Often, when historians or biographers describe a person’s life, the prominent deeds of that person overshadow the relatively minor details that occurred before or after that. Thus, even major changes in a famous person’s political philosophy are overlooked.

10Salvador Dali

Although there are numerous critical opinions on the value of Dali’s art, his work is likely one of the most recognized by the public. Although he wasn’t a politician or a political activist, his shifting viewpoints and statements caused much controversy. Despite that, a number of people considered him an apolitical person. In the 1930s, Dali fell out with the surrealists as they joined left-wing anarchism and Stalinism. Dali refused to openly condemn the growing fascist movements. After his expulsion from the group, he moved to the United States during World War II. However, he completely upset the art world when he declared support for Franco. Later, having turned to the Catholicism of his youth, Dali returned to Spain. After the restoration of the monarchy, King Juan Carlos even gave Dali a title of nobility. Due to politics and artistic judgment, Dali’s reputation with the art establishment was at its nadir, but his work remained popular with public.

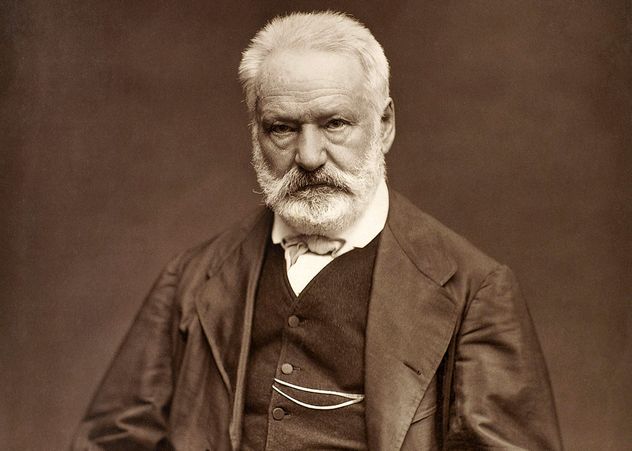

9Victor Hugo

Victor Hugo was a prolific creative writer. Although he wrote poetry, drama, and fiction, people today mainly recognize him as the author of The Hunchback of Notre Dame and Les Miserables. In his time, people also recognized Hugo as a social and political critic. In his later life, Hugo was one of France’s foremost republican and anticlerical advocates. Earlier in his life, however, he displayed a willingness to support a parade of political movements. In his young adulthood, Hugo was strongly attracted to the Bourbon Monarchy of Louis XVIII. Many of Hugo’s youthful poems reflect this sentiment. However, with the ascent of Charles X and the censorship of his work, Hugo fell out with the monarchy. In the 1830s, he then took up the cause of Bonapartism. Initially, Hugo supported Napoleon’s son. But the son died, and following the 1848 revolutions, Hugo took up the cause of Napoleon’s nephew, Louis-Napoleon, who became Napoleon III. As Napoleon III became more dictatorial, Hugo heartily criticized his reign. Because of this criticism, Hugo was an exile until Napoleon III was overthrown in 1870. On his return, Hugo supported each successive republican government until his death.

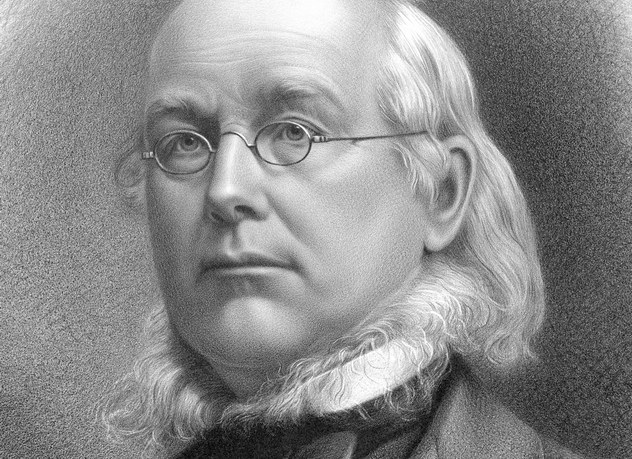

8Horace Greeley

Unfortunately for Greeley, some people would’ve considered him the “neckbeard” of his age, if they had such a term. As an influential journalist and newspaper editor, he took up a number of causes—some popular, some not. Greeley wrote and spoke against liquor, tobacco, capital punishment, gambling, and prostitution. In the antebellum period, he was one of the foremost opponents of slavery. However, from the Civil War onward, Greeley pursued an erratic course. He generally sided with the Radical Republicans on issues of civil rights. But he opposed Lincoln’s renomination and posted the bail for Jefferson Davis after the Civil War. Disenchanted with the Grant administration, Greeley joined the Liberal Republican Party. In 1872, he was the nominee not only for that party but for the Democratic Party as well, which ran primarily on a platform of reform, lower tariffs, and a softer Reconstruction policy. The unsuccessful campaign was so brutal that Greeley died during the election.

