10 Ancient China

In ancient China, infant death was so common that people were not allowed to have any Yili (“mourning period”) for the death of a baby younger than three months old. In fact, parents were only allowed to cry one day for every month that the baby lived. If a baby was three months old at death, the parents only had three days to get over it and move on. Any more than that was considered to be overly dramatic. Similar to the apprehension that many women feel in the first few months of pregnancy, women were told to prepare for the possibility that their newborn babies could die. In their culture, women were trained not to see the babies as fully human yet. Until a child’s seventh birthday, it was expected that a child could succumb to disease. Citizens were instructed not to wear the white robes, which were official mourning garments, or spend the money to hold large funerals for young children. It was believed that children younger than eight years old did not fully comprehend a deeper connection to the world around them. Therefore, a child’s death was not as much of a tragedy as an adult’s death. There were many parents, however, who loved their children enough to ignore these rules. In particular, one family bought a gravestone and engraved a poem on it about the death of their five-year-old. They wrote that they would miss the child forever and that they hoped the child’s spirit would live forever with their ancestors.

9 Southern United States In The 1800s

In the early 1800s (before the age of modern photography), families who could afford the luxury would get a portrait painted. When a child died, parents in the American South desperately wanted to have an image of their son or daughter so that they would never forget the child’s face. When a child passed away, the body was called “the sitter.” After the child was laid out, the artist took measurements of the body and made a quick sketch of the child’s likeness. Then the artist worked with the parents to depict the child’s likeness as accurately as possible. Artists often painted the child surrounded by their favorite toys, games, family dogs, and other things they had loved. The artists often left clues—like dead trees in the background—to let the viewer know that this was a portrait of a dead person. In 2016, the American Folk Art Museum in New York City held an exhibition of posthumous child art. In some cases, parents would lose all their children in the span of a week if the children all caught the same deadly disease. In those cases, one portrait would depict all the children together.

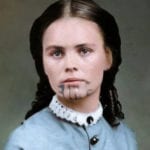

8 Victorian England

By the mid-1800s, it was cheaper to get a photograph taken than to commission a painted portrait. Similar to the death portraits in the American South, families in Victorian England wanted to make sure that they captured an image of their child before the funeral. In some cases, the child’s dead body was propped up while their living brothers and sisters stood together for a truly horrifying sibling photograph. In other cases, parents would hold their babies one last time while the photo was taken. However, this was not a tradition just for dead children. Plenty of deceased adults were also photographed. But it was more common for children to be photographed together with loved ones or, at the very least, their collection of toys or flowers. Adults were almost always photographed alone. In one photo, the entire extended family—including the cat—surrounded a dead baby, who was laid out on the floor.

7 Ancient Egypt

In ancient Egypt, 30 percent of children died in their first year. It was basically a miracle if any child actually grew up to be an adult. In fact, it was so common for babies to die that they were not buried in a graveyard with adults. Families were expected to create graves in their own yards. Mothers were understandably very protective of any child who had actually survived. They would give their children “magic” amulets and dolls that were meant to protect the children from death. In fact, the graves of children were filled with dolls and toys (such as the one pictured above). Some historians believe that many of these toys could have also been magic amulets to protect the children’s spirits in the afterlife. As the child mortality rate was so high, many ancient Egyptians did not even name their children until they were toddlers. For this reason, it is easy to identify a child’s grave because many of them simply say “The Osiris” (“The Dead One”).

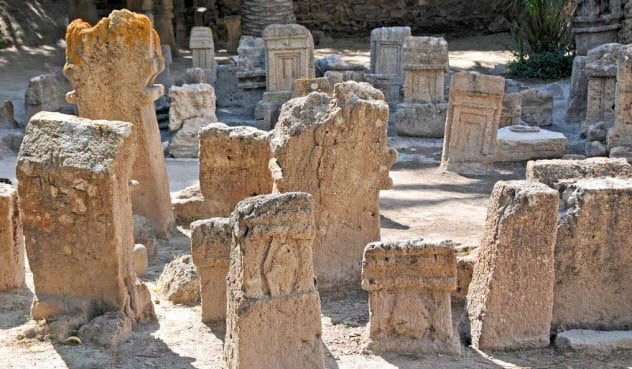

6 Ancient Carthage

On the site of the ancient city of Carthage in modern-day Tunisia, there lies a graveyard that is filled entirely with the cremated bodies of babies and fetuses. For years, it was believed that this burial site was for children who were killed as child sacrifices. One of the biggest arguments for this belief was that the bodies of goats were also buried in the same area. The Bible mentions Carthage as one of the evil pagan groups that worshiped the god Baal, who demanded that babies be thrown on a fire. In 2012, researchers explained that much of what was written in the Bible must have been anti-Carthage propaganda to help convince people to join Judaism and later Christianity. It is not difficult to imagine that this may be true considering the brutal conflict between Jews and Arabs in Israel and Palestine—even today. Researchers studied the teeth of these children’s remains and concluded that many of them must not have been sacrifices if they were fetuses and stillborn. The god Baal wanted sacrifices from healthy living beings. Researchers from Hebrew University in Jerusalem claimed that the heat of the cremation must have damaged the dental evidence of young babies. So it does not discount what they have always believed about Carthage. Oxford University researchers also chimed in, bringing up evidence to prove that Carthaginians were, in fact, sacrificing children. The most obvious pieces of evidence are stone slab grave markers engraved with messages from parents who willingly gave up their babies. These parents hoped that the god Baal would shine good fortune on them in exchange for their children’s lives.

