SEE ALSO: 10 Facts About Santa Muerte, Our Lady Of Holy Death The 3-day event kicks off with All Hallows’ Eve on October 31. This is then followed by All Saints’ Day (November 1) and All Souls’ Day (November 2), when the spirits of deceased children and adults are said to return. While this may not sound particularly uplifting, Mexicans have a rather complicated take on death. The Day of the Dead is a time to celebrate loved ones who have passed. Altars are erected to show the dead how much they are missed. Families congregate in candlelit cemeteries and tell stories. And spectacular festivals bring Mexican cities to life. School kids even write poetic obituaries called calaveritas. These playful rhymes are traditionally used to mock the living, including Mexican politicians and celebrities, by narrating how they will die. The Day of the Dead is a spiritually and culturally unique event. From butterflies to skeletons, every aspect of this spectacular holiday has some hidden meaning. So let us take a look at just some of the most surprising Day of the Dead facts and traditions.

10 The Underworld Ruler Who Inspired an Icon

One of the most iconic figures of Dia de Muertos is a female skeleton called La Calavera Catrina (a.k.a. “Elegant Skull”). The locals make statues of La Catrina and place them on altars. Her characteristic face is often painted across storefronts. And party-goers mimic her appearance with sugar skull makeup. She symbolizes the idea that death is the great equalizer. It comes for us all, regardless of wealth. The Mexican artist Jose Guadalupe Posada originally created La Catrina. While managing his own lithography business in Mexico City, Posada created prints that challenged government corruption and social inequality. He took aim at President Porfirio Diaz, believing the seven-term ruler was hoarding wealth at the expense of Mexico’s underclass. The first drawing of La Catrina was produced in 1910, in which she is shown wearing garments of European high society. The satirical piece represented the destruction of Mexico’s wealthy elite, while also mocking President Diaz’s fondness for European culture. The illustration’s original title, “La Calavera Garbancera,” mocked native Mexicans who tried to make themselves look European. But La Catrina has even deeper roots. Posada’s inspiration came from the queen of the Aztec underworld, Mictecacihuatl (a.k.a. the Lady of the Land of the Dead). It was said that Mictecacihuatl guarded a chamber full of human bones. She not only protected the souls of the dead but even offered them safe passage between different planes. Posada’s work was closely followed by the painter Diego Rivera. In 1947, he featured La Catrina in his now-famous mural “Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in the Alameda Central.” La Catrina has been the poster child for the Day of the Dead ever since.[1]

9 Altars of the Dead

The altar of the dead (altar de muertos) is the cornerstone of any Day of the Dead celebration. Seen throughout rural and urban Mexico, these shrines are used to present gifts to the spirits of the dead. The spirits find the offerings (ofrendas) by following trails of flowers and burning candles. The pungent smell of copal incense purifies the souls of approaching spirits and wards of evil. Each altar is also crammed with the favorite food and drink of a family’s dead relative. Sugar skulls, the bread of the dead (pan de muertos), tamales, tequila, and beer are offered to nourish the soul. Other common items include statues, photos, prized possessions, and poems. While offerings are usually made at home, many families prefer to place altars at the gravestones of their loved ones. Cemeteries are an important venue for the Day of the Dead celebrations. Gravesite bands play music. Hundreds of candles cast a warm glow along the rows of headstones. And the locals spend the night telling stories about their loved ones. The ofrendas seen in public squares are usually dedicated to famous Mexican figures. The Mexico City Metropolitan Cathedral has installed an altar dedicated to the late Pope John Paul II. And artists compete to build the best altars in Constitution Square. The altar is a fusion of Aztec and Catholic traditions. It is divided into levels that represent the various planes of existence. Some altars have two levels (heaven and earth) or three levels (heaven, earth, and the underworld). Seven-tier altars are the most common. They represent the seven levels a soul must traverse in order to reach either the underworld or heaven.[2]

8 Bone Washing

In the remote town of Pomuch, situated in southeastern Mexico, locals celebrate the Day of the Dead by cleaning the bones of their deceased relatives. The Maya locals are buried in accordance with normal tradition. After three years, the “purified” remains are exhumed. The dirt-covered bones are then cleaned using brushes and placed in special wooden boxes, ready for display. In the run up to the Day of the Dead, the townspeople visit the local cemetery and begin the cleaning ritual. A touch morbid to most Westerners, the tradition is actually a happy one. The tombstones are painted. Shrines are brightly decorated with flowers and candles. The colorful interiors of the wooden display boxes are repaired or replaced. And the cemetery becomes alive with stories and jokes. Some enterprising residents have even turned bone washing into a business. Cemetery worker Venancio Tus Chi offers a bone washing service for just $2. According to Venancio, the practice is important to ensure returning souls “see they haven’t been forgotten.” The Maya townsfolk believe bone washing guarantees a peaceful existence in the afterlife. It is said that the spirits of any neglected remains return to haunt the streets of Pomuch.[3]

