They went on to achieve great things, whether that meant temporarily cross-dressing, adopting an alias, or impersonating a man for a long period of time until they reached their goals. This was often at great risk, too. Turns out it’s not such a man’s world after all.

10 Rena ‘Rusty’ Kanokogi

In 1959, Rusty Kanokogi entered the YMCA Judo Championship in Utica, New York. She cut her hair short, taped down her chest, and went on to win her fight. However, when she stepped up to collect her medal, the tournament organizer asked if she was a woman. When she replied “yes,” she was stripped her of the winning medal. Kanokogi said of the experience, “It instilled a feeling in me that no woman should have to go through this again.”[1] Her goal was for women’s judo to be considered an Olympic sport. In 1984, her dream began to come true at the Los Angeles Games when women’s judo became an exhibition sport. In 1988, when the Summer Olympics were held in Seoul, South Korea, it attained medal status. Considered the mother of women’s judo, Kanokogi died from complications of cancer at age 74 in 2009. One year earlier, the Japanese government had awarded her the Order of the Rising Sun, Japan’s highest honor for a foreigner.

9 The Bronte Sisters

Sisters Charlotte, Emily, and Anne Bronte published their collection of poetry Poems by Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell under male pseudonyms in 1846. The following year, the novel Wuthering Heights was published under Emily’s pen name, Ellis Bell. In 1847, Jane Eyre was also published under Charlotte’s pen name, Currer Bell, and Agnes Grey was published under Anne’s pen name, Acton Bell. In the preface for the 1910 edition of Wuthering Heights (published posthumously following Emily’s death in 1848), Charlotte explained why the sisters decided to adopt male names for their published works. She said: Averse to personal publicity, we veiled our own names under those of Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell; the ambiguous choice being dictated by a sort of conscientious scruple at assuming Christian names positively masculine, while we did not like to declare ourselves women, because—without at that time suspecting that our mode of writing and thinking was not what is called “feminine”—we had a vague impression that authoresses are liable to be looked on with prejudice.[2] After receiving generous critical reviews for their work, the Bronte sisters began publishing under their own names. They remain some of the most important authors in the history of literature.

8 Joan Of Arc

Joan of Arc (aka “The Maid of Orleans”) was considered a heroine during her 19 years of life from 1412 to 1431. Born into a peasant family in northeast France, she believed that God had given her a mission to save France from its enemies and that Charles VII should be the rightful king. At age 16, she disguised herself as a man and journeyed across Chinon with her small band of followers. She managed to convince Charles VII that she was a messenger from God and would see him installed as the ruler of France. Against the advice of his counsel, Charles VII granted Joan an army which she led to Orleans. In 1430, as she attempted to defend Compiegne from an assault, Joan was thrown from her horse and held captive by the Burgundians. She was held on 70 charges, including dressing like a man and witchcraft. Following a signed confession, she was burned at the stake the very next year.[3]

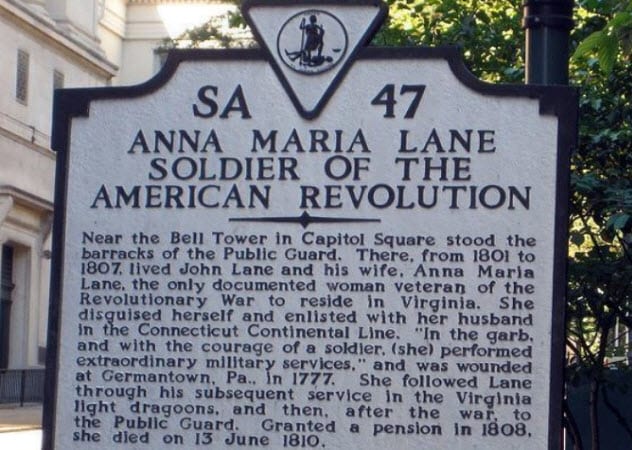

7 Anna Maria Lane

In 1776, Anna Maria Lane enlisted in the Continental Army. Typically, women joined as cooks, nurses, or laundry assistants. They did not enlist as soldiers. However, Lane desired to fight alongside her husband, John, so she disguised herself as a man. That way, she could serve in New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Georgia. Her real identity would easily have gone undetected as 18th-century soldiers did not bathe often and were known to sleep in their uniforms. Historian Joyce Henry confirmed: As far as enlistment, there are no physicals when one enters the army in the 18th century. One must have front teeth and an operating thumb and forefinger so one may be able to reach in, grab a cartridge, tear off the paper, and be able to successfully load your musket.[4] During the Battle of Germantown near Philadelphia in 1777, Lane was wounded but she survived. It’s unknown when she was detected as a woman, most likely when she was injured. However, she successfully managed to stay by her husband’s side throughout the war. Her bravery was rewarded with $100 a year for life in recognition of her service. She died in her mid-fifties on June 13, 1810.

6 Deborah Sampson

Deborah Sampson became the only woman to earn a full military pension for fighting during the American Revolutionary War. Formerly a teacher, she disguised herself as a man named Robert Shurtleff and joined the Patriot forces in 1782.[5] During her service, she led about 30 infantrymen on an expedition, successfully captured 15 men, dug trenches, and faced cannon fire. For almost two years, her real identity remained undetected until she became ill and was taken to the hospital unconscious. In 1783, she received an honorable discharge and toured as a lecturer. She retold her experience while often dressed in her full military regalia. After her death in 1827 at 66 years old, her husband petitioned Congress for spousal support that would have been awarded to a female widow without question. Congress agreed to give him spousal pay because there was “no other similar example of female heroism, fidelity and courage” like Sampson. However, her husband died before receiving any of the money.