5 Japan’s Mizuko Kuyo Memorials

In Japan, the guilt and pain associated with abortion, stillbirth, and miscarriage became something that was talked about more openly among women. In response to their mourning, they began a tradition called mizuko kuyo, which is a funeral service specifically for unborn babies. Tiny statues of Jizo, a Buddhist figure believed to protect women and children, are lined up at temples. Women who are mourning and cannot necessarily hold proper funerals may visit a Buddhist temple and decorate their own tiny Jizo statues with knitted bonnets, sweaters, and toys in honor of their unborn children. The women also say a prayer for their child’s spirit. This practice is thought to be so comforting to mothers of miscarried children that it has been adopted by women in the United States as well. In 1978, a Buddhist temple with a mizuko kuyo section appeared in Hawaii. Even in the mainland United States, women have found comfort in buying Jizo statues for their gardens.

4 Ancient ChamorrosMariana Islands

Chamorros were the native people of the Mariana Islands. When anyone passed away, their body was laid out in the home and the head was propped up on a basket. The Chamorros believed that the soul left the head and entered the empty basket. They invited the spirit to stay as long as it wanted—unless the death was violent or involved extreme suffering. In those cases, the Chamorros took this as a bad omen that the ancestors had judged the deceased as not worthy of a peaceful death. The Chamorros assumed that the person was going to Hell, so they did not invite the spirit to hang out. Taking pieces of the deceased person’s body and drying them out so that they could be kept in the family home was considered a way to honor the dead person. In some cases, hands and skulls were removed after the body had decomposed and were kept as a token of that loved one’s life. With dead children, mothers usually took a lock of their child’s hair even if they didn’t keep any actual body parts. A grieving mother would also create a necklace out of a cord. She would add a knot to the necklace every day to track how many days she had been mourning the death of her child.

3 Ancient Greece And Rome

The famous philosopher Aristotle wrote a good number of things about childbirth, including his opinion that any child born with a disability should die. Rather than murder a baby, the parents were instructed to leave the child exposed to the elements. Aristotle was also proabortion. He said that if a family could not afford to have more children, it was less cruel to kill the baby in its developmental stages rather than killing a perfectly healthy child after it was born. In ancient Rome, the idea of leaving children to die of exposure was quite common. Their great legend of Romulus and Remus is about two brothers who were left to die by their mother and then were raised by wolves. For a long time, historians speculated that male children were favored over females. But recent DNA analysis has revealed that this is not true and that parents must have had a variety of reasons for leaving babies to die. At that time, newborns were not considered to be human yet, so parents who discarded them so easily clearly did not mourn them.

2 Navajo Native Americans

The Navajo people continue the long-held tradition of dressing the body of a deceased person in their finest clothing, jewelry, and feathers before burial. No one is allowed to speak the name of the dead person in the first few days following the death for fear that their spirit could be pulled back to the living realm. Once the body has been officially buried, anyone present at the funeral must change their clothing and wash themselves because they believe that the chindi ghost hangs around during a funeral. The chindi is all the negative things about a person’s soul because only the good things can make it to the afterlife. Children have less chindi as they are generally innocent and have not committed many evil acts during their lives. Chindi is taken so seriously that Navajo tribes will burn down a teepee or “hogan” if anyone dies inside. The Navajo do not want to risk being infected by the evil ghost. Even with children and babies, anything touched by the child at the time of death was discarded as well. If a baby died in a cradle inside the hogan, it wasn’t necessary to burn the house down. But the entire cradle was buried with the body for fear that the chindi ghost might be lingering on the object.

1 Uganda’s Child Sacrifices

In 2011, reporters from the BBC pretended to be businessmen and went undercover in Uganda. They asked a witch doctor if they could have a spell for good luck for their fictional new real estate business. The witch doctor killed a goat in their honor and explained that they needed to kill a child if they were really serious about trying to get good luck. The witch doctor explained that the “businessmen” could bury the child’s remains beneath their construction site when the ritual was over. If they didn’t want the body underneath their business, they could cut off the child’s head, genitals, hands, and feet and scatter the body parts to make the child more difficult to identify. The basic good luck spell—the one with the goat slaughter—cost $400. If the “businessmen” wanted to pay for a stronger child sacrifice spell, it would cost much more. While this is not condoned by the government, local police officers do nothing to stop these witch doctors because the officers are bribed to ignore these child sacrifices. In one case, a woman who was hysterical over the death of her grandson was offered money to keep quiet. Depending on the demand for spells, there are 20 to 30 sacrifices per year. However, the BBC believes that the true number is in the hundreds because many deaths go undocumented with orphans. Parents in Uganda have to keep a close eye on their children. Any parent who is in mourning or pursues justice against their child’s killer is given enough money to convince them to keep quiet about it. In a country where people live in extreme poverty, it seems that money is enough to get away with literally anything. Shannon Quinn is a writer and entrepreneur from the Philadelphia area. You can also find her on Twitter.

![]()