Now, in my admittedly biased and prejudiced mind, not all Last Stands are created equal. So, for the purpose of this list, I’ve got five criteria in mind. Not every last stand here meets all five, but they must meet at least three.

- If you are the aggressor, you can’t have a Last Stand because you are getting your just desserts. Simply put, you started it and if you hadn’t started it, you wouldn’t be getting wiped out to the last man, now would you? (Think Custer) 2. The odds are laughably against your team. We’re talking AT LEAST 3:1 against and the worse the odds, the burlier the last stand glory. 3. Everybody, or at least just about everybody, dies. It’s not a Last Stand if enough of you are left to make another last stand at some point. 4. Everyone EXPECTS to die. No surrender even if asked to. As one burly sergeant in a furball of a fight put it, “Surrender? Not bloody likely!” (Exception: You surrender on YOUR terms and it’s honored.) 5. The sacrifice has to mean something in the larger scheme of things. Otherwise, you should have bloody well retreated or something to try staying alive since what you did was get everyone killed for nothing. So, with no further ado, and in no particular order, here are my suggestions for the burliest of the burly Last Stands.

This was the stuff legends are made of and since Frank Miller’s film 300 came out, a whole new generation of people have been acquainted with the heroic sacrifice of Leonidas and his handpicked guard of 300 warriors, all of whom had mature sons who could carry on the family name. What a lot of people don’t seem to remember is that as awesome as Leo and his wild bunch were, they didn’t stand completely alone. Other city-states, notably Arcadia and Thespia, sent troops as well, so the force opposing the massive Persian army was closer to 6,000 than just 300. Still, that this group stopped those thousands cold in their tracks at the Hot Gates for three days and in the end were only dislodged by treachery is nothing short of amazing. The action scored a perfect 5 out of 5 on the criteria. The best legend, probably apocryphal – but maybe not, was one Spartan hoplite’s reply to a Persian envoy’s boast that, “Our arrows will blot out the Sun.” The hoplite replied, “So much the better, for then we shall fight in the shade!”

Rome was sacked by the troops of the Holy Roman Empire under Emperor Charles V in 1527. When the troops, mostly rabble and mercenaries, of the empire breached the city, they immediately ignored the orders of Charles and pretty much everyone else in command and made straight for Vatican Hill intent on pillaging the richest treasures in Christendom. They also had murder on their mind and Pope Clement VII was high on the list of targets. The famous Swiss Guards, who used to do more than just stand around looking pretty for tourists, formed a fighting square on the steps of St. Peter’s Basilica to face upwards of 20,000 bloodthirsty troops who were storming the city. Only 189 Guardsmen remained after the fighting to take the city, but these troops chose to make their stand in hopes of buying Clement time to escape the city through one of the warrens of tunnels under Rome. Clement made good his escape as the Guard managed to hold the porch of the church and prevent the doors from falling, but only 42 Swiss Guards survived and none of them were uninjured. Again, this one scores a 5 out of 5 and proves that when the Swiss decide not to be neutral, they aren’t a bunch to take lightly.

This one siege and especially its climactic pre-dawn final battle is the reason natives of Texas poke their chests out a little farther than most other Americans. It is a singular event in Texan history and it’s what lead directly to Texas becoming first a nation and later a state in the United States of America. Not only that, but “Remember the Alamo!” has rung down the years as a major battlecry for people who’ve never crossed the Texan border, but who feel a giddy sense of bravado in the face of utter annihilation. At the old Spanish mission, 182 poorly armed Texas rebels faced upwards of 2000 crack Mexican troops under the command of the finest Mexican general, Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna. The Mexicans had cavalry and a battery of cannon. The Texans had grit, determination, and cannons with very little ammunition. For 12 days, the Texans stood down Santa Anna, enduring bombardments daily. Finally, Santa Anna had enough and ordered a full assault on the mission in a surprise pre-dawn attack. Every defender of the mission was killed but Santa Anna did spare the women and children as well as sparing and freeing two African American slaves found in the fort. This last stand garners a 4.5 out of 5 because technically, the Mexicans were the “good guys” since the Texans were rebels against the lawful authority in Mexico City.

