10 Murphy

The most common and well-known of Irish surnames, Murphy has a long history. It is derived from the ninth-century Gaelic names MacMurchadha (which arose in Ulster) and O’Murchadha (which emerged independently several times across Ireland), both meaning “son of the sea warrior.” Irish family names were traditionally taken from the heads of tribes or prominent warriors. As Ireland, the Isle of Man, and northern England spent several centuries under the control of the seagoing Vikings, a connection is highly likely. These Gaelic names were later anglicized due to the English occupation of Ireland. Clans of Murphys were spread across ancient Ireland. Although the Munster counties of Kerry and Cork are now considered the homeland of the clan, the original stronghold was more likely the province of Leinster. This is probably due to the westward migration of Murphys from Leinster in the 17th century. Murphy itself is an anglicization, and some have reverted to the Gaelic version Murchu. While Murphy is Ireland’s most common surname, held by over 50,000 people, there are now more Murphys living in the United States.

9 Rossi

The most popular surname in Italy, Rossi is believed to have come from the word rous (meaning “red”) to describe someone with red hair or a red complexion. The name is most common in northern Italy, where there were a great number of Celtic-speaking peoples before the Roman conquest in the first century BC and a slightly higher proportion of red-haired individuals even today. The popularity of the surname may have increased in the sixth century with the invasions of Northern Italy by red-haired Germanic Anglo-Saxons. Variations of the name include Russi, Russo, and Rosso, and it shows up in Spain and Portugal (which also had Celtic indigenes and invaders) as Ros and Rojo. Historically, there is a correlation between red hair and the presence of the surname in Italy, with the exception of Sardinia where both red hair and the surname Rossi are rare. Hair color descriptions also appear as nicknames in Italy, such as Biondi (“blond”), Bruni (“brown”), and Bianchi (“white”). One website disagrees with the standard etymology for the surname. According to the Clan Rossi site, the surname actually derives from the Eastern Scandinavian tribe known as the “Russ” or “Russii,” who also gave their name to Russia. However, there is little evidence that this etymology has been accepted by serious scholars.

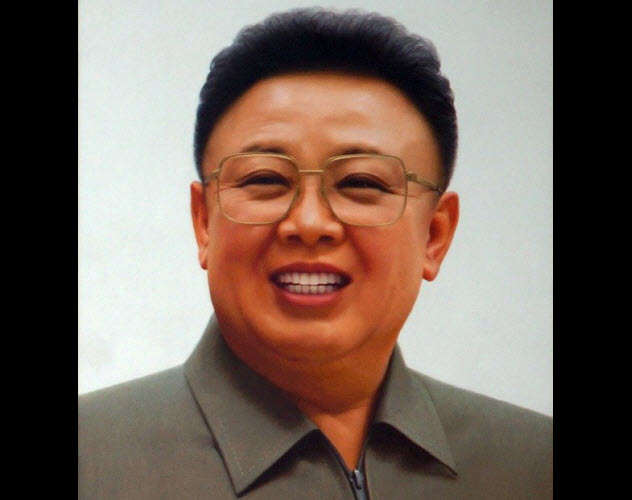

8 Kim

The most common surname in South Korea is Kim, held by one out of five people in a population of 50 million. Other common names in the country are Park and Lee, also held by a disproportionate number of people. These surnames were largely derived from Chinese surnames. For most of Korean history, surnames were reserved for the royal family and later the aristocracy, which explains why there is so little diversity in these names. Wang Geon, founder of the Goryeo Dynasty (918–1392), began to grant surnames to faithful subjects and government officials. Passing the gwageo civil-service examination was the only other way to gain social mobility and be granted a surname. Later, successful merchants were able to purchase surnames from bankrupt members of the aristocracy by buying a jokbo, a genealogy book, and adopting the surname. The name Kim has been the most common surname to emerge, with over 300 different origins throughout the country, and many clans named Kim were distinguished by their region of origin, such as the prominent Gyeongju Kim and Gimhae Kim clans. In 1894, the class system was abolished, and commoners began to adopt surnames, usually taking the name of their former master or a name in common usage. They usually chose the most common surnames: Lee, Park, and Kim. Today, the Kim clan is growing even more as it is the most common surname chosen for naturalizing immigrants from China, the Philippines, Thailand, and Mongolia. Published in the New Journal of Physics, research by Seung Ki Baek used statistical analysis to trace the history of the surname. Of the 50,000 Koreans who possessed surnames in 500 AD, he found that 10,000 used a variation of the Kim surname. The study determined that the number of people named Kim increased and decreased in proportion to the population—which grew and shrunk due to wars, earthquakes, famines, plagues, and fertility variations—while other surnames waxed and waned in importance over the centuries.