5 Joanna Zubr

Polish soldier Joanna Zubr hid her identity from the soldiers who fought beside her in the Napoleonic Wars. In 1808, Zubr joined the army with her husband, Michal Zubr. She was eventually promoted to sergeant. Their unit was later renamed the Greater Polish Division and took part in Napoleon’s invasion of Russia. During their retreat, she was separated from the division. But Zubr managed to escape Russian territory on her own and return to Poland safely. Reunited with her husband, they were unable to return to Austrian-occupied and Russian-held parts of Poland. Instead, they settled in Wielun where she lived the rest of her days. She became the first woman to receive the Virtuti Militari medal, the highest Polish military honor. This made her the first woman in history to receive an award for bravery in battle. In 1852, she died during a cholera epidemic at about 80 years old.[6]

4 Maria Quiteria De Jesus

In 1822, Maria Quiteria ran away to join the troops in the Brazilian Army. She cut her hair, dressed in masculine clothes, and was able to avoid detection until her father—who had refused her request to join the army – discovered the truth. Despite her father’s knowledge, she did not abandon the army and her presence was welcomed by Major Silva y Castro due to her skill in the battle.[7] From October 1822 until June 1823, Maria Quiteria ambushed her enemies in the province of Bahia by luring them to a nearby camp where she would turn on them with her hidden bayonet. In August 1823, she was granted the rank of lieutenant by Emperor Pedro I—an unheard-of accolade for a woman. In 1953, 100 years after her death, the Brazilian government hung a portrait of Maria Quiteria on the wall at their military headquarters as a national honor.

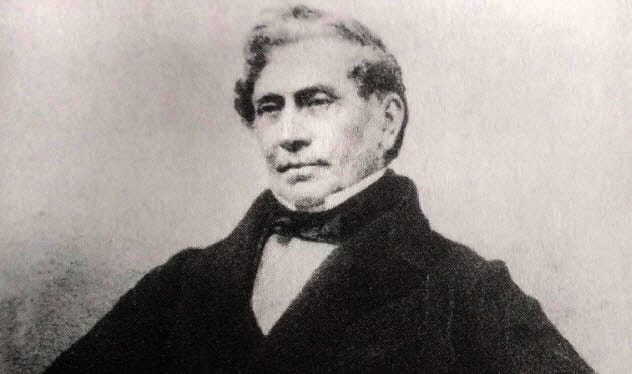

3 James Barry

Military surgeon James Barry served as an Inspector General in the British Army. He was in charge of the military hospitals and vastly improved conditions for patients during his career. Barry was also the first surgeon in South Africa to perform a Cesarean section in which both the mother and child survived. Born Margaret Ann Bulkley, Barry’s real identity was only discovered after his death in 1865. As a maid prepared his body for the funeral, the sensational discovery was revealed. The British Army was so shocked that they blocked access to all Barry’s papers until the case was reopened by historian Isobel Rae in the 1950s. One historical figure who was not a fan of Barry was Florence Nightingale, the founder of modern nursing. She wrote of her experience meeting the surgeon: He kept me standing in the midst of quite a crowd of soldiers . . . every one of whom behaved like a gentleman while he behaved like a brute. After he was dead, I was told that [Barry] was a woman . . . I should say that [Barry] was the most hardened creature I ever met.[8]

2 J.K. Rowling

Harry Potter author Joanne Rowling, known famously around the world as J.K. Rowling, revealed that she had decided while still unpublished to drop her first name from her books on wizardry and witchcraft to better appeal to a young male audience. Harry Potter went on to become the best-selling book series in history. The titles have been translated into over 60 languages. In 2013, Rowling decided to switch to a male pen name again for her crime fiction novel The Cuckoo’s Calling. She wanted to “take my writing persona as far away as possible from me.” Rowling published the book under the name, Robert Galbraith, explaining, “I successfully channeled my inner bloke!” Initially, editor David Shelley read it without knowing that Rowling was the author. Shelley later said, “I never would have thought a woman wrote that.” Galbraith’s identity did not stay secret for long because a friend of one of her lawyers leaked the news. Subsequently, the book became another literary hit for Rowling.[9]

1 Kathrine Switzer

Runner Kathrine Switzer made history as the first woman to run the Boston Marathon in 1967. At that time, females were banned from competing. She had applied to compete in the race as a man. After it was discovered that a woman was running the 42-kilometer (26 mi) race, officials grabbed at her to try to stop her. Switzer recalls: Before I could react, he grabbed my shoulder and flung me back, screaming, “Get the hell out of my race, and give me those numbers!” Then he swiped down my front, trying to rip off my bib number, just as I leaped backward from him. I was so surprised and frightened that I slightly wet my pants and turned to run. She added, “I knew if I quit, nobody would ever believe that women had the capability to run 26-plus miles. If I quit, everybody would say it was a publicity stunt. If I quit, it would set women’s sports back. My fear and humiliation turned to anger.” In 1972, women were officially allowed to enter the marathon.[10] Cheish Merryweather is a true crime fan and an oddities fanatic. She can either be found at house parties telling everyone Charles Manson was only 157.48 centimeters (5’2″) or at home reading true crime magazines. Follow her on Twitter: @thecheish. Read More: Twitter Facebook