7 The Mexican Hairless Dog

Movie buffs may recall Disney Pixar’s take on the Day of the Dead. The 2017 animated film Coco features a playful dog named Dante. The dog guides his young owner through the Land of the Dead, eventually helping him to escape. Dante belongs to the Xoloitzcuintle breed of hairless dog. The Xoloitzcuintle dog derives its name from Xolotl, the Aztec god of lightning and fire. Legend has it that the gods remade the sun many times. But on their fifth attempt, the celestial body would not move. In one version of the creation myth, Xolotl attempted to jumpstart the sun by sacrificing the other gods. He then traveled to the Land of the Dead to retrieve the bones of the humans who had died in the fourth life-death cycle. The Aztecs believed Xolotl was responsible for their very existence, using the bones of the underworld to forge the current generation of humans. He then served as the “Night Traveler,” guiding the sun safely through the underworld each night. Xolotl, depicted with the head of a dog, made the Xolos to protect humans and guide their souls to the underworld. This meant the Aztecs would often sacrifice the dogs and bury them with the dead. This practice eventually died out, as clay statues were used instead. While Disney’s Coco was well received, the company’s attempts to trademark the words “Dia de los Muertos” caused public outcry. Luckily, the company quickly reversed its decision.[4]

6 Breaking Bad and the Santa Muerte Ritual

La Calavera Catrina is the secular, and generally accepted, icon of Dia de Muertos. But La Catrina was preceded by a more sinister figure: Santa Muerte. Also known by the name “Our Lady of Holy Death,” Santa Muerte is a female folk saint who emerged soon after the Spanish Inquisition. Her appearance, similar to that of the Grim Reaper, is likely the fusion of European Catholicism and Mesoamerican mysticism. She is often depicted holding a scythe and a globe or scales. Support for Santa Muerte remains controversial and is strongly discouraged by the Catholic Church. But in recent years, her following has grown. The saint now has over 10 million followers, representing the fastest growing religion throughout North and South America. For many Mexicans, she is also an important part of Dia de Muertos. Believers dedicate shrines to their saint. They present offerings of tequila, cigarettes, food, and bones. It is hoped Santa Muerte will reciprocate by granting her worshippers’ wishes. While most Mexicans wish for peace and prosperity, others are not as kind natured. The Skeleton Saint now plays a prominent role in narco-culture. According to law enforcement agencies, drug dealers have prayed to Santa Muerte for help smuggling drugs across the U.S.-Mexico border. “Officers are entering homes on drug search warrants and they’re encountering elaborate Santa Muerte shrines,” explained Robert Almonte, a former narcotics officer. Mexican cartels, like La Familia Michoacana and the Gulf Cartel, have even made human sacrifices to Santa Muerte. In 2008, the Gulf Cartel captured members of a rival gang and executed them in front of a Santa Muerte shrine. Other offerings have included human heads, hearts, and skin. In the television show Breaking Bad, two Mexican hit men are sent to kill the teacher-cum-meth-cook Walter White. Before making their voyage, they are seen crawling on their bellies towards a ramshackle hut. Once there, they make a sacrifice and place a picture of their target at a candle-lit shrine. Their deity? Santa Muerte.[5]

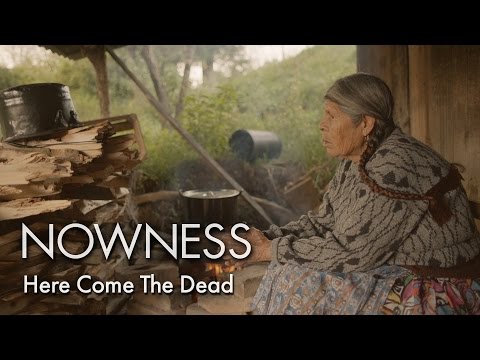

5 Guiding the Spirits

The Day of the Dead coincides with the migration of millions of monarch butterflies. Every October, the beautiful creatures journey south to Mexico. This incredible 2,000-mile trip takes several months to complete. These butterflies are much larger and stronger than your typical garden-variety monarchs and can survive up to eight months. How they cross such vast distances, scientists do not know. However, many Mexicans believe the butterfly’s migration pattern is no mere coincidence. Watch this video on YouTube The Mazahua and Purepecha tribes believe the monarchs hold the spirits of their dead relatives. One month before the Day of the Dead, the Mazahua ring a bell to call the butterflies. “Here come the dead,” cry the tribe members. They then leave bowls of water out for the thirsty travelers. This belief has even affected the design of the tribe’s coffins. A small hole is made in each casket to ensure the “butterfly souls” can escape the graves. These souls are helped in other ways, too. Marigold flower petals are strewn across graves to awaken the spirits of the dead. It is believed the Mexican marigold (Tagetes erecta) attracts the spirits with its potent scent and bright orange petals. The Mexican people sometimes use the petals to fashion pathways, guiding the spirits to elaborately decorated altars. The Aztecs believed Marigolds held a sacred connection to the sun and placed them over bodies of the dead. They performed human sacrifices to appease Huitzilopochtli, the god of sun and war, in the hopes of stopping the sun from falling down. The sun was not only the key to life but a celestial shepherd that guided the spirits to the underworld.[6]