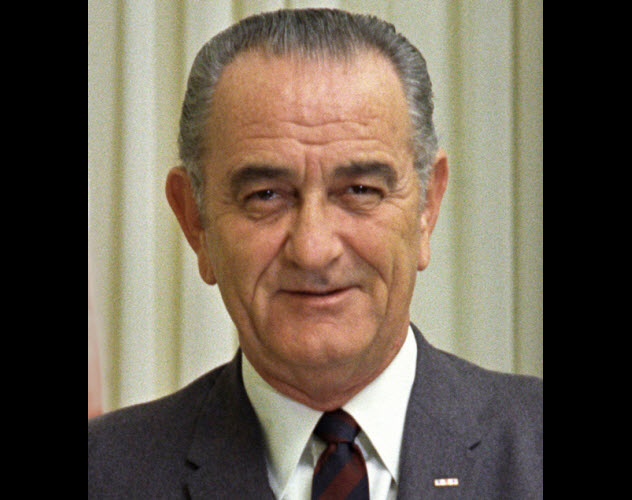

7 Johnson

An English patronymic name, Johnson literally means “son of John” (“gift of God”), deriving from the Latin Johannes, which came from the Hebrew Yochanan (meaning “Jehovah has favored”). Early Johnsons in England claimed descent from the Norman fitzJohns, while the first recorded use of the name was in 1287 in the name Jonessone. Variations on this name throughout Europe include Jones (Wales), Johnston and Johnstone (Scotland), Jonsson and Johansson (Sweden), Johansen and Johnsen (Norway), and Jorgensen (Denmark). Variations on the name have always been popular around Europe, being particularly linked with the Crusades. The first Johnson in the United States was a planter named John Johnson in 1622. One of the earliest Johnsons in the African-American community was a black slave named Antonio, who was brought to America in 1621 and eventually freed. He married a white woman and changed his name to Anthony Johnson. Many immigrants to the US from Scotland, Sweden, Norway, and Denmark also changed their names to better fit into their new culture, so Huber became Hoover and Nilsson became Nelson. This fact explains why the Johnson surname is the second most popular in the United States while only the ninth most popular in England. States like Minnesota with particularly large populations of Scandinavian descent boast a disproportionate number of Johnsons.

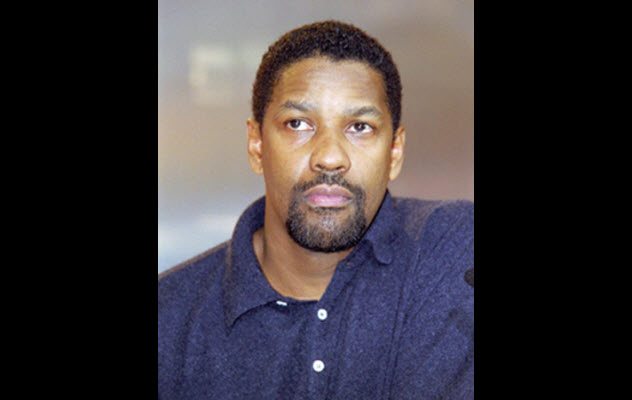

6 Washington

The most popular surname for African Americans is Washington, with a staggering 173 black Washingtons for every 10 white Washingtons. The 2000 US Census counted 163,036 Washingtons, of whom 90 percent were black. The reasons for this are deeply linked to the history of slavery. Before emancipation, slaves did not have their own surnames, and there is little to the myth that freed slaves adopted the surnames of their ex-masters. In fact, most chose their own surnames to assert their newfound freedom. Of the 12 US presidents that held slaves (eight while sitting in office), only Washington set his slaves free, leaving instructions in his will to do so after his wife’s death. Although his personal fortune was largely accumulated from his use of slaves, Washington was personally opposed to the institution on philosophical grounds. As his biographer Ron Chernow was quoted as saying on The Huffington Post, “Washington was leading this schizoid life. In theory and on paper he was opposed to slavery, but he was still zealously tracking and seeking to recover his slaves who escaped.” Through his will, Washington freed 124 slaves, with provisions for the younger black people to be educated or taught a trade and for the elderly to receive the care they needed. It is believed that many freed black slaves chose the name Washington as a way of affirming their status as free Americans. They were following the example of Booker T. Washington, who apparently chose his surname on a whim as a child. He had noticed that other children had surnames, and he had only been known as Booker all of his life. It is likely that he chose the name to show his respect for the first president and his devotion to his country. This was a common strategy, as can also be seen in the second most popular black surname in the United States: Jefferson.