7Samuel Taylor Coleridge

While people recognize Samuel Taylor Coleridge for his poetry, very few people outside academic circles consider his social-political work. His later political criticism, On the Constitution of the Church and State, influenced some of the thought of later European conservatism. However, looking at Coleridge’s early life, one would be surprised to see his political thought take this trajectory. Like most Romantic poets of the late 18th century, Coleridge was interested in numerous reforming ideas. He opposed the slave trade and followed the progression of the French Revolution. He wanted the liberal ideals expressed during that event to spread throughout Europe, including his native England. But he was horrified and disappointed by the tyranny and bloodshed that followed the initial hope. Therefore, along with fellow poet Robert Southey, Coleridge decided to form a “pantisocracy”—a small, rural, communal government, where “destructive societal values” wouldn’t enter. They found wives, but domestic turmoil, along with Coleridge’s lack of practicality, led to the collapse of the experiment. Following this, Coleridge gave up utopian schemes but proposed the ideal of England as a traditional, organic nation as expressed in On the Constitution of the Church and State.

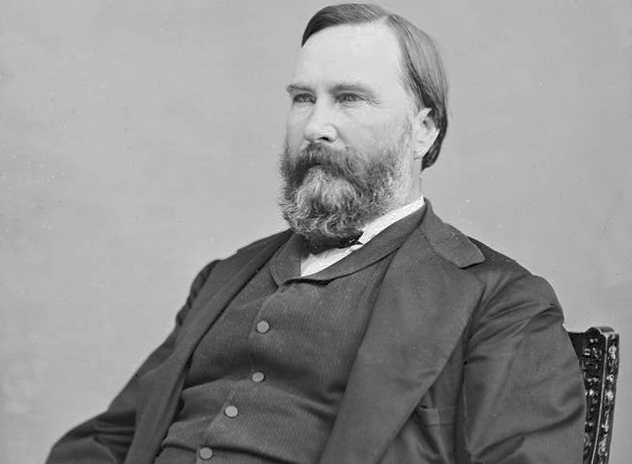

6James Longstreet

A number of historians consider him one of the most competent commanders of the Civil War. As a man from the Deep South, there was likely no question whether he would side with the secessionists and join the Confederate cause. It also helped that Longstreet spent much of his childhood in the home of an uncle who strongly favored the doctrines of John C. Calhoun. Although Longstreet was not a fierce supporter of slavery, he acquiesced to the Confederate States of America’s policies during the war, some of which are reprehensible to modern tastes. After the war, Longstreet did something that shocked most of the South: He became a Republican and endorsed Ulysses S. Grant for president. As a result, many Southerners viewed Longstreet as a scallywag. As a supporter of Grant, he endorsed the Reconstruction policies issued by Congress and received a number of political appointments. In the eyes of many unreconstructed ex-Confederates, Longstreet’s worst action was in New Orleans, where he was given command of African-American troops and led them against the Redeemers who were disrupting the voting process. Because of these actions, critics even slandered his wartime service, until modern reappraisal and the publication of Michael Shaara’s The Killer Angels.

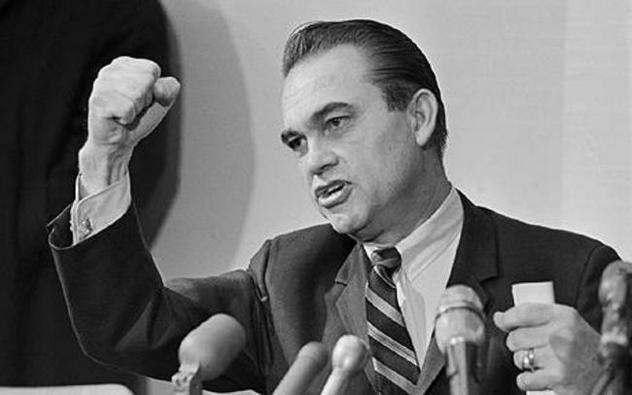

5George Wallace

“Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” This is the phrase that people likely remember when someone mentions the name of George Wallace. During the 1960s, he was a die-hard supporter of segregation. Wallace, elected governor of Alabama in 1962, uttered those infamous words at the conclusion of his inaugural address; the election was run on a platform of racial segregation, and he had the backing of the Ku Klux Klan. However, before the election, Wallace didn’t always have the reputation as a bigot. Wallace had served two terms in the Alabama State Legislature. He then decided to enter the 1958 gubernatorial race. In that election race against John Patterson, Wallace not only declined the endorsement of the Ku Klux Klan but refused to make segregation a campaign issue. The result was that he lost. Wallace thus decided that he had to give the voters what they wanted. Later, Wallace again changed his viewpoint and mellowed on the issue of race. After the 1972 assassination attempt on his life and a conversion to born-again Christianity, Wallace even apologized for his previous actions. As a result, he won his fourth gubernatorial term largely due to the support of the African-American voters.