This small engagement in Mexico while much of the world was focused on the American Civil War to the north, put the French Foreign Legion on the map and began a legend that persists today in the unofficial motto, “The Legion dies, it does not surrender.” Everything fell out because a group of 65 Foreign Legion troops, led by Capt. Jean Danjou were carrying supplies to Veracruz in support of the French campaign in Mexico under Napoleon III. Caught out in the open, the French troops managed to make a fighting retreat to the small hacienda of Cameron. There, surrounded and backs to the wall, the handful of Legionnaires fought like they were possessed. They repulsed attack after attack, cavalry charge after cavalry charge, until their ammunition began to run low. Even after Capt. Danjou was felled by a bullet to the chest, his men fought on. Finally, only six of the men remained and they were out of bullets and powder. At this point, they have killed enough Mexicans to surrender honorably. After all, only six are left ALIVE, much less standing. But no, led by the highest remaining NCO, a corporal, the six men fixed bayonets and, with the cry of “Vive l’France”, charged the Mexican forces. Three were struck by rifle fire and killed outright. The remaining three were surrounded, wrestled to the ground and asked to surrender. Most men would have said fine and thanked their luck they were alive. Not this bunch. One of the men looked up and said they would surrender only if they were allowed to keep their regimental Colors, keep their weapons, carry their dead with them, AND be given a safe conduct escort to their own lines. According to the accounts of eyewitnesses, the Mexican commander shook his head, laughed and ordered his men to comply with the Legionnaires’ demands. “After all,” he is supposed to have said, “What is one to do with devils like these?” To this day, April 30 is called Cameron Day in France and is celebrated by the Legion much as the Marine Corps Birthday is celebrated every November in America.

This battle would again only garner a 4 out of 5 on the criteria because Saigo’s samurai were technically rebels. BUT, they were rebels because the Emperor was destroying their way of life. Bushido and the sword had ruled samurai behavior for over a thousand years and now the nobility of the samurai and his training were being swept aside in favor of conscript troops with rapid firing weapons. So, the samurai under their commander Saigo were retreating to their base of operations when they were caught and surrounded on the hill of Shiroyama. The 300 of them had their traditional bows and, of course, their matchless katanas. The 30,000 Imperial troops had rifled muskets and gatling guns. The Imperial commander asked Saigo to surrender peacefully and be spared, but, being a samurai, Saigo couldn’t really do that. Instead, he spent the night of September 23 getting buzzed on sake and ready to die. At 3:00 AM, the Imperial troops began an artillery bombardment followed by a full frontal attack. Saigo was twice wounded before committing ritual suicide to avoid the dishonor of capture. The thirty men who survived the artillery barrage charged the Imperial lines and began laying about them with their katanas. They acquitted themselves well, but in the end, every one of them was killed and the way of the samurai was dead . . . at least until the start of World War II.

Okay, this is another slightly technical violation of my criteria. After all, if the Brits hadn’t been trying to take the Zulu’s land, Rorke’s Drift never would have happened. BUT, in my defense, these particular 139 soldiers weren’t invading anything. They were left behind while the “big boys” went off to get massacred at the Battle of Islawandha. No, this was a group of cooks, supply clerks, Royal Engineers, and other guys who could fight if they had to, but hadn’t really been called upon very much. They were the prime example of the “in the rear with the gear” soldiers. Unfortunately, all their buddies were wiped out at the aforementioned Battle of Islawandha. To make matters worse, a whole crap load of Zulus didn’t get to take part in the battle because everyone was dead before they got there. So, those bored Zulus decided to take out their frustrations on the supply depot at Rorke’s Drift. The Zulus had numbers, surprise, the high ground, and knowledge of the terrain. The defenders had bags of grain, Martini-Henry rifles, and bayonets “with some guts behind them”. The Zulus attacked in massive waves all through the afternoon of January 22 and through the night and early morning of January 23. They were gathering for another assault when their scouts spotted the British relief column complete with cannon and decided to retire. The defenders gained a new respect for the Zulus and in the process garnered 11 Victoria Crosses, the most ever awarded for a single engagement. True, they weren’t wiped out, but when they looked up and saw every surrounding hill bristling with Zulu warriors, no one thought he was getting out alive.

1,400 Malay, British, Indian and Australian soldiers faced off against 13,000 Japanese troops in an attempt to save Singapore or at least give the civilians time to evacuate. Soldiers from the Royal Malay Regiment, The Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire Regiment, the British 2nd Loyals Regiment, the 44th Indian Brigade and the 22nd Australian Brigade made a futile attempt to stop the advancing Japanese towards the centre of Singapore. The majority of the defenders fell in the battle. Those that did not became prisoners who would later be pressed into service on the Thai-Burma Railroad where they would be forced to built a famous bridge over a famous river. In the final hours of battle, a Malay soldier, 2nd Lieutenant Adnan Bin Saidi, led a 42-man platoon against thousands of invaders, leaving himself as a sole survivor. The Japanese suffered a disproportionately high number of casualties because of these men’s bravery so as punishment for being burly and courageous they tortured Adnan before executing him.