5 Nguyen

An astonishingly common surname, Nguyen belongs to 40 percent of all Vietnamese people, including the overseas diaspora, accounting for 38 million out of 94 million people. This includes many Vietnamese and Vietnamese-American politicians, actors, entrepreneurs, and the inventor of “Flappy Bird.” Even Ho Chi Minh, the most significant figure in 20th-century Vietnamese history, was first known as Nguyen Sinh Con. The name originates from the Chinese surname Ruan, meaning a “stringed instrument,” but its popularity is linked to the trials and tribulations of Vietnamese dynastic history. In 1232, the ruling Tran Dynasty ordered members of the previous ruling family, the Ly, to change their name to Nguyen. This was done because the father of the founder of the Tran Dynasty was a Ly and because the Tran wanted to reduce any remaining public loyalty to the Ly by completely wiping out their name. Later, after the Tran Dynasty fell to the Ho Dynasty and their Ming Chinese allies, a genocidal campaign against the Tran reduced their numbers, forcing many to adopt Nguyen to survive. After the Ho came the Le Dynasty, who were also largely wiped out when the final Vietnamese dynasty, this time named Nguyen itself, came to power. The name Nguyen suddenly became prestigious, and many people changed their surnames to Nguyen for both survival and societal advancement. The Nguyen Dynasty also gave the surname as a reward to people who aided the state. While this plethora of Nguyens would seem to be a source of confusion, it isn’t so bad. In the Vietnamese media, it is considered acceptable to refer to politicians and prominent people by their given names rather than their family names. For example, Prime Minister Nguyen Tan Dung is usually called “Dung” or “Mr. Dung” in news reports.

4 Singh

The lion, called sinha in Sanskrit, is an important symbol in India. Some say that the early Aryan conquerors saw themselves as the “Lion People,” or Sinhala. Sinha led to Singh, a popular title and surname in northern India, which has a proud martial tradition. Historically, the Rajputs were compared with feline predators due to their warrior reputation, giving popularity to the name Singh, which also means “lion.” Some even combined feline predators for their names, such as Sher Singh (“Lion Lion”) and Bagh Singh (“Tiger Lion”). In India, surnames were invariably associated with the caste system. The 10th guru of the Sikh faith, Gobind Singh, sought to dismantle this system to create a unified Sikh identity, a community of “saint-soldiers.” At a historic gathering in 1699, the guru told his followers that all Sikh males were to adopt the surname Singh, while female Sikhs were told to adopt the surname Kaur, meaning “lioness” or “princess.” This was part of a process to create a Sikh community known as the Khalsa (or “pure”), in order to stand firm against their formidable Mughal enemies. The reputation of the Singhs as a powerful and unified body earned the respect even of their enemies. In the 18th century, Qazi Nur Muhammad, an enemy of the Sikhs, described them in poetic Persian: Singh is a title (a form of address for them). It is not just to call them “dogs” [his derogatory term for Singhs]. If you do not know the Hindustani language . . . the word Singh means a lion. Truly, they are like lions in battle. [ . . . ] Leaving aside their mode of fighting, hear ye another point in which they excel all other fighting people. In no case would they slay a coward, nor would they put an obstacle in the way of a fugitive. They do not plunder the ornaments of a woman. [ . . . ] They do not make friends with adulterers and housebreakers.

