A lot of the time, interspecies sex is pretty boring. Two unrelated animals find one another by mistake, and nothing much comes of it. Sometimes, though, the story gets more disturbing. In some cases, the two sets of genitals don’t fit together, and the sex causes physical injury. In other cases, it is part of a calculated deception, where one partner stands to benefit and the other loses out. In still other cases, the sex is deliberately violent and deliberately horrible and seems to make no sense at all. Here are 10 such stories taken from the natural world.

10Genital-Stabbing Flies

The penis of Drosophila yakuba, a fruit fly, is equipped with two spines. During sex, the male inserts these spines into a pair of pockets present in D. yakuba females. A closely related fly species, D. santomea, lacks this spine-pocket system. When a D. yakuba male has sex with a D. santomea female, the male has nowhere to put his spines. So he just stabs the female with them. The result is two wounds, set side by side. Without these pockets, the D. yakuba male also has trouble orienting himself properly. Often, he ends up ejaculating on the female’s outside, or on himself. This leaked semen creates a new problem. As it hardens, the semen glues the two insects together. After sex, the two partners must struggle hard to detach themselves.

8Aggressive Worm Sperm

In the nematode worm Caenorhabditis nigoni, females mate with multiple males. Sperm competition is fierce, and sperm have evolved to be very aggressive. In a related species, C. briggsae, reproduction is very different. Most worms are hermaphrodites who fertilize their own eggs. So sperm don’t need to be aggressive. In a 2014 paper, scientists paired C. nigoni males with C. briggsae hermaphrodites. The results were dramatic. And horrible. Over time, C. nigoni females have evolved defenses against the aggressive C. nigoni sperm. But the C. briggsae hermaphrodites don’t have any. In their bodies, the C. nigoni sperm wreaked havoc. Often, it escaped the uterus and penetrated other parts of the body, something like a cancer. After exposure to the C. nigoni sperm, the C. briggsae hermaphrodites’ life span was reduced, as was their fertility. In some experiments, the C. briggsae hermaphrodites seemed able to anticipate this harm. When paired with C. nigoni males, they could be observed crawling in the opposite direction, as if trying to get away.

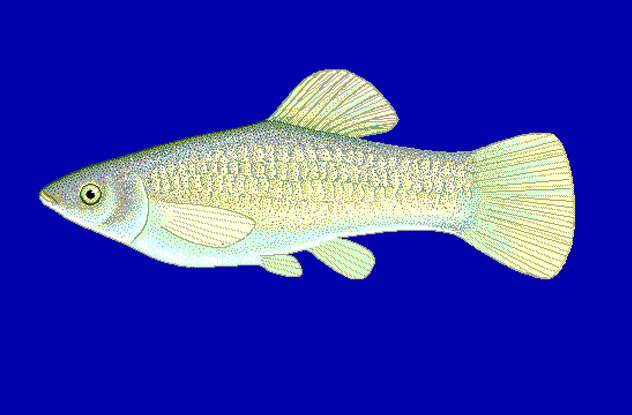

7Cutthroat Trout And Rainbow Trout

Sometimes, one species has so much sex with a second species that all of its offspring are hybrids. Once that happens, it’s all over. Species one is genetically absorbed by species two, and it ceases to exist. It’s called extinction by hybridization. As methods of extinctions go, it’s probably the best kind—way better than being hunted to death, for example. But it’s still unfortunate. This danger now threatens the cutthroat trout, native to Montana. With the rainbow trout, a non-native species, the cutthroat has bred for many generations, producing many mixed-species fish. Now, few pure populations remain. On one level, the success of these mixed-species fish doesn’t make sense. Purebred cutthroats actually have more offspring than mixed-species fish. Set in competition, head-to-head, the pure cutthroats should be winning out. So, why is this happening? Part of the answer may have to do with simple entropy. Once you start mixing things, it’s really hard to unmix them. Combine red and blue paint to make purple, and you can’t get the red paint back again. Same thing with fish DNA. Another factor is this: Hybrids may travel to more distant locations when they reproduce than purebreds do. This may help their genes to spread more rapidly. This problem has its roots in the 1880s, when rainbow trout were first introduced into Montana’s rivers. Little could it have been predicted, at that time, that these new fish would serve as a terrible sexual temptation for the native cutthroats—one that, a century on, would come to threaten the cutthroat’s very existence.