Early in the Battle of the Bulge about 12,000 under-equipped and exhausted US Paratroopers of the 101st Airborne Division seized the town of Bastogne to defend this strategic crossroads from the German Advance. They were promptly and completely surrounded by roughly 15 Divisions of Germans. The 101st could only be sustained by airdrops from C-47s and things looked suitably grim. Seeing the hopelessness of the American position, German commander, General Heinrich Freiherr von Lüttwitz asked the 101st’s acting commander, Captain Anthony McAuliffe to surrender, McAuliffe’s famously terse reply was “Nuts!”. Under their impetuous commander, the unit held off multiple German Panzer attacks, until eventually relieved by George S. Patton’s US Third Army on December 26. One of the units of the 101st to take part in the battle was the legendary Easy Company immortalized in the TV series “Band of Brothers.”

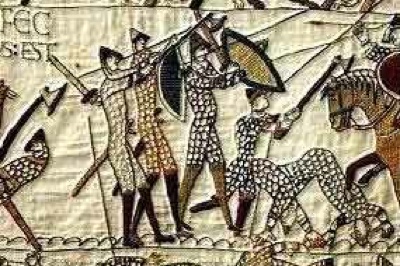

On January 6, 1066, Harold Godwinson became King Harold II following the death of his brother-in-law, Edward the Confessor. By late summer, he was faced with two imminent attempts to invade England. The first came in the northeast from his traitorous brother, Tostig, and King Harald Hardraada of Norway. While celebrating his defeat of Hardraada at a victory feast, Harold received word that Duke William the Bastard had landed at Pevensey in the south with 7,000 men. Harold gathered his forces, marched south to London, and by the evening of October 13, deployed his forces along Battle, or Senlac, Ridge near Hastings. The battle developed into a deadly engagement between the Saxon infantry and the Norman cavalry and archers. Initially, Norman arrows were harmlessly deflected by Saxon shields, and Saxon axes and spears shattered the first Norman charge. Overcome by confidence, the Saxon infantry unwisely followed the retreating cavalry in reckless pursuit and were cut down by the Norman reserve. Harold reformed his forces and the Saxons braced for additional charges. The battle evolved into relentless pounding on the Saxon line by the Norman cavalry. The Saxons more than held their own and inflicted heavy casualties. Just before evening, William feigned a general withdrawal and many Saxons again broke ranks to pursue. The knights wheeled round and destroyed the Saxon infantry in the open field. Harold and his housecarl bodyguard remained intact and just as formidable on the ridge. William ordered a final charge. This time he first had his archers aim not at the Saxon shields but release their volleys into the air so the arrows would fall on the Saxons from above. The tactic worked, but the Harold and his housecarls fought on until an arrow struck the king in the eye. As Harold struggled to pull it free, four Norman knights (one of whom may have been William) attacked. One speared Harold in the chest, and a second nearly decapitated him with a sword. As he fell, the other two Normans delivered additional blows. With Harold’s fall, the Saxon forces panicked and retreated into the nearby woods except for the housecarls who fought to the death around the body of their dead king.

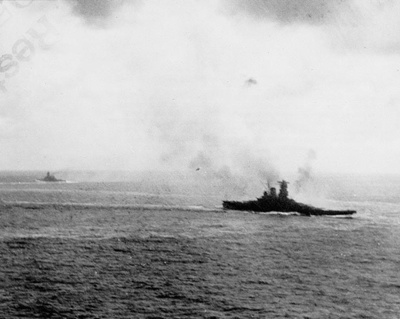

The Battle Off Samar (also known as “The Last Stand of the Tin Can Sailors) has been cited by historians as one of the greatest military mismatches in naval history. It took place in the Philippine Sea off Samar Island, in the Philippines. It all started when Admiral William Halsey, Jr. was lured into taking his powerful U.S. Third Fleet after a Japanese decoy fleet. He thought this fleet was the main Japanese battle group and if he could catch them, he could destroy what was left of the Japanese navy. To defend his rear, he left behind only “Taffy 3,” a light screen of destroyers, destroyer escorts, and three escort “baby” carriers. A powerful Japanese surface force of battleships and cruisers thought to have been defeated and in retreat earlier had instead turned around unobserved and came upon the tiny force of tiny ships. With nothing else he could do, Admiral Spruance in command of Taffy 3 gave the order, “Small Boys (meaning destroyers and escorts) attack.” With that order Taffy 3’s destroyers and destroyer escort desperately charged forward and attacked with 5 inch guns which could not penetrate even the thinnest armor of the Japanese armada and torpedoes, while carrier aircraft dropped bombs and depth charges, then out of bombs, strafed the bridges of the Japanese heavy ships. While the Americans suffered more losses in ships and men than were lost at the Battle of Midway, they caused so much damage and confusion to convince the Japanese commander, Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita thought he had stumbled upon the lead element of Halsey’s main fleet. Fearing for his forces, he ordered his ships to regroup and ultimately withdraw rather than advancing to sink troop and supply ships at Leyte Gulf. Taffy 3’s bold defense in the face of overwhelmingly superior firepower saved the invasion of the Phillippines.