That was the day that World War II veteran Howard Unruh picked up his gun, strolled out into his neighborhood, and ended 13 lives. The incident became known as the Walk of Death, and it changed our understanding of mass violence forever. Although the US had suffered mass shootings as early as the 18th century, none had ever been so meticulous, deranged, or senseless as Unruh’s walk. It was the first truly modern mass shooting, and it set the template for every horrific crime that was to come.

10 A Premeditated Massacre

Mass shootings frequently occur during moments of hot temper. The Waco biker shootout of 2015, which killed nine people and injured 18, started over a parking dispute. However, when most of us think of mass shootings as a phenomenon, we picture premeditated affairs, like Columbine and Aurora. It was in this area that Howard Unruh had a modern outlook. He knew exactly who he wanted to kill. A polite, quiet, 28-year-old man, Unruh’s sedate outer appearance masked a mind festering with anger, paranoia, and jealousy. A combat veteran, he’d returned to his hometown of Camden, New Jersey, after the war, convinced that his Cramer Hill acquaintances were out to get him. We know this because by 1949, he’d begun to keep meticulous lists of those who had “wronged” him. A typical entry would list someone like Mrs. Cohen, the wife of the local druggist, telling him to turn down his Wagner records five times. To Unruh’s disturbed mind, these were unforgivable infractions. Unruh had a tendency toward list-making (a sure sign of psychopathy). During the war, he made detailed notes on every German soldier he killed, describing the conditions of their bodies. Now, that same hobby was blurring into his hometown life. As 1949 rolled on, Unruh’s lists became longer and longer. He began to identify people he wanted to kill and spent his free time practicing his shooting skills. As the year shifted into a sweltering summer, he began to make concrete plans, marking certain names with “retal”—short for “retaliate.”

9 The Final Trigger

In the aftermath of any violent tragedy, it can be tempting to wonder why no one noticed anything was wrong. In Unruh’s case, it wasn’t for lack of speculation. Neighbors all knew that the shy man on their street had a dark secret. Local children bullied him for it. Only, it wasn’t Unruh’s carefully hidden psychopathy they detected; it was his homosexuality. Unruh had been in the closet for nearly his entire life. In 1949, admitting that you were gay wouldn’t just get you ostracized; it could get you thrown in prison. Immediately after the war, Unruh wed a woman but seemingly felt only disgust at the thought of consummating their marriage. When the marriage imploded, he finally found the courage to indulge his sexual desires, if not always successfully. The night before his infamous walk, Unruh had arranged to meet a man at a popular gay theater, where sex took place between gangster features and Barbara Stanwyck dramas. The man never showed. It was this failed connection that seems to have pushed Unruh to edge of the precipice. After six hours waiting in the theater, his mind stewing, he returned home in a foul mood. As he entered his mother’s ground-floor apartment, he saw that the new fence he’d built between their property and the Cohens’ had been removed. Strange as it may seem, this was the moment that Unruh decided to act upon his dark fantasies. The Cohens were his number-one enemies, taking up page after page in his book of infractions, and this was apparently one slight too many. Unruh went inside, took out his German Luger P08, loaded it, and waited for morning. Sunrise brought the bloodiest day in Camden’s history.

8 The Walk Begins

At 8:00 AM on September 6, Freda Unruh woke her son from an uneasy doze with a breakfast of fried eggs and milk. For 10 minutes, it seemed as though that Tuesday would be the same as any other. Then, Howard finished his breakfast, went down to the basement, and came back with a wrench. He raised it high above his head, as if intending to kill his mother. Freda later said that his face was blank, like he didn’t recognize her. By talking calmly, she managed to keep him in place while she backed out the door and ran to a friend’s house. When the shooting started minutes later, Freda knew exactly what had happened. With his mother out the picture, Unruh grabbed a knife, some tear gas, and his Luger and headed out into the backyards of Cramer Hill. John Pilarchik, the local cobbler, was working behind the counter when Unruh entered his store through the back door. Without saying a word, he shot Pilarchik in the chest. Pilarchik fell to the floor with a surprised look on his face. Unruh then fired a second bullet through his head. He had just crossed the first name off his list. Unruh’s next port of call was the nearby barbershop, where his target, Clark Hoover, worked. It was at this point that things became truly gruesome. Hoover was cutting the hair of six-year-old Orris Smith, who was due back at school the next day. Smith was sitting on a white rocking horse when Unruh walked in. The gunman shot the kid right through the head, staining the horse’s flanks a horrific red. As Smith’s mother screamed, Unruh gunned down the barber and then stalked back out into the street. For some reason, he’d chosen to execute a defenseless child. It was the first sign that Unruh’s walk was moving beyond mere revenge and into much darker territory.