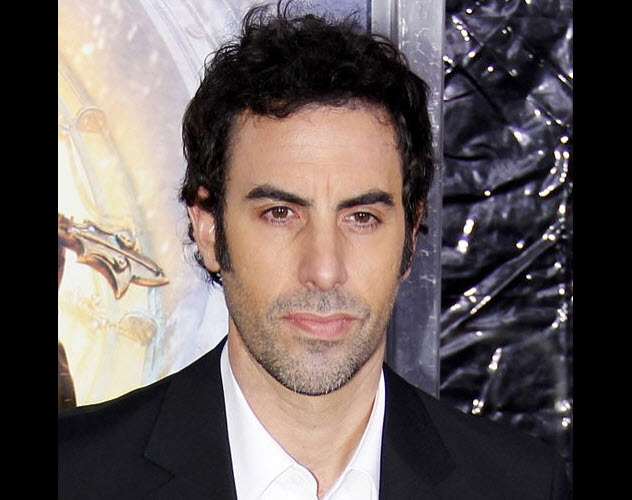

3 Cohen

One of the most common Jewish surnames is Cohen. Indeed, one school of thought divides Jews into variations on three surnames: Cohen, Levy, and Israel, the last of which in this case simply means “the rest of us.” The name Cohen is derived from the word kohein, Hebrew for “priest.” There are a number of variations on the surname, including Cohn, Kahn, Caen, and Kagan. One unusual variation is the name Katz, derived from the Hebrew kohein tzaddik, or “righteous priest,” which was apparently adopted due to similarity to the German word for “cat,” allowing Jews forced to adopt a German name to fly under the radar. Traditionally, Cohens are considered descendants of Aaron, the priest of the Temple in Jerusalem 2,000 years ago. In a religious sense, the Cohens are considered a clan rather than a family, and their descent from Aaron gives them certain privileges and responsibilities in Jewish religious life as well as restrictions like being unable to approach a dead body. With Cohens making up only around 2 to 3 percent of Jewish people, there is significant controversy over just how it is possible that so many Jewish people can claim descent from Aaron, as Jewish religious law states that Cohens cannot marry a new convert to Judaism. This religious law is active even today, such as in the 2005 case in Israel of Irina Plotnikov, a Russian immigrant to Israel who was blocked from marrying her fiance, Shmuel Cohen, by a rabbinical court. Even though she was recognized as being Jewish, her father was not Jewish, causing the court to rule that “she can be married in accordance with Jewish tradition, except to a Cohen.” However, some people distinguish between ancient and modern Cohens, such as 14th-century scholar Isaac ben Sheshet, who believed that the rights and responsibilities conferred upon modern Cohens were based on de facto acceptance and not strict adherence to Jewish law. Many Jewish legal scholars were suspicious of the purity of Cohen descent due to the long wanderings of the Jewish people during the Diaspora.

2 Li

Li, sometimes spelled Lee, is a popular surname accounting for around 7 percent of the Chinese population, followed closely by Wang and Zhang. Variations on the name are Yi in Korea and Ly in Vietnam. In early Chinese history, only the nobility possessed surnames. The ultimate origins of the Li name are clouded by various myths. According to legend, the name Li was first conferred on Gaotao, the grandson of mythical Emperor Zhuan Xu. Gaotao was the Regulatory Official for Law Enforcement, or li-guan, the equivalent of a modern judge. His title became the basis of the Li surname. Originally, the Chinese character associated with the Li name meant “justice.” Later, during the Shang Dynasty, a man named Li Zheng ran afoul of Emperor Zhou and was executed. His wife and son escaped to some ruins in the modern Henan province where they faced starvation and the emperor’s wrath. The wife fortunately came across some wild plums, or muzi, which allowed them to survive. They changed the Chinese character associated with the Li surname to a character that merged the two characters for muzi, both to show their appreciation and to elude the emperor. The “plum” character is still used for the Li family today. The popularity of the Li surname jumped significantly due to a Tang Dynasty policy called “surname bestowal,” which was designed to create fictive kinship relationships to aid stability for the regime. The founder of the Tang Dynasty, Emperor Taizong, had the birth name of Li Shimin. Therefore, bestowing Li onto valuable or prominent citizens helped to increase loyalty to the dynasty. Around one-third of known surname bestowals took place at the imperial court, where aristocrats vied for political influence. Another two-thirds were bestowed upon warlords and other martial clients who submitted to Tang authority. This even included non–Chinese clients among the Turk and Kirghiz peoples on the Chinese border, although this was the exception rather than the rule. The Li lineage had so much prestige that some borderland peoples like the Tangut continued to use the surname even after the fall of the Tang Dynasty.

1 Smith

Smith is an extraordinarily common name in English-speaking countries, ranked first in the United States, England, Scotland, Australia, and Canada. Smith was originally an occupational surname for someone who made or repaired metal objects, derived from the Saxon word smitan, meaning “one who smites or hammers.” Other occupational surnames such as Baker, Shepherd, Webster, and Chapman are also common but none with the dominance of Smith. Part of the reason was likely that “smith” was originally also applied to workers of wood as well as metal. Even soldiers could be called “War-Smiths” and poets “Verse-Smiths.” One of the most fascinating aspects of the name Smith is its utter classlessness. Historically, it has been common at all levels of British society. While every village in medieval England had a smith, who usually adopted their occupation as a surname, smiths were also one of the very first specialist classes, who enjoyed higher status and were taxed at a higher rate. Later, their numbers increased when compound surnames like Smithson and Combsmith were abbreviated. Smith was a neutral name belonging to no single class. As such, it became one of the most popular names in England. Similar patterns were present in Scotland, where smiths where ranked third behind the chief in tribal hierarchies, and Wales, where smithing was one of the three occupations a tenant couldn’t teach his son without permission (the others being scholarship and bardism). Despite the popularity of both the first name John and the last name Smith, the name John Smith is much rarer than statistics suggest for two reasons. In a cultural sense, John Smith is seen as a unimaginative placeholder, the name of an everyman with no intrinsic identity. Also, the name John is more common among Catholics, who have a cultural tendency to name their children after saints, so Johns are far more likely to have Irish, Italian, or Polish surnames. David Tormsen doesn’t have a common surname. Email him at [email protected].

![]()