4Strom Thurmond

Many people today know Thurmond primarily as another staunch defender of segregation in the mid-20th century who fathered a daughter—Essie Mae Washington-Williams—with an African-American house cleaner. In 1948, Thurmond ran as the Dixiecrat candidate opposing both the Democratic and the Republican parties on the issue of segregation. During his time as a Senator in the 1950s–1960s, Thurmond opposed the civil rights bills proposed in Congress. Then a change happened in the late 1960s. Thurmond not only stopped running on segregation issues, but he began courting African-American voters. In 1971, he even appointed the first African-American senatorial staffer in South Carolina—Dr. Thomas Moss. In 1983, Thurmond supported the making of Martin Luther King Jr. Day. Thurmond’s popularity in the state and large vote totals during later elections were due to both black and white voters’ support. Interestingly, people viewed Thurmond as a moderate in racial issues in his early political career, just as they had viewed Wallace.

3Winston Churchill

Churchill is mainly known for his strident opposition to Nazism in the 1930s and 1940s and his similarly strong opposition to Communism after World War II. As the son of a prominent Conservative Party member, defender of the British Empire, and Prime Minister in opposition to the Labour Party, Churchill is recognized by most people as being a traditionalist figure. However, during the first decade of the 20th century, Churchill was a radical liberal. During this period, Churchill switched from the Conservative Party to the Liberal Party. Under the influence of Lloyd George, Churchill advocated for pensions, unemployment insurance, public health care, and reform of the House of Lords. Churchill likely would’ve continued this advocacy, but troubles in foreign affairs—which eventually led to World War I—turned his attention to other matters. After the war, Churchill switched back to the Conservative Party and proposed other reforms—but not as stridently as in his youth.

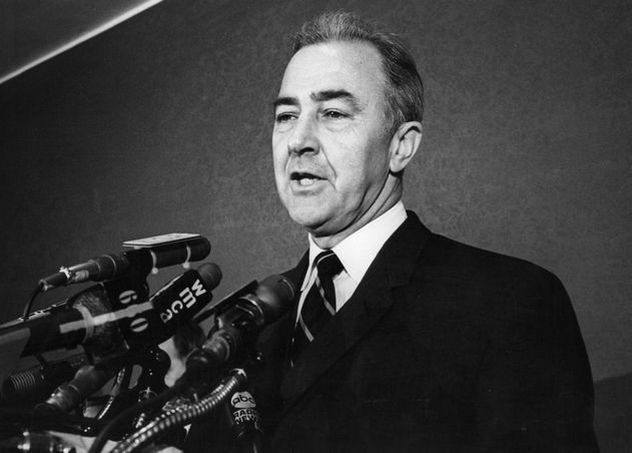

2Eugene McCarthy

“Get clean for Gene!” That was the rallying call for many who supported the presidential ambitions of Eugene McCarthy. A number of individuals cut their hair or shaved their beards before going around the nation to campaign for the most prominent anti-war candidate in the 1968 presidential election, following the assassination of Robert Kennedy. McCarthy had served a decade each in both the House and Senate, where he solidified his reputation as a liberal. However, McCarthy was still a relatively obscure politician, until he challenged President Johnson’s nomination on the Vietnam War issue. In the commotion of the 1968 primaries, he lost to the eventual Democratic nominee, Hubert Humphrey. McCarthy unsuccessfully ran for the Democratic nomination two more times. His next move in 1980 surprised and shocked many people. McCarthy endorsed Ronald Reagan. People knew that the Carter administration had disenchanted McCarthy from Democratic politics, so some thought that he might endorse Anderson (a liberal Republican-turned-independent), Ed Clark (the Libertarian candidate), or Barry Commoner (an environmentalist). Although McCarthy wasn’t enthusiastic, he believed that the proposed economic and foreign policies of Ronald Reagan were sounder than any of the other platforms. Afterward, McCarthy tried to continue to run in politics, often as an independent. He never again had as much success as in that moment in 1968.

1Hillary Clinton

The current front-runner for the 2016 Democratic presidential nomination wasn’t always a Democratic standard-bearer. Clinton’s teenage and early college years show quite a difference. Influenced by her father and her high school history teacher—who encouraged her to read Barry Goldwater’s Conscience of a Conservative—Clinton described herself as a “Goldwater Girl.” As a member of the Young Republicans, Clinton said that she liked Goldwater “because he was a rugged individualist who swam against the political tide.” She thus campaigned for Goldwater, who was defeated in a landslide by Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964. Clinton’s political viewpoints gradually changed when she enrolled in Wellesley College. By the time of the 1968 election, Clinton became a fervent supporter of Eugene McCarthy, the Democratic anti-war candidate. Clinton still hadn’t switched completely to the Democrats. During the same time, she interned for Gerald Ford, the Republican leader of the House, and worked for Nelson Rockefeller, the GOP presidential nominee. It was in law school that Clinton transformed completely into a liberal Democrat while working with her future husband on the failed McGovern campaign. Christopher Fried is freelance writer and a formalist poet. He can be found at www.christopherfried.com and on various social media outlets.