6Beetles With Mismatched Genitals

Two beetles, Carabus maiyasanus and C. iwawakianus, live together on the Japanese island of Honshu. In both species, the penis is equipped with a special knob called the copulatory piece. During sex, the male inserts this piece into a specialized offshoot of the female’s vagina, called the vaginal appendix. In C. maiyasanus, the copulatory piece and the vaginal appendix are longer and thinner. In C. iwawakianus, they are shorter and thicker. When the two species have sex, these differences can have violent consequences. For females of both species, the mismatch can cause the vagina to rupture, later leading to death. For C. maiyasanus males paired with C. iwawakianus females, the copulatory piece can also fracture, likely causing sterility. Interestingly, the two beetles have absolutely no inhibitions about having sex with one another. When given a choice, they pair off with a mate from the other species just as often as they do with a mate from their own species. The genital mismatch, then, seems to serve as an after-the-fact way to limit hybridization. Beetles who try it are more likely to die or to be rendered sterile. Hybrids still happen. But they’re rarer than they would be.

5Spadefoot Toads

Toads spend the first part of their lives in the water. As tadpoles, they have gills and tails, adapted to swimming. Only later, at metamorphosis, do they develop lungs. In some environments, water collects only in shallow puddles, which can dry up suddenly. In these environments, the length of the tadpole stage is very important. To survive, a young toad must complete metamorphosis before the water goes away. This problem affects the Plains spadefoot toad, which lives in the southwestern United States. To solve this problem, the Plains spadefoot toad has adopted an unorthodox strategy. It involves having sex with a second species, the Mexican spadefoot toad. Mexican tadpoles develop faster than Plains tadpoles, while Mexican-Plains tadpoles develop at an intermediate rate. Where water is limited, hybrid tadpoles are more likely to survive than purebred Plains tadpoles. Plains spadefoot females apply this strategy selectively. When times are good, they prefer males of their own species. During drought, though, this preference goes away. Many females choose Mexican spadefoot mates and produce hybrid young. It isn’t an ideal outcome. Mexican-Plains hybrids don’t make very good specimens. Many hybrid males are sterile, and hybrid females produce fewer eggs. But hybrid offspring are better than dead offspring. So, when times are bad, Plains spadefoot females settle for that.

4Violent Bedbugs

Bedbugs engage in a violent sex act called traumatic insemination. With his sharp genitalia, the male makes a hole in the female’s abdomen. Then, he ejaculates into the wound. Though sustaining stab wounds during sex is tough on the female, within a species, evolution places some limits on the deadliness of this practice. When bedbugs mate outside of their species, however, the damage can be more severe. In a 1989 paper, scientists looked at mating between two bedbug species, Cimex hemipterus and C. lectularius. In this paper, the scientists showed that interspecies sex is especially harmful for C. lectularius females. After sex with C. hemipterus males, C. lectularius females are less fertile and don’t live as long. The cost to C. lectularius females, as a result of interspecies sex, may limit where C. lectularius can live. Areas where C. hemipterus already has a foothold may be difficult to colonize. For C. hemipterus, in contrast, interspecies sex may be a good strategy. With it, it can harm rival bedbugs and secure more resources for itself.