7 The Killings Turn Random

The moment Unruh stepped out the barbershop was when his walk finally metamorphosed into a modern mass shooting. From a targeted list, the attacks became suddenly random. A boy watching out a nearby window only just missed having his head blown off when Unruh fired a shot at him. Across the street, bar owner Frank Engel was nearly hit when the gunman unloaded a few rounds through the door of his business. Engel and Unruh had never spoken in their lives. Although Unruh still had one major target left on his list—the Cohens—his killings after them would all be entirely random. Combat veteran Alvin Day, 24 years old, slowed down as Unruh crossed the street, only for the gunman to shoot him dead through his windshield. Helen Wilson and her mother, Emma Matlack, were killed waiting at a red light, while Wilson’s nine-year old son, John, caught a bullet through the neck. The saddest of all these pointless murders may have been Thomas Hamilton’s. Just two years old, Thomas heard the gunshots and tottered over to the window to see what was happening. Unruh shot him clean through the face. The toddler died instantly.

6 Killing The Cohens

Before gunning down Alvin Day, Unruh made the last significant stop on his list—the drugstore owned by the Cohens. In his mind, these were the people who had made his life Hell on Earth. They’d torn down his precious fence. They’d spread rumors about his homosexuality (or so Unruh believed). And he was going to make them pay. Despite finding themselves at the eye of a storm of blood and madness, the Cohens managed some acts of astounding bravery. As Unruh killed a customer, James Hutton, in their doorway, Rose Cohen grabbed her 12-year-old son, Charles, and ran upstairs. As Unruh’s feet pounded on the steps, she hid her boy in a closet and then hid herself in a separate one. Her actions likely saved the young boy’s life. After Unruh shot in her hiding place, he apparently didn’t think to look in the other closet. By keeping her son separate from her, Rose had ensured that he lived. Others in the house were not so lucky. Rose’s mother, Minnie, was shot trying to call the police. Rose’s husband, Maurice, who Unruh thought had removed his fence, was shot trying to escape down the porch. The force of the bullet sent him flying into the street. Unruh’s work was almost done. He would kill one last victim, Helga Zegrino, who worked next-door to the Cohens. Unruh shot her as she was on her knees, begging for her life. It was a horrific, terrible moment. It also marked the point when Unruh’s rampage began to turn increasingly surreal.

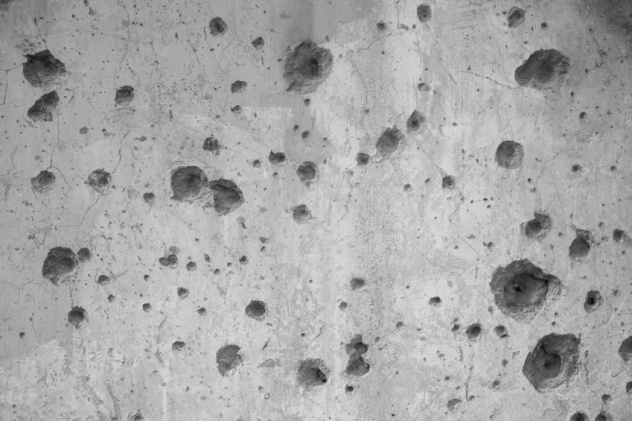

5 Things Get Really Crazy

For police responding to a mass shooting today, there are endless procedures to follow, ingrained by months and months of training. In 1949, none of that existed. So when the cops turned up to find Unruh fleeing back inside his apartment, they went for what seemed like the safest option. The building was surrounded by 50 officers with pistols, shotguns and machine guns. They opened fire. Years later, Patrick Sauer of Smithsonian Magazine estimated that around 1,000 civilians were in the line of fire that day, many of them simply milling around outside the apartment. Incredibly, with all the bullets pounding the building, no one got hurt. Unfortunately, that “no one” included Unruh. Despite having hundreds of rounds fired at him, Unruh managed to keep firing back, not sustaining a single injury. Meanwhile, a world away, Philip Buxton of The Camden Evening Courier was just receiving the first reports of the shoot-out. For some reason, he decided to look up Unruh’s number in the phone book and give him a call. Incredibly, Unruh answered. As bullets whizzed through the air, Unruh and Buxton had a short, strangely civilized conversation about the killings. When Buxton asked how many he’d killed, the gunman said that he didn’t know but proudly added that “it looks like a pretty good score.” When the reporter asked why he was killing his neighbors, Unruh seemed taken aback. “I don’t know,” he replied. “I can’t answer that yet. I’ll have to talk to you later. I’m too busy now.” And he hung up. At that point, a cop finally hurled tear gas into the apartment and smoked Unruh out. With a call of “I’m surrendering,” America’s first mass shooter stepped out the door and into history.