4 The Cemetery Crisis

In Mexico City, the Day of the Dead is under threat. The city’s cemeteries are now so full that public officials are resorting to exhuming corpses, just to find space for new bodies. Once the burial rights expire, the old remains are handed over to any surviving family members for cremation. If there is no family to contact, the old remains are re-buried underneath the new ones. With the capital’s population at 9 million and counting, the government has now proposed placing tighter limits on how long bodies can remain buried. Some cemeteries have even chosen to exhume dead bodies after just 1 year. “What really bothers us is that they don’t respect our loved ones,” explained Jose Jimenez, a cemetery administrator based in one of the city’s smaller boroughs. “They come a year or two after we bury them, take them out of the grave and bury whoever is next.” Many inhabitants are worried that the city’s recent attempts to promote cremation could threaten the Day of the Dead and its unique traditions. Exhumation would prevent certain families from visiting the graves of their loved ones – an essential part of the Day of the Dead celebrations. The Catholic Church had previously imposed a ban on cremations. Church leaders eventually capitulated when it became clear that burial plots were in short supply. But more conservative Catholics have remained opposed to cremation. They either pay high sums for burial rights or use above-ground mausoleums and crypts, in which bodies are stacked on top of each other.[7]

3 Graveyard Crime and Bulletproof Mausoleums

Gravesite visits on November 1 and November 2 are a prime target for thieves. With crime spiraling out of control, many party-goers have chosen to avoid gravesites altogether. The Iztapalapa graveyard in Mexico City has experienced a substantial drop in visitors during the Day of the Dead. Around 31,000 people visited the site in 2005. In 2015, this figure was down to 12,000 visitors. The local police now patrol the graveyards to keep mourners safe. Many have chosen, instead, to celebrate the Day of the Dead at home. Rosa Maria Aloron, an Iztapalapa local, now visits the graves of her family several weeks before the holiday. “Many of my friends have been robbed here, so it’s better to come earlier,” she explained. Activists have used the Day of the Dead to spotlight Mexico’s homicide problem. Photos of the victims of violent crime, gang warfare, mass shootings, and kidnappings are often placed at special altars throughout Mexico. It is not uncommon to see vigils at the Angel of Independence statue at the heart of the nation’s capital. Even dead drug cartels are no longer safe. Culiacan, in northwestern Mexico, is home to the Sinaloa cartel. The Jardines Del Humaya cemetery was built to house the bodies of cartel members and their families. The site’s mausoleums are protected with security gates, cameras, and bulletproof glass. Costing up to $500,000, these elaborate structures contain televisions, air conditioning units, and expensive bottles of alcohol.[8]

2 James Bond Inspires Mexico City Festival

The opening sequence to James Bond’s twenty-fourth outing, Spectre, takes place during the Day of the Dead. We follow 007 through a bustling Dia de Muertos festival in Mexico City. The impressive spectacle features giant skeleton marionettes, musical bands, dancers, and marigold-covered crucifixes. Female revelers role play as La Catrina. And the men dress up as dapper skeletons. Before Spectre’s release, no such festival had ever taken place in Mexico City. So in 2016, government officials teamed up with the city’s tourist board to make the event a reality. Hundreds of thousands now attend the festival every year. A procession of marching bands and dancers make their way through the streets, along with enormous mojiganga puppets. These looming characters are made out of wooden frames and papier-mache. The puppeteer operates the mojiganga from inside, shaking their body to make the giant dance. The Skull Carnival’s army of dancing skeletons also passes through the 1-kilometer route. Aztec warriors on roller skates serve to remind Mexicans of their heritage. And spirit animal floats add a touch of flare to the occasion. These colorful sculptures, called alebrijes, were first created by the Mexican artist Pedro Linares. He saw the mythical animals in his dreams and decided to recreate them. From donkeys with butterfly wings to rooster-bull hybrids, Linares’ imaginings are a sight to behold.[9]

1 Dances with Old Men… and Fish

The Dance of the Old Men (Danza de los Viejitos) is another export from the Purepecha people. The dance, often seen during Day of the Dead festivities, is as deceptive as it is comical. The routine typically needs three or more dancers, each of whom wears the mask of an elderly man. It’s a slow start. The decrepit, toothless men appear infirm and poorly coordinated. The group hobbles about on canes, occasionally colliding with one another. But as the tempo of the music quickens, the wizened creatures become alive with rhythm. Foot stomping (zapateado) is timed to match the rhythm of the violins and guitars. And the lively affair sometimes ends with the old men collapsing with exhaustion. Watch this video on YouTube The Dance of the Old Men is a pre-colonial dance. It was used to praise Huehueteotl, the old god of fire. Huehueteotl is often himself portrayed as an old man, saddled with a brazier of burning coals. The dance was eventually modified to playfully mock the Spanish conquistadors, whom the Mesoamericans believed had become infirm from their own idleness. The Dance of the Fish (Danza del Pescado) is another remarkable display. A dancer dons a large fish costume and tries to evade a bunch of fishermen and a crocodile. Other performers sport strings of small wooden fish, which clack to the beat of the drums. At one point a mermaid even gets in on the action. Fishermen dotted across certain parts of the Balsas River perform the dance to bring hunters good fortune.[10]