3Ants That Steal Sperm

In ants, there are two kinds of females. Most are sterile workers. Other females are queens. The queens’ job is to make baby ants—lots and lots of baby ants. In ants, reproduction is weird in another way as well. It proceeds according to a system called haplodiploidy. In it, females develop in the normal way, with both a mother and a father. Males, though, develop from unfertilized eggs. They have only mothers. A male ant, in turn, can produce only daughters. If he is to be genetically successful, at least one of these daughters must be a queen. If he sires only workers, he will have no grandchildren. Ant colonies are competitive. To press their own advantage, they can commit acts of terrible violence. In Pogonomyrmex species, one competitive tactic involves interspecies sex. For a Pogonomyrmex male, interspecies sex is a terrible mistake. After ejaculation, his sperm will be used to make sterile hybrids, which will serve as workers for the competitor species. For the ant queen, in contrast, this sex works out great. Not only does she drain her competitors’ sperm reserves, but she also gets more workers. Win, win. This interspecies conflict, queens vs. males, plays out during the mating season. Sex, in both species, is a big orgy. In the confusion of it, it is not uncommon for a male of one species to begin copulating with a queen from the other, completely by accident. Only later, mid-coitus, will the mistake begin to dawn on the male. So he’ll try to pull away. But the queen won’t let him. In response to his struggles, she will only clutch him harder, forcing him to ejaculate all of his precious sperm. Only later, when his testes are empty, will the queen release him. Afterward, he will be left drained, a genetic failure.

2Seals That Assault Penguins

In humans, non-consensual sex is called rape. In animals, the preferred term is “forced copulation.” On Marion Island, north of Antarctica, scientists have studied an example of forced copulation occurring between two species. The aggressor is a mammal, the Antarctic fur seal. This victim is a bird, the king penguin. During an attack, a male seal chases a penguin, forces it down, and then initiates sex. Every few minutes, the seal stops to rest, while continuing to hold down its victim. Birds, unlike mammals, have a single opening, called the cloaca, which doubles as the genitals and anus. After being assaulted by a seal, one penguin was observed to bleed from this opening. After the seal left, this blood attracted predatory birds, which the penguin was forced to fight off. During another attack, the seal eventually left off having sex with the penguin and then just killed and ate it. Why the Antarctic fur seal might be committing these assaults is unclear. It may, though, be an act of sexual frustration. Young males, unable to find a mate within their own species, may have instead turned to penguins. The behavior may also be learned. The first seal-on-penguin assault may have been a random act. Other seals, though, may have observed it. Liking what they saw, they decided to try it themselves. Then, like a fad, the practice continued to spread. It is scientifically unfashionable to cast moral judgments on animals. But it’s hard to feel much affection for the Antarctic fur seal, knowing how it treats penguins.

1Otters That Assault Seals

In Monterey Bay, California, scientists have studied another example of forced copulation. This time, the victim is a second species of seal, the harbor seal. The aggressor is the sea otter. Watch this video on YouTube Male sea otters engage in violent sex—so violent, in fact, that female otters don’t always survive it. When sea otters have sex with harbor seals, the results are at least as grim. The otters’ preferred targets are juvenile seals, mostly seal pups. In a 2010 paper, scientists performed autopsies on several of these victims. They documented a range of injuries. There were wounds on the seals’ faces, caused by biting. Other wounds—more horrible—had been inflicted by the otters’ penises. The vaginas of many of the female seals were cut and bloody. The anuses of several of the seals had also been punctured, causing feces to leak into the body cavity. Death was no impediment to the otters’ pleasure. Long after their victims had died, the otters would continue to have sex with them. It is difficult to make sense of this behavior. As with the Antarctic fur seals, it may be the action of sexually frustrated males. Otters are polygynous. In otter societies, a few males mate with most of the females. This leaves most males unpartnered. A recent uptick in mortality, affecting female otters disproportionately, has made this problem worse. There is another disturbing part to this story. Two of the otters committing these assaults had been previously rescued by conservationists. At the time, no doubt, these rescues had seemed like good deeds. After getting their lives back, though, the otters went on to wreak havoc on young seals. Describing sea otters as “depraved” isn’t very scientific. On a purely personal level, though, it’s probably okay to dislike them. Rachel Rodman writes about hybrids, chimeras, and interspecies testicle transplants. You can read more here.