4 ‘Schizophrenia’

In the immediate aftermath of the killings, Howard Unruh’s first words were, “I’m no psycho, I have a good mind.” In light of what happened next, those words would take on a grimly ironic sheen. Although Unruh thought himself to be sane and provided clinical details of his crimes to investigating officers, no one at the time thought that a mass killer could be anything but a maniac. The day after his arrest, he was transferred to the Trenton Psychiatric Hospital for the Criminally Insane. Locked away in its calm and peaceful grounds, the man who had just murdered 13 people would never be sentenced. Instead, a group of doctors pronounced Unruh a paranoid schizophrenic, incapable of standing trial. In his Smithsonian Magazine article, Sauer argued that this was almost certainly a misdiagnosis. Unruh didn’t have any of the symptoms of schizophrenia; he was simply an angry, probably psychotic, man who decided to kill his neighbors. Were his case to have come up in the modern age, he would almost certainly have been deemed fit to stand trial. Even Unruh himself claimed that he should get the chair. But 1949 wasn’t the modern age. The first modern mass shooter in US history made a terrible fit for the mentality of the postwar generation, so they simply forgot about him. Unruh spent the rest of his life attending art classes and pottering around at Trenton Psychiatric Hospital. Not once in his remaining 60 years of life did anyone think to bring him to trial. Despite murdering 13 innocent people, Unruh was never convicted of anything.

3 Publicity

Although he wasn’t convicted, Unruh wasn’t silent about his experiences. He flatly told doctors and police everything they wanted to know about his crimes, sometimes in sickening detail. He also supplied possible clues to his past. He claimed that he’d once climbed into bed with his mother and fondled her breasts, their genitals pressed against each other. While it’s unknown if these “confessions” were true, they were certainly sensational. Add to that Unruh’s sensational crime, and his case became a lightning rod for publicity. It’s this final element that really makes Unruh’s Walk of Death different from everything that had come before. Previous US mass shootings had merely been crimes and were soon forgotten. But there was something about this case that proved different. It latched on in the psyches of both the public and unbalanced people everywhere. The New York Times covered it in a Pulitzer Prize–winning article. People across the country pored over every detail of the terrifying, perplexing case. Unruh became the first celebrity mass shooter. It was a watershed moment that would usher in everything that came after it.

2 The Final Twist Of The Knife

When writing the story of any mass shooting, it’s all too easy to forget about the victims. They become peripheral characters in a larger drama about an angry person with a gun and a grudge. Charles Cohen’s whole life became exactly that. At 12 years old, he’d hid in a darkened closet, forced to listen as a madman murdered his entire family. For his remaining 60 years on Earth, his life would be tied inextricably to Howard Unruh’s. The cruelest part of Cohen’s life was that Unruh hadn’t died in his rampage. While most mass shooters commit suicide or are gunned down, Unruh had lived. Not only that, he’d never been charged. As time passed, Charles Cohen’s whole world began to revolve around seeing the back of the man who had murdered his parents. In 1999, he told The Philadelphia Inquirer that he was forever waiting for the phone call that would tell him his tormentor had died. “I’ll make my final statement and I’ll spit on his grave and go on with my life,” he said. Fate, sadly, had other plans. In a final, sickening twist of fate, Charles didn’t live long enough to see Unruh buried. He died of a stroke aged 72 in September 2009. Perversely, Howard Unruh passed away only one month later. It was almost as if the killer was having one last sadistic laugh at his survivor’s expense. In all his long life, Charles Cohen was never free of Unruh’s shadow.

1 A Dark Legacy

Since 1949, the US has grown sadly accustomed to mass shootings. Almost two decades after Howard Unruh gunned down his neighbors in Cramer Hill, Charles Whitman would climb a tower at Texas University and shoot 16 strangers dead with a sniper rifle. By that point, Unruh’s story had faded into history. After Whitman’s mass shooting, those who wanted to kill strangers were more likely to be influenced by the former sniper than the unhinged mommy’s boy. But Unruh remains important because he was the first and also because his actions had no reason behind them. At his autopsy, Whitman was revealed to have a brain tumor that badly affected his ability to feel and perceive emotion. Unruh, by contrast, was angry about a fence. Today, we can probably all name enough “celebrity” mass shooters to at least fill the fingers of one hand. Every month seems to bring reports of new atrocities being committed and innocent people dying. Even without Unruh, this would probably be the case. Yet this sad and lonely man still left behind a poisonous legacy. He was the first person to deal with alienation like a true modern psychopath. In doing so, he pointed the way for all the psychopaths who came after him. Unruh may have only personally fired enough bullets to kill 13 people, but his gunshots echoed throughout modern US history.