revived by the Nintendo NES, a system with all of the Mattel’s innovations but none of its shortcomings.

The first digital home video format was introduced in 1978, known as Laserdisc or “DiscoVision” because this was the ’70s. Brought to market just two years after the introduction of videocassettes, this high-capacity digital storage format meant video and audio quality far exceeding any VCR. Compact Discs, still four years down the road, were based on this technology. Laserdiscs boasted extremely sharp images – the likes of which had not yet been seen on home video – as well as digital surround sound. Unfortunately, the discs were heavy and easily damaged, and the players quite loud compared to VCRs. There was no recording capability, and the discs and their players were super expensive. VCRs reigned supreme until the advent of the DVD, which was a kind of mini Laserdisc.

The very first widescreen projection format, Cinerama, made IMAX look like a wussy. Projecting a Cinerama film meant projecting three synchronized 35mm projectors simultaneously onto a gigantic curved screen. While technically challenging to present and requiring a skilled projectionist (or three), the results were visually astounding and far ahead of any other method of the time. Did we say “technically challenging”? We meant “damn near impossible.” Projecting three films with perfect synchronization is every bit as hard as it sounds, and there was no means of automation. The projectionists just had to be that good. Plus, very few theaters were willing to make the necessary and expensive modifications. As a result, only a couple of dozen films ever used the format.

As the other home videocassette format, Beta is synonymous with “also-ran.” Sony’s format offered much smaller, more durable cassettes and better resolution than JVC’s competing VHS format. Betamax even beat VHS to the US and Japan markets by over a year. So what went wrong? The “format wars” between Beta and VHS (see: Sony and everyone else) are the stuff of tech legend. Sony misjudged the home video market in a number of ways, but the most likely cause of Beta’s failure was Sony’s reluctance to license its technology. JVC had no such qualms, resulting in a wide array of manufacturers selling VHS machines much more cheaply than Betamax. Also, Beta machines could initially only record for 60 minutes, compared to the 3 hours of VHS. VHS wins…

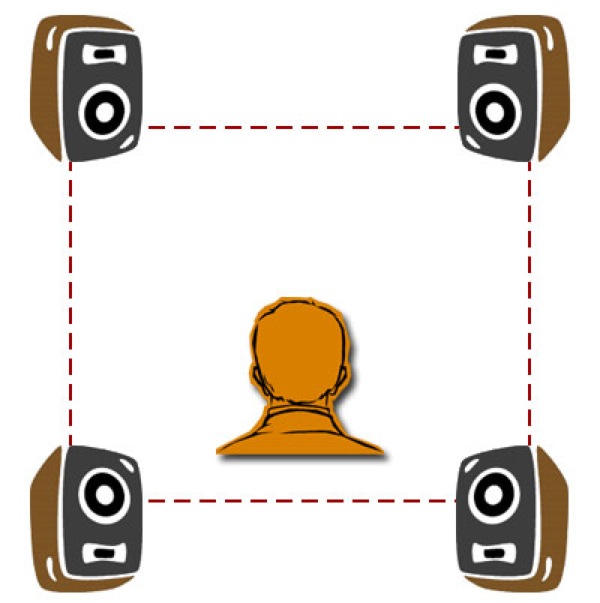

Simply put, Quad would now be called 4.0 surround sound. Like stereo, but… twice as much. It was intended to replicate the experience of live sound on speakers, which it did. Debuting in 1971, several quad vinyl records were released in differing (and incompatible) formats. Played on the right system, the “3-D audio” result was pretty spectacular. But there are about a billion ways to produce quadraphonic sound, and no single format was ever agreed upon. Dolby surround sound, which does pretty much the same thing, was standardized and eclipsed quad quite quickly. Of course, surround is primarily used for movies. For listening to music, most people think stereo is just fine.

Look familiar? That is a QR code, short for “Quick Response”, and they’ve been popping up all over the place for the last ten years or so. Storefronts, packaging… you probably have one tattooed on your butt. They’re like barcodes on crack; they serve the same purpose (as barcodes), but hold a lot more information. They were originally used to track parts during manufacture by the auto industry, but what fun is that when they can be used in advertising? The problem is, nobody knows what the hell to do with them. PR for the QR was severely lacking. A recent study showed that about 80% of college students, that most tech-savvy of demographics, have no idea what to do with a QR code. Hint: scan them with some third party app on your smart phone. And once we do figure it out, what’s our reward? Why, intrusive, in-your-face advertising, of course… what tech-savvy consumers love most of all. I have no idea what went wrong.

DATs were introduced in 1987. They were tiny little cassettes that record digitally at CD quality or better, meant to replace standard cassette tapes. They were far superior to cassettes, more durable and portable than even CDs, capable of 16-bit sampling and widely varying recording lengths. Why, they’re the Superformat of the future! And since the music industry is never scared of new technology, we can’t figure out why – oh, wait. The failure of DAT as a format for selling music was (of course) mainly due to piracy concerns. Music industry types were concerned that piracy would skyrocket with a high fidelity, recordable medium – and effectively buried the technology for consumer use. This paved the way for all-digital formats like mp3, which of course are much easier to pirate. Great job, music industry!

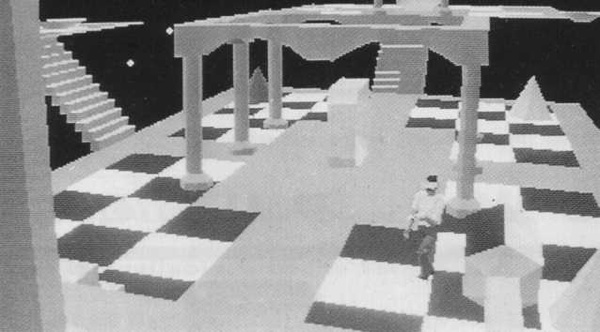

As seen in every ’90s sci-fi movie, fully immersive 3-D computer generated imagery is essentially virtual reality. Even in the early ’90s, companies like the cleverly-named Virtuality were releasing VR arcade games like “Dactyl Nightmare” that placed you right inside the cheesy, blocky action. The technology simply wasn’t advanced enough to meet the vision, and attempts at true VR were underwhelming to say the least. While technology has obviously come a long way, we’re still pretty damn far off from having a real-life Holodeck which – let’s face it – is what we all really want.

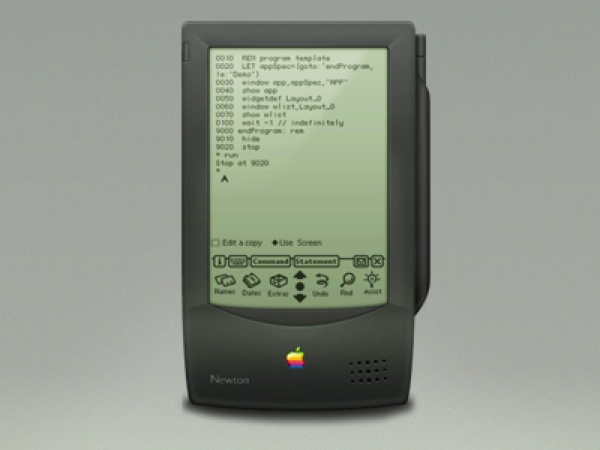

Long before Apple released the iPod and began dominating mobile devices up one side and down the other, there was this 1993 ill-advised attempt at that market. The Apple Newton was essentially the father of all PDAs, and was innovative in many ways, but was ultimately a spectacular failure. The Apple Newton PDA never quite caught on due to a hugely inaccurate handwriting recognition system and an exorbitant price tag, not to mention that it looks like a Commodore 64 mated with a tape recorder. The 1995 debut of the smaller, cheaper and more functional Palm Pilot was the final nail in its coffin. The Newton was discontinued in 1998.

In its first incarnation, DIVX will likely go down as one of the biggest tech flops of all. Its innovation was in catering to those who wanted a way to “rent” movies digitally (you know, like everyone does now), but the way it was implemented was a misstep, in the same way that falling down the stairs is a misstep. Piloted by electronics retailer Circuit City, the idea was simple enough. You rent a disc, watch it for two days then throw it away. Simple, right? Except that it was like a DVD without all the features, required a separate player that consumers had to buy, and the video rental industry fought against it tooth and nail. By the time Netflix and Blockbuster came along to make digital rentals simple, DIVX was but a memory, having been sold only between 1998 and 1999. Its legacy lives on in annoying, unnecessary software constantly trying to get you to download it for some reason. Mike Floorwalker’s blog is freakin’